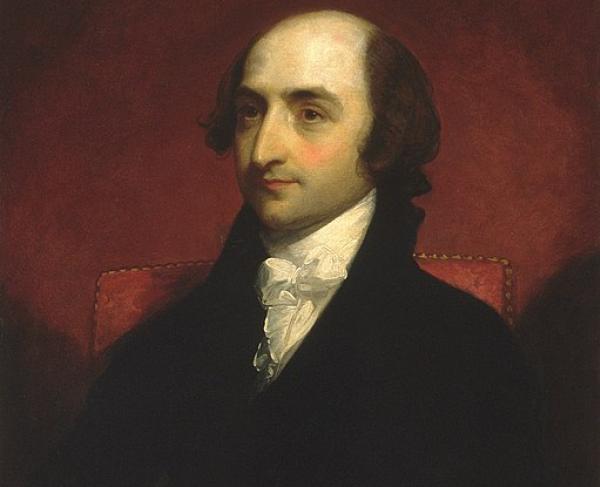

Henry Dearborn

Born in the New Hampshire Colony to one of the oldest families in New England, Henry Dearborn grew up privileged, well-educated and was beginning a career as a doctor when the Thirteen Colonies declared independence from Great Britain. A firm Patriot, Dearborn helped form his own local militia after Lexington and Concord, and marched his command all the way to Massachusetts to join the fledgling Continental Army. He immediately scoffed at the apparent lack of professionalism among the ranks as well as the officers, particularly noticing the lack of uniforms and the fact that the officers were on foot. Nevertheless, Dearborn and his men went on to fight in some of the most important battles of the war, including Bunker Hill, Quebec (where he was briefly captured), Saratoga, Monmouth and Yorktown. Throughout the war, he recorded his thoughts and opinions in series of private journals later published in six volumes. He also received at least two promotions during the war, starting out as a captain of militia, and serving as colonel by the war’s end. After his discharge, he began a successful political career, serving as U.S. Representative for Massachusetts, and Secretary of War under President Thomas Jefferson.

When the War of 1812 began, Dearborn reentered military service on the request of President James Madison. Although promoted to Major General, and overall command of troops in the Northeast, Dearborn proved himself far from the successful soldier he once was. His command coincided with the failed invasion of Canada, as well as the loss of Fort Niagara and control of Lake Ontario. After less than a year in command, Dearborn was transferred, and served the rest of the war in Boston, performing mostly administrative duties.

After the war, he caused a major controversy when he accused his long-deceased commander at Bunker Hill, Israel Putnam, of cowardice and incompetence in the face of the British attack there. Dearborn’s account of the battle backfired, as Putnam had long been lionized as a hero of the Revolution, and the ensuing controversy ruined his reputation amongst New Englanders, dashing any further political ambitions. He ran for the governorship of Massachusetts, but lost, and his re-nomination to the Cabinet was rejected by the Senate for his mediocre record in the recent war. His served his last official government position as Minister to Portugal from 1822-1824, after which he went into retirement. He died five years later in his home, and was buried in the Forest Hills Cemetery of Boston.