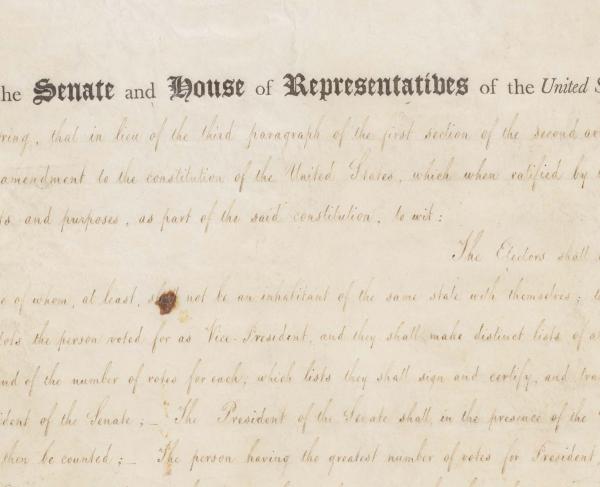

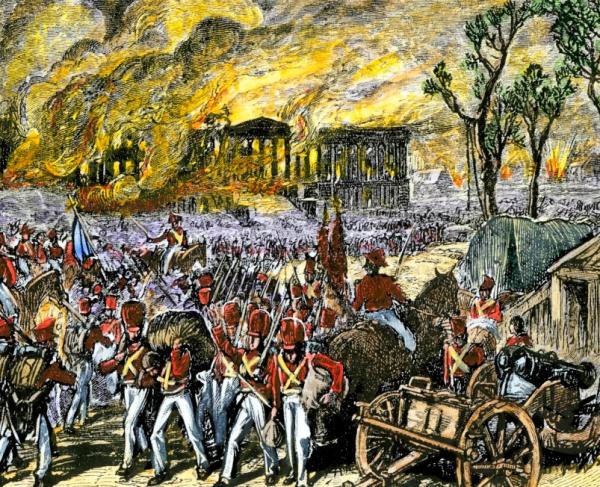

For as famous as it is, the so-called Star-Spangled Banner is shrouded in plenty of misconceptions. Perhaps most important is this: The massive relic on display in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History is NOT the flag that flew over Fort McHenry while it was under British attack. Given the foul weather during the bombardment, the fort instead flew its smaller storm flag, raising the massive version when the British disengaged the following morning.

In the terminology of the time, as national flags, both emblems would have been termed “ensigns”; as an especially oversized version, the larger one was a “garrison flag.” In fact, before it received its more poetic moniker, Fort McHenry’s example was known as the “Great Garrison Flag.”

Both flags that figure into the Battle of Baltimore were ordered by the fort’s commandant in the summer of 1813. Although only newly arrived from the war at the Canadian frontier, Major George Armistead was confident that the British forces would turn their might toward Baltimore and wrote to his superiors that it was “my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance.”

The commission to make the banners went to a well-respected Baltimore flag maker named Mary Young Pickersgill, who had undertaken other smaller projects set by the U.S. Army and Navy. Over the course of six weeks, 37-year-old Pickersgill worked with her daughter, Caroline; two teenage nieces, Eliza and Margaret Young; an indentured African American apprentice, Grace Wisher, and her own mother Rebecca Young, who had taught her the art of flag making, plus additional hired seamstresses as necessary. The dimensions of the Great Garrison Flag dwarfed the home that Pickersgill rented, so to have enough workspace, the women negotiated use of the nearby Claggett’s Brewery late into the evening after the day’s production had ceased. For their labors, they were ultimately paid $405.90 for the Great Garrison Flag and $168.54 for the storm flag — about $9,200 dollars adjusted for inflation.

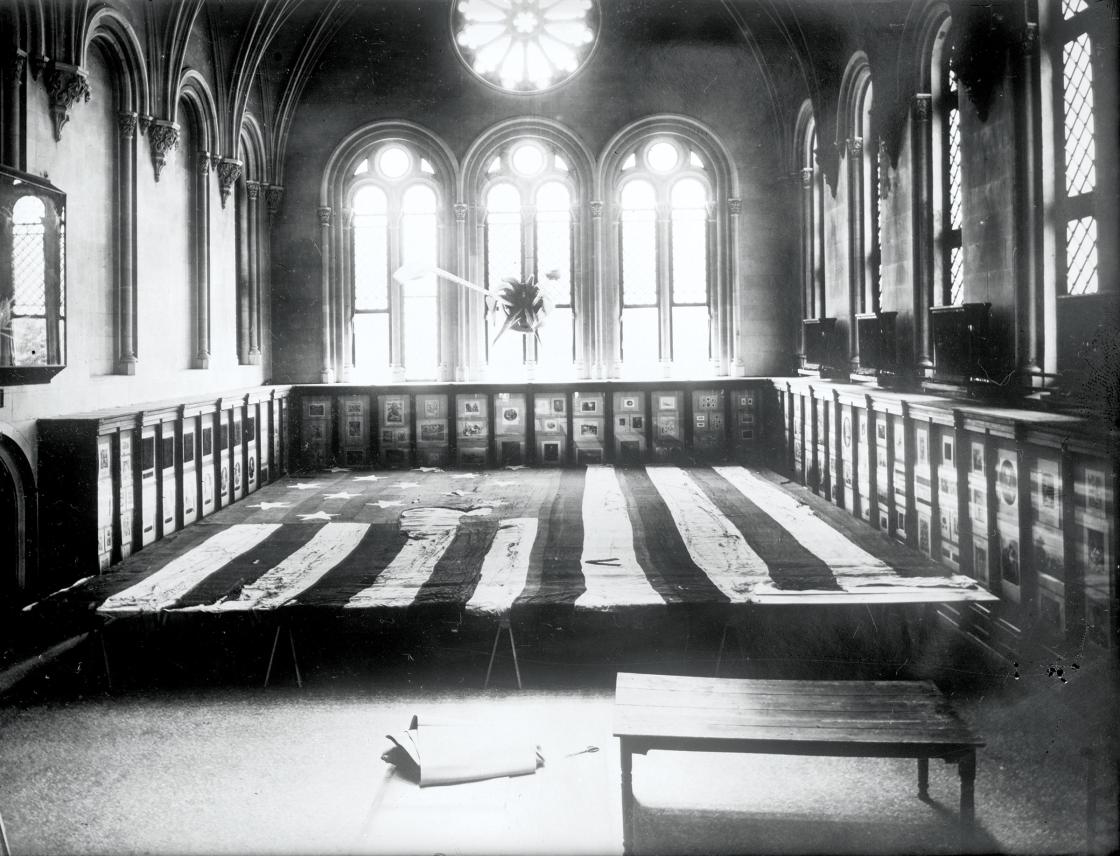

Just how big was the flag flying over Fort McHenry at dawn on September 14, 1814? It measured 30 by 42 feet, making it reportedly the largest flag flown in combat up to that time. Each of the 15 red and white stripes measured two feet across (until 1818, a star and a stripe were added for each state that joined the Union), as do the 15 stars, arrayed in five offset rows. The whole project took about 400 yards of fabric (English wool bunting for the stripes and blue canton, white cotton for the stars) and weighed more than 50 pounds. It took 11 men to hoist the Great Garrison Flag to the top of its 90-foot pole.

After the war, the flag passed into the possession of the Armistead family, where it stayed for around 90 years, occasionally displayed for patriotic gatherings. During this time, as was typical before any formal regulations for treatment of the national flag were adopted, pieces of the ensign were clipped off to use as gifts. Increasingly concerned about the flag’s fragility, in 1907 Armistead’s grandson Eben Appleton loaned the Star-Spangled Banner to the Smithsonian Institution, making it an outright gift five years later. In 1914, the Smithsonian began a massive restoration, as legendary embroiderer Amelia Fowler and a team of assistants applied 1.7 million patented honeycomb stitches to mount the flag to a linen backing.

Over the ensuing century, the science of material conservation has evolved considerably (from attempting to replicate its original appearance to ensuring its long-term stability), and the flag has gone through multiple evolutions of display. Determined to keep the relic on display without compromising its integrity unnecessarily, in 1996, the Smithsonian began preparations to give the flag a full conservation treatment. The multimillion-dollar project began in 1998, and museum visitors were able to watch the painstaking work of undoing previous, well-intentioned repairs — even today, there remain 37 visible patches — through a massive window. Specialized techniques were used to clean and stabilize the flag, and to protect it as the surrounding museum underwent its own renovation. The Smithsonian eventually welcomed visitors to see the flag “what so proudly we hailed” in 2008, when the revitalized museum reopened.