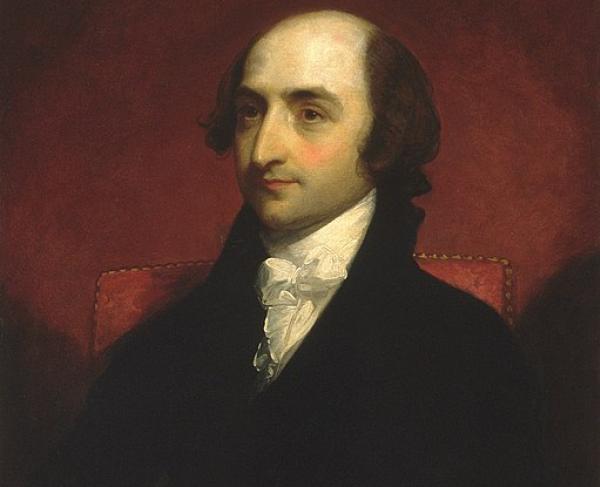

William Hull

Despite his decades of service, William Hull’s contemporaries held his record in low esteem, partially due to one particular moment in the War of 1812 that blemished his entire career. Born in the Connecticut Colony in 1753, Hull was a good friend of fellow Yale graduate Nathan Hale, the patriot spy and eventual State Hero of Connecticut. Hull was responsible for publicizing Hale’s heroism after his execution by the British. Hull himself, as an educated man, also served as an officer in the Continental Army, and saw action at White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Saratoga, and Monmouth. As a major, he managed to secure compliments from multiple superior officers for his conduct. He resigned from the army as a lieutenant-colonel, and like many of his peers, he entered politics after moving to Massachusetts after the war. In addition, Hull was elected captain of the oldest military organization in North America, the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts.

Hull’s comfortable career path in Massachusetts came to an abrupt end when President Thomas Jefferson appointed him first Governor of the Michigan Territory in 1805. As governor, his main responsibility was to acquire land from local Native American tribes for further settlement. His efforts were mostly peaceful, and he successfully negotiated the Treaty of Detroit, which annexed the lands around modern-day Toledo, Ohio from the Wyandot and Potawatomi nations. But rapid settlement provoked resentment from many Indian locals, especially followers of the prophet Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh. Facing pressure from increased Indian resistance, who had recently allied with the British, Hull reluctantly accepted a commission as Brigadier General just in time for the War of 1812. The sixty-year-old general led part of the Invasion of Canada at the head of the Ohio militia. Unfortunately for Hull, the campaign was hastily planned and poorly executed. From the onset, his men were ill-equipped and disciplined, and many of their supplies, as well as Hull’s planned movements, were captured by the British. The Governor’s progress stalled at Amherstburg, and deciding he lacked sufficient artillery and naval support to take the nearby British fort; he retreated to Detroit. That is where he made the worst mistake of his career. Tecumseh and General Issac Brock besieged the fort at Detroit, utilizing a small force of British regulars, Canadian militia, and Native Americans. Though Hull outnumbered the enemy by a wide margin, both Brock and Tecumseh employed numerous ploys to make him think the opposite was true. Their tactics worked, Hull lost his nerve, and he surrendered the fort on the 16th of August, 1812. Hull and his family later claimed he merely feared for the women and children trapped inside the fort and was carrying out his duty to protect them by surrendering. His explanation fell on deaf ears, as he was court-martialed for his conduct and sentenced to death before a pardon from President Madison saved his life. The British, meanwhile, held on to Detroit for a year before their defeat on Lake Erie.

Understandably tired of politics, Hull retired to his home in Massachusetts, where he maintained positive relationships with several other veterans of the Revolution, including the Marquis de Lafayette, who visited Hull during his tour of the United States. His son, Abraham, also fought in the War of 1812 but perished in the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. His nephew, whom William also raised, was Isaac Hull, was an American naval hero who captained the USS Constitution during the war. William Hull spent most of his life in retirement publishing his memoirs to clear his name before dying on November 29, 1825. His descendants continued that task well after he passed.