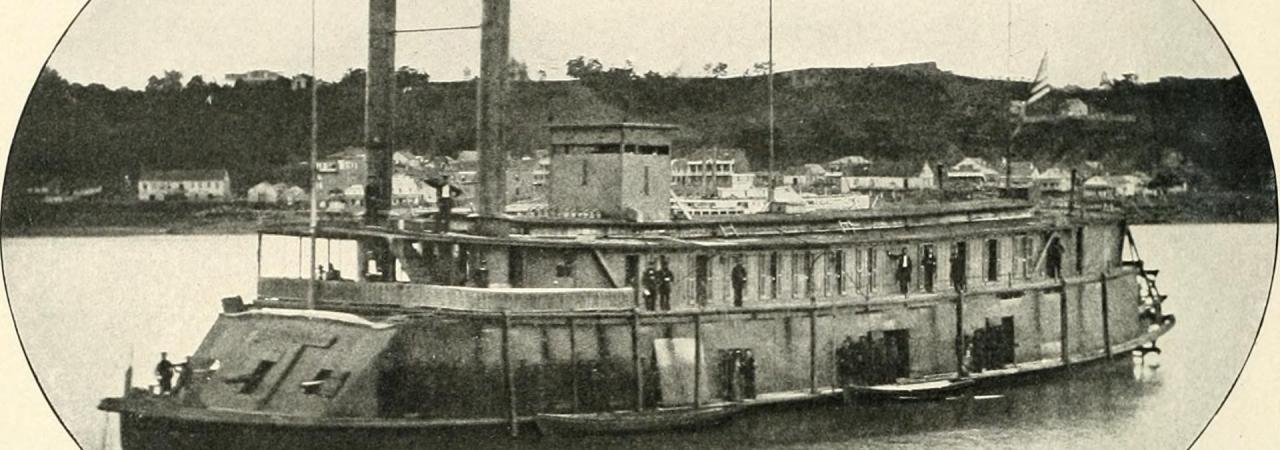

The USS Rattler was the flagship of the Mississippi Squadron's "tinclad" flotilla, the name given to civilian river steamers repurposed by the Navy.

Arkansas Post (1863)

Fort Hindman

Gillett, AR | Jan 9 - 11, 1863

The Battle of Arkansas Post, also known as the Battle of Fort Hindman, was a combined land-river assault by Union forces on the Confederate Fort Hindman, which loomed over a bend in the Arkansas River near the town of Arkansas Post. As the Union advance down the Mississippi River passed the mouth of the Arkansas, the presence of Fort Hindman outflanked the Federal forward positions.

Confederate ships used the Fort as a base to launch vexing raids on Northern shipping, culminating in the embarrassing capture of the Blue Wing, a supply ship laden with munitions meant for general William T. Sherman’s command. To intensify the problem, throughout the final months of 1862 rumors abounded that a powerful new ironclad was being built at Little Rock.

In the midst of organizing for an attack on Vicksburg, Mississippi, Union commanders decided to deal with the threat in their rear in the first week of 1863. River gunboats pounded the fort as the infantry made a slogging assault overland. Outnumbered and outgunned, nearly 5,000 Confederates, approximately one-fourth of the Confederate force in Arkansas, surrendered on January 11, 1863. This was a catastrophic capture, not to be equaled west of the Mississippi River until general Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the remainder of the department, some 20,000 men, on June 2, 1865 in Galveston, Texas.

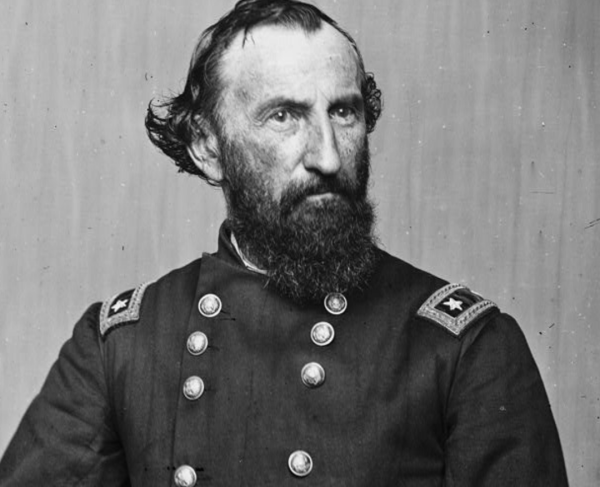

General William T. Sherman had met a bloody repulse at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou in December, 1862, and was temporarily relieved of his command. He was superseded by general John McClernand, a political officer who was almost universally despised in regular Army circles. Sherman later called the replacement “the severest test of my patriotism.”

McClernand was under orders from Ulysses S. Grant to push down the Mississippi and open an assault on the river fortress of Vicksburg. An attack on Fort Hindman was not part of his purview. Nevertheless, he grew enthusiastic about the idea after Sherman recommended such a move, allocating 10,000 men to an expedition and requesting gunboat support from fleet commander David D. Porter. Porter, however, loathed McClernand and refused to provide support unless Sherman led the infantry assault himself. Additionally, Porter insisted on personal command of the support flotilla. Thus a 10,000-man operation became a 33,000-man operation, supported by fifty transports and nine gunboats (Baron DeKalb, Cincinnati, Louisville, Glide, Rattler, Black Hawk, Lexington, Monarch, and New Era) and the whole affair personally planned and led by the three top commanders in the theater.

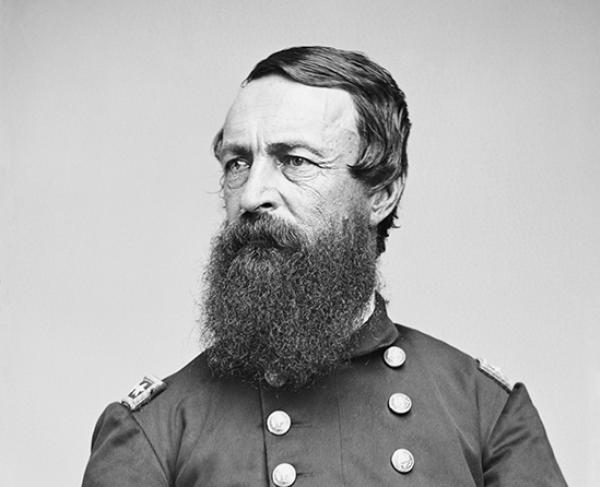

The defense of Arkansas Post fell to Confederate general Thomas Churchill, a talented commander who had directed a devastating flank attack at the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky the year before. He now led a force of some 5,000 men, mostly dismounted Texas cavalry. Fort Hindman was strongly built, and Churchill further augmented the defenses with rifle pits and trenches on land and log pilings and range targets in the river.

The Union flotilla steamed into staging areas a few miles away from the fort on the evening of January 9. The gargantuan attacking force finally completed its debarkation the next morning under the eyes of Churchill’s scouts. The size of the Union expedition was most unexpected. Upon receiving the report, Churchill urgently wired theater commander Theophilus Holmes to ask for instructions. Holmes wired back “to hold out until help arrived or until all were dead.”

Holmes’s order was strange, considering he made no provision to reinforce Churchill’s garrison. When the Union attack got underway on January 10, Churchill and his eleven regiments were facing very long odds.

From rifle pits cut into the slopes of Coines’s Hill, Confederate vedettes could see the sinuous Union assault columns winding their way along the riverbank. In the river, ironclads belched steam as they moved on the infantry’s flank. Huge gunboat shells began to howl into the trenches as the Navy laid down a punishing cover fire for the deploying infantry. Outflanked on the water, the Confederates retreated through the mud back towards the fort as the Union lines began to slog up the hill.

McClernand, relying on reports relayed to him from a private soldier who had climbed a tall tree, soon sent word to Porter that the infantry assault was in place. The tree-climber, however, had failed to notice that half of the army, Sherman’s corps, was caught in the mire and well behind schedule.

The gunboats went in alone, dashing to within 400 yards of the fort and opening a furious cannonade. The Rattler, a tinclad, crashed aground in Churchill’s log piles and was torn apart by the Confederate guns. The other Union ships also took a bruising, although Porter claimed that many shells were deflected by tallow that the sailors had rubbed over their ships’ hulls before the fight. After a firefight lasting several hours, Porter’s ships withdrew. There was no further infantry attack that day, but Fort Hindman’s walls were crumbling after sustaining hundreds of blows from the Union naval guns, which fired shells ranging from 30-105 pounds.

The Union force renewed the assault shortly after noon on January 11. The Confederate infantry put up a stubborn fight and drove the attackers to ground with musketry as they tried to advance across scrubby cleared fields. But Fort Hindman itself could no longer withstand the naval bombardment. Walls tumbled down and, one by one, guns flickered out of action. Their passage no longer hindered, the gunboats steamed past the ruins and trained their guns on the Confederate trenches. The first white flag came up at 4 P.M., hoisted by men of Colonel John Garland’s brigade on the Confederate left flank.

The end of the battle came with some confusion. Porter himself was the first to climb into a hole in the fort’s wall and secured the surrender of Colonel John Dunnington, the officer in charge of the fort’s artillery. Out in the scrubby field, Sherman found General Churchill and demanded his surrender. At that moment Colonel Garland approached, and Churchill began to angrily reprimand him for surrendering without orders. Garland hotly protested that he had been ordered to surrender, presumably by a member of Churchill’s staff. Colonel James Deshler, commanding the Confederate right flank, then arrived and proclaimed that he had not surrendered at all and would continue the fight. He acquiesced when Sherman, in some irritation, pointed out that his men were already in the process of disarming Deshler’s troopers.

By the end of the day, more than 4,700 Confederates were captured. Even though the Southern infantry fought well, inflicting more than a thousand casualties while suffering approximately seven hundred, there could only be scant defense against the combined-arms tactics that the Union Army and Navy had employed at Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, and Island Number Ten in the months before the battle for Fort Hindman.

With the fort razed and the Arkansas River open, McClernand ordered a raid on Little Rock to commence before nightfall. Fort Hindman had represented the only real challenge to the Union naval power on the river. The rumors of the Little Rock ironclad were false. The Confederate fleet on the river was burned to prevent its capture.

Despite the success of the operation, Grant was exasperated by the loss of time, resources, and men on a maneuver that contradicted his orders. The immensely self-serving after-action reports submitted by McClernand and Porter (each of whom barely mentioned the other’s contributions) were also stirring up fresh enmity in the army’s high command. On January 30, 1863, Grant steamed down from Memphis, Tennessee to replace McClernand as chief general in the field. By securing the Union right flank and inducing Grant to take personal command, the Battle of Arkansas Post marked a turning point in the campaign for Vicksburg.

Arkansas Post (1863): Featured Resources

Related Battles

30,000

5,000

1,092

4,931