Andersonville: The Deadly Confederate Prison Camp

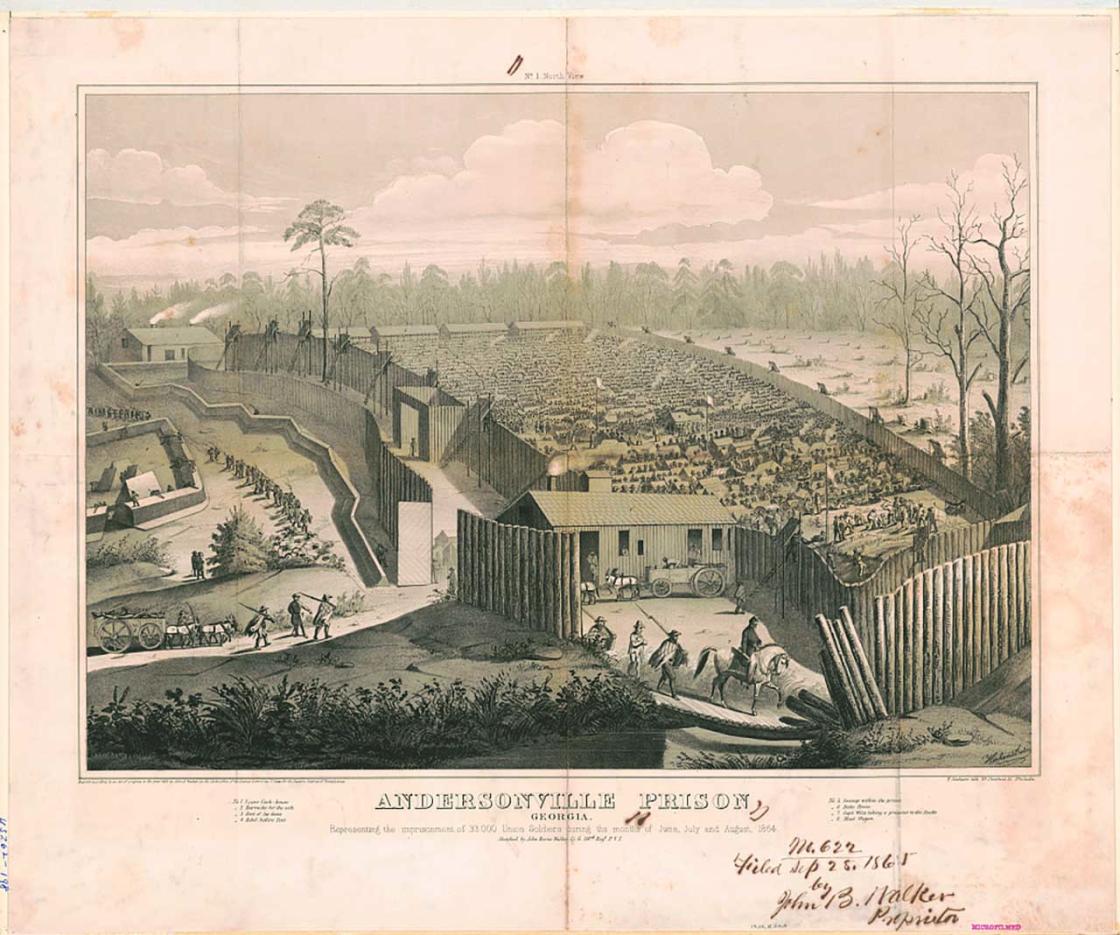

Andersonville, or Camp Sumter as it was known officially, held more prisoners at any given time than any of the other Confederate military prisons. It was built in early 1864 after Confederate officials decided to move the large number of Federal prisoners in and around Richmond to a place of greater security and more abundant food. During the 14 months it existed, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined here. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure to the elements.

The prison pen was surrounded by a stockade of hewed pine logs that varied in height from 15 to 17 feet. The pen was enlarged in late June 1864 to enclose 261/2 acres. Sentry boxes—called “pigeon roosts” by the prisoners—stood at 90-foot intervals along the top of the stockade and there were two entrances on the west side. Inside, about 19 feet from the wall, was the “deadline,” which prisoners were forbidden to cross. The “deadline” was intended to prevent prisoners from climbing over the stockade or from tunneling under it. It was marked by a simple post and rail fence and guards had orders to shoot any prisoner who crossed the fence, or even reached over it. A branch of Sweetwater Creek, called Stockade Branch, flowed through the prison yard and was the only source of water for most of the prison.

In an emergency, eight small earthen forts around the outside of the prison could hold artillery to put down disturbances within the compound and to defend against Union cavalry attacks.

The first prisoners were brought to Andersonville in late February 1864. During the next few months, approximately 400 more arrived each day. By the end of June, 26,000 men were penned in an area originally meant for only 10,000 prisoners. The largest number held at any one time was more than 33,000 in August 1864. The Confederate government could not provide adequate housing, food, clothing or medical care to their Federal captives because of deteriorating economic conditions in the South, a poor transportation system, and the desperate need of the Confederate army for food and supplies.

These conditions, along with a breakdown of the prisoner exchange system between the North and the South, created much suffering and a high mortality rate. “There is so much filth about the camp that it is terrible trying to live here,” one prisoner, Michigan cavalryman John Ransom, confided to his diary. “With sunken eyes, blackened countenances from pitch pine smoke, rags, and disease, the men look sickening. The air reeks with nastiness.” Still another recalled, “Since the day I was born, I never saw such misery.”

When General William T. Sherman’s Union forces occupied Atlanta, Georgia on September 2, 1864, bringing Federal cavalry columns within easy striking distance of Andersonville, Confederate authorities moved most of the prisoners to other camps in South Carolina and coastal Georgia. From then until April 1865, Andersonville was operated in a smaller capacity. When the War ended, Captain Henry Wirz, the prison’s commandant, was arrested and charged with conspiring with high Confederate officials to “impair and injure the health and destroy the lives…of Federal prisoners” and “murder in violation of the laws of war.” Such a conspiracy never existed, but public anger and indignation throughout the North over the conditions at Andersonville demanded appeasement. Tried and found guilty by a military tribunal, Wirz was hanged in Washington, D.C., on November 10, 1865. Wirz was the only person executed for war crimes during the Civil War.

Andersonville prison ceased to exist when the War ended in April 1865. Some former prisoners remained in Federal service, but most returned to the civilian occupations they had before the War. During July and August 1865, Clara Barton, along with a detachment of laborers and soldiers, and former prisoner Dorence Atwater, came to Andersonville cemetery to identify and mark the graves of the Union dead. As a prisoner at Andersonville, Atwater had been assigned to record the names of deceased Union soldiers for Confederate prison officials. Fearing loss of the death records at war's end, Atwater made his own copy of the register in hopes of notifying the relatives of the more than 12,000 dead interred at Andersonville. Thanks to Atwater’s list and the Confederate death records captured at the end of the War, only 460 of the Andersonville graves had to be marked “Unknown U.S. soldier.”

This article was adapted from National Park Service brochure "Andersonville."