“These are the times that try men’s souls,” wrote Thomas Paine in American Crisis on December 19, 1776. Paine’s immortal words perfectly sum up the state of the Revolution at the end of 1776. The crisis was simple; George Washington’s army had been beaten and driven from Long Island, New York which was now in British hands, and many of his troop’s enlistments would expire at the end of the year. After a long retreat across New Jersey, the only thing holding the British at bay was winter, and the Delaware River. The Revolution tottered on the brink of failure.

The Continental Army arrived on the New Jersey bank of the Delaware River on December 2, 1776. For five days, Washington ferried his troops over to Pennsylvania, working round the clock to save his men and supplies. The British arrived in Trenton on the eighth, and were content to let the rebels slip away. Even if they were inclined to continue the pursuit, Washington had ordered anything that could be used as a boat be removed to Pennsylvania or destroyed.

The British, after chasing Washington across New Jersey, retired and formed an “extended chain” of winter garrisons, as they consolidated their gains and waited for winter. They preferred this path rather than risk than British lives in an attempt to destroy the rebellion. The “chain” consisted of seventeen fortified towns along the supply route from the Delaware River to the British stronghold at Staten Island.

The British commander, William Howe, had made a miscalculation, however, and overextended his forces. Howe was attempting to monitor the Continental Army across the Delaware, secure his supplies, and suppress patriot sentiments in the colony, all while protecting loyalists. The British quickly realized the sheer size of the American colonies. Howe’s “extended chain” would only hold five percent of New Jersey, and stretched British resources to their limit.

At the end of the chain, most exposed to the Continental Army, were the garrisons at Burlington, Bordentown, and Trenton. Howe placed his German troops in these garrisons, which did not sit well with his German subordinates.

Washington needed a miracle. The Continental Army needed to hold together long enough to win a victory and reverse the course of the war. Morale was at an all-time low, Congress had abandoned Philadelphia, and many of Washington’s 5,000 men would end their term of enlistment at the end of the year.

Washington turned to his friend Thomas Paine to help bolster morale. Paine, who had followed the army on campaign and suffered alongside the soldiers, was popular with the troops. When American Crisis I began circulating at the end of the December, it reinvigorated Washington’s army. Paine followed his immortal opening with a direct plea to the men saying, “The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.” Washington’s army stood firm.

With the crisis of troops and supplies abating, Washington turned his focus on a daring strike at the overextended British garrisons. Preparing his forces would take time, and in the meantime, he ordered the New Jersey militia to cause havoc along the British supply lines. Many New Jersey militiamen went beyond Washington’s orders as frustrations at the British occupation spilled into the roads and fields of New Jersey. By the middle of December, Colonel Johann Rall, commanding the garrison at Trenton, was forced to send his dispatches to Princeton with a guard of one-hundred men, and sometimes a light field gun.

On December 22, Washington began to lay out his strategy for an attack on a British garrison. Reinforcements had arrived from New England, morale had improved, and supplies had trickled into the American camp. Some of his officers advocated caution and to save the army for the spring campaign, others encouraged an attack. On Christmas Eve a council of war was called, Washington had made his decision; the target would be Trenton.

Washington’s plan of attack was equal parts daring and desperation, he would gamble his army in exchange for a victory. Only a victory would save the revolution. The Continental Army would attack Trenton with overwhelming force, surrounding the town while overpowering the garrison with superior numbers in both men and artillery. The biggest obstacles to overcome was the ice choked river, and the worsening weather.

The sporadic attacks by New Jersey militia that December had an added effect beyond harassing British supply: exhaustion. There would be no Christmas celebration for the Hessian garrison at Trenton. Constant threat from the Hunterdon County militia resulted in Colonel Rall keeping a portion of his garrison dressed and equipped at all times, including throughout the night. Alarms on the 22, 23, and 25 of December turned out the entire garrison. Combined with losses suffered in New York, Rall’s brigade was ragged and exhausted.

Washington decided to forgo traditional military doctrine and divide his forces. About 2,000 men under Colonel John Cadwalader would cross the river south of Trenton to pin the Hessian forces at Burlington and Bordentown, removing the potential for any reinforcements. General James Ewing would take about 800 men and cross at the town itself, with their objective being the Assunpink Creek Bridge on the south side of town, cutting the major line of retreat.

Washington, with the main body of about 2,400, would cross nine miles north of Trenton and make a two-prong attack on the town from the north. With the orders issued, Washington’s force set out on Christmas Day, intending to cross overnight and attack the next day. The watchword for the operation: “Victory or Death.”

As Washington’s force gathered, the weather began to worsen. Ice jams choked the southern river, where the tide stacked up the ice into an impenetrable wall that could not be crossed on foot or by boat. Ewing’s force was unable to attempt the crossing, while Cadwalader managed to get a few men across further south before being turned back. The outlook looked bleak before a shot was fired.

Farther North, at the main crossing site of McKonkey’s and Johnson’s ferries, Henry Knox, in charge of the logistics of the crossing, had a growing problem. The weather was worsening; a Nor’easter was blowing in, bringing freezing rain, sleet, and snow. Most of the army’s artillery was crossing with Washington, and these guns added to Knox’s woes, but he was determined to not lose a single one of his precious cannon. Ice floes added to the misery on the river, these chunks of skim ice impeded the boats, and pushed them further downstream with the current. By the time 2,400 soaked and freezing men and eighteen cannon had crossed, it was 3 AM; the army would not be ready to move until 4 AM.

Washington hoped to reach the outskirts of Trenton before dawn to maintain the element of surprise; with almost ten miles to march and the weather only getting worse, the original timeline was impossible. Washington called a council of war in order to decide whether the army should abandon the attack and recross the river, or continue as planned.

The attack would continue, despite the risks. About halfway through the march to Trenton, Washington again divided his army. Half, under General John Sullivan, would march close to the river while the main body under General Nathanael Greene would take the inland route and cut the King’s Highway leading into town. Both columns arriving simultaneously was critical.

While the storm began to abate overnight, the weather provided yet another concern: wet gunpowder. When General Sullivan sent a courier warning Washington of his men’s damp powder, Washington replied “Tell General Sullivan to use the bayonet. I am resolved to take Trenton.” Two miles outside of town, the advance parties of both columns attacked.

That same morning a force of fifty Virginia Continentals had attacked a Hessian outpost, not knowing about the plan to attack the town. While Washington feared that this attack ruined the element of surprise, Colonel Rall mistook it for an impending attack uncovered by British intelligence, and was not expecting another attack in force.

At 8:00 AM Washington personally led an assault on a Hessian outpost, about a mile from the town. This started a fighting withdraw towards town. At about 9:00 AM the main attack on the town began. American artillery deployed on high ground north of town, at the “V” where King and Queen Streets intersected.

Initially the Hessians were able to make an organized retreat, using the houses to cover their withdraw. As more and more Hessian guard units engaged, it became apparent that the attack was not another raid, but the main American army. Outnumbered two-to-one the 1,200 Hessian soldiers were forced to give ground in order to maintain cohesion. Washington capitalized upon this opportunity, and directed his troops to cut the road towards Princeton, and the Hessian’s main escape route.

The Hessians were able to deploy and form ranks against the American onslaught. Realizing that the American’s controlled the vital intersection of King and Queen streets, and with artillery raining down on his men, Colonel Rall was determined to break the strongpoint. He ordered his own regiment to advance up King Street, with the Lossberg Regiment advancing up Queen Street, and the Knyphausen Regiment standing by as a reserve.

Rall’s plan quickly unraveled, as American artillery and musketry hammered his men. The Hessian artillery was quickly silenced by their American counterparts, with the guns captured by the advancing Americans. As the Rall and Lossberg Regiments began to break and flee to the east, the Knyphausen Regiment became separated and made an attempt to cross Assunpink Creek by the southern bridge. These men were cut off by a fast moving Brigade from Sullivan’s Division, but not before the small contingent of British cavalry and a few Hessians and noncombatants were able to cross.

Colonel Rall was able to rally the two regiments with him in the fields and orchards east of town. He ordered his men to attack the American left flank, yelling “Forward! Advance! Advance!” with the bands playing to bolster his men. Colonel Rall was struck in the side by a musket ball and mortally wounded. Washington saw this maneuver, and countered it by shifting his line. With American troops on three sides, and the Assunpink Creek behind them, the Rall and Lossberg Regiments surrendered. Minutes later, the Knyphausen Regiment also surrendered after failing to cross the bridge.

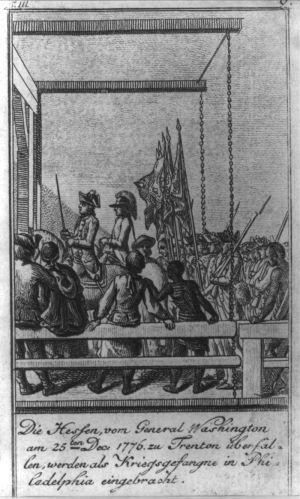

Hessian losses were 22 killed, 83 wounded, and about 800 captured. Also captured were large numbers of supplies, and the Hessian artillery. American losses numbered only five wounded, amongst them future President James Monroe.

Washington quickly learned, however, that Ewing and Cadwalader’s forces had not made the crossing. Fearing his position was too exposed, with too few men to make an attack on Princeton or New Brunswick, Washington decided to recross the Delaware with his prisoners and supplies. By noon on the 26th, Washington was safely across the river. The daring attack had been an overwhelming success, but it would only be the first chapter in a ten-day campaign that would change the course of the war.

Related Battles

5

905

75

270