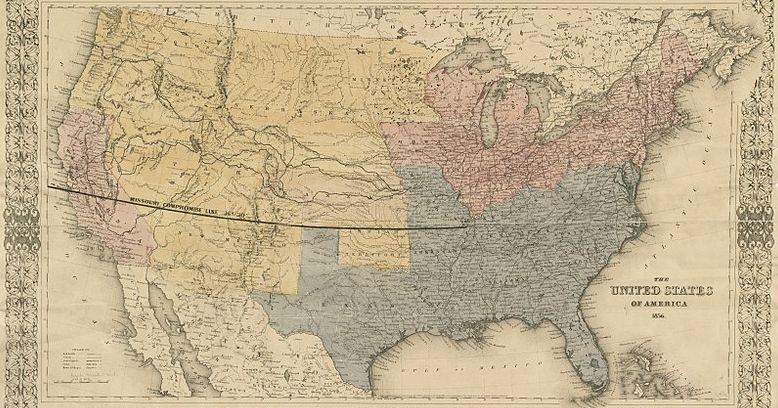

The Missouri Compromise

After reaffirming their independence from Great Britain with the War of 1812, Americans looked westward to new horizons. Yet, as the United States moved west, new challenges arose regarding slavery’s expansion to new territories, including the Northwest Territories and territories created through the Louisiana Purchase. The Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territories (Ohio, Indiana, Michigan Illinois, Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota); however, the debates over the organization Louisiana Purchase came to a head when Missouri applied for statehood in 1819. Although not the first American political compromise over slavery, the Missouri Compromise marked the beginning of an era where debates over slavery dominated the American political landscape.

In 1819, the Democratic-Republican Party had a monopoly over American politics as the Federalist Party ceased to exist following the War of 1812. However, factions existed within the Democratic-Republican Party which proved troublesome during Missouri’s bid for statehood. Representative James Tallmadge proposed as a condition of Missouri’s statehood that no further slaves could be imported into the state and all children born after Missouri’s admission to the Union shall be born free. This condition, known as the Tallmadge amendment, set out a plan for gradual emancipation in Missouri. Many northerners supported this amendment. However, one cannot equate northern support for this amendment with their support for emancipation and abolition. Many northerners were not abolitionists and in fact, by our modern standards, many held racist views on African Americans. Northerners mainly supported this amendment because they wanted to limit the political influence of southerners which was disproportionately large because of the three-fifths clause. Limiting slavery in the territories limited the representative boost gained from the three-fifths clause and denied southerners two extra Senate seats thereby limiting southern political influence.

While the Tallmadge amendment may seem reasonable to us today, in the antebellum era Americans (especially southerners) considered any political discussion of emancipation or abolition to be radical. In fact, southerners remained firmly opposed to any action that would limit the expansion of slavery in the territories. One reason was the commonly held belief that slavery needed to spread for it to survive. Tied into this belief was the fear of servile insurrection. Since many believed that if slavery could not expand westward, it would continue to grow on the east coast for a period, leaving a large concentration of slaves against a dwindling proportion of whites. Slaves would capitalize on their large population and engage in a large-scale revolt against their white masters inciting a horrifying race war. While this may seem farfetched, this scenario occurred during Haitian Rebellion in 1791, which remained on the forefront of southerners’ minds. Another reason why southerners supported slavery’s extension was for economic reasons. By 1820, human bodies served as the “cash crop” for Upper South states, specifically Virginia. Many Upper South slave owners would essentially breed slaves on their plantations and then sell them to Lower South states, which was incredibly lucrative. One Virginia slaveowner wrote in 1820 “a woman who brings a child every two years [is] more valuable than the best man on the farm.” For these reasons, southerners remained committed to allowing slavery in the new territories.

On the floor of the House, Representative Thomas W. Cobb of Georgia looked Tallmadge dead in the eye and told him: “you have kindled a fire which all the waters in the ocean cannot put out, which seas of blood can only extinguish.” While Cobb overly dramatized the situation, southern outrage over the Tallmadge amendment unified southerners against their northern counterparts and these whispers of sectional tensions grew as the antebellum period progressed. The House vote on the Tallmadge amendment was divided along sectional lines with northern representatives voting 80 to 14 in favor and southern representatives voting 64 to 2, against the amendment. The amendment narrowly passed the House. However, in the Senate southerners maintained greater influence and were able to block the passage of the amendment. The Tallmadge amendment failed which led to a deadlock in Congress. When Congress took their annual recess, the statehood bill lapsed.

When the 16th Congress convened in December 1819 Congressmen reignited debates over Missouri statehood. However, President James Monroe, Speaker of the House Henry Clay and key Senate Democratic-Republicans worked behind the scenes on a compromise to solve this crisis. Senate Democratic-Republicans linked the admission of Maine to the Union to Missouri’s admission, essentially holding Maine statehood hostage. Senate Democratic-Republicans would only let Maine’s statehood bill go through if Congress admitted Missouri into the Union without the Tallmadge amendment. However, most northern Congressmen held out until Senator Jesse Thomas of Illinois (who owned “indentured” workers) proposed that slavery be allowed in Missouri but prohibited in the remainder of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30’ parallel, Missouri’s southern boundary. Enough northern Congressmen came around in support of this Thomas amendment to pass the Missouri Compromise in March 1820. Passed as a package, the Missouri Compromise included the Thomas Amendment and stipulated that Maine (a free state) and Missouri (a slave state) would be admitted into the Union at the same time. This set a precedent that states would be admitted in pairs to maintain sectional balance in the Senate and the Electoral College.

The Missouri Compromise prevented the break-up of the Democratic-Republican party along sectional lines. Although the party eventually split following the presidential election of John Quincy Adams with the Clay and Adams’ faction forming the National Republican Party and Andrew Jackson’s faction forming the Democrat Party. Unfortunately, Monroe’s role in this compromise is largely forgotten even though he was instrumental in its passage. The bill launched Clay’s reputation as “the Great Compromiser,” a reputation which continued until his death in 1852. This spirit of compromise prevailed throughout the antebellum period until the 1850s when sectional tensions reached its peak, in part because Clay helped orchestrate a variety of congressional compromises. In 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise by replacing the Thomas amendment with popular sovereignty, which led to Bleeding Kansas. Maintaining sectional balance was tantamount, and the Missouri Compromise essentially settled debates of the expansion of slavery in territories; only to be reopened thirty years later with the Mexican Cession.

Further Reading:

- What Hath God Wrought: the Transformation of America, 1815-1848: By Daniel Walker Howe

- Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson: By David S. Reynolds