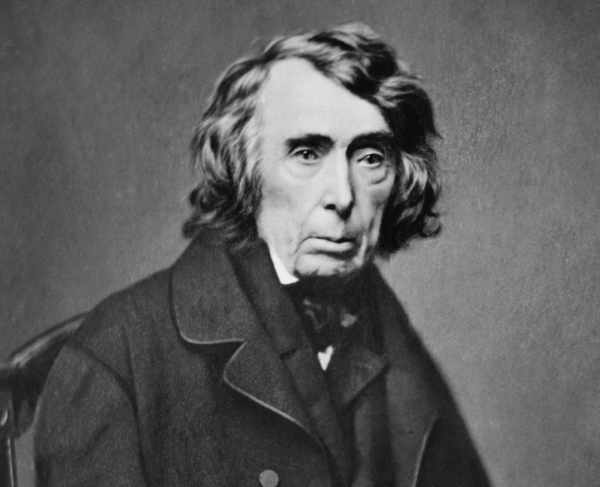

Roger B. Taney

One of the most controversial figures in the decades leading up to the Civil War, Roger Brooke Taney was born on March 17, 1777, into a prominent slave-owning family in Calvert County, Maryland.

Taney studied law at Dickinson College, graduating in 1795 after being elected class valedictorian. Four years later he was admitted to the bar. He was then selected to the Maryland House of Delegates as a Federalist, where he served one term, losing his seat in an anti-Federalist surge. Afterwards, he moved to Frederick, Maryland, where he practiced law for nearly two decades. In 1806, Taney married Anne Phoebe Carlton Key, sister of his friend Francis Scott Key, future author of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” He and Anne would have six daughters together.

When the War of 1812 came to Maryland, Taney distinguished himself as the leader of the “Coodies,” Federalists who supported the war. He was then elected to the House of Delegates again, serving from 1816 to 1821.

Soon after, Taney and his family left Frederick for Baltimore, where he was soon recognized as a talented lawyer. Soon known as one of the leading lawyers in the state, Taney was made Attorney General of Maryland in 1827. By now, Taney was a staunch Democrat in the likeness of Andrew Jackson, who was riding his popularity to the presidency. Taney’s support for Jackson and his notability as Maryland Attorney General led Jackson to appoint him to the prestigious post of United States Attorney General.

Taney played a leading role in Jackson’s administration, becoming a national figure in politics, especially during the Bank War. Jackson vehemently attacked the Second National Bank as undemocratic and unconstitutional. Taney shared his president’s views and was outspoken in criticizing the national bank. He saw it as a tool of Northeastern financial interests that abused its powers, and that its funds should be withdrawn and deposited into state banks. Its charter was set to expire in 1836, but there was movement in Congress to renew it. Jackson and Taney would make sure that did not come to fruition. Jackson nominated Taney for Secretary of the Treasury in 1833, a post in which Taney served faithfully for nine months in crippling the bank. However, so many congressmen opposed his financial policies that Congress refused to confirm him – the first time Congress had refused to confirm a presidential cabinet nominee. Thus, Taney left Washington to return to Baltimore and his law practice.

Despite this humiliation, this was far from the end of Taney’s political career. In 1835, Jackson nominated him to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court. However, like in 1833, Congress refused to confirm him. Less than a year later, however, Chief Justice John Marshall passed away, and Jackson nominated Taney for the position. This time Taney was confirmed for the post, despite strong opposition from prominent congressmen such as Henry Clay, John Calhoun, and Daniel Webster.

A hallmark of the Marshall Court had been expanding federal power at the expense of states. Thus, many onlookers wondered how this Jacksonian states’ rights lawyer would fill the shoes of the eminent Marshall. Although he didn’t completely reverse the Court’s tradition of upholding federal supremacy, Taney subscribed to the doctrine of “divided sovereignty,” that the state and federal government shared power, and it was the Court’s job to decide which powers belonged to which entity. However, in deciding cases about divided sovereignty, Taney would transfer some power back to the state level. He also introduced new practices into the Supreme Court that are still adhered to today, such as wearing ordinary pants underneath robes and the Chief Justice assigning opinions to individual justices.

One of his earliest cases was Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837), where Taney differed from his predecessor in taking a more flexible view of the Contract Cause in the Constitution, which prohibited states from impairing company contracts. He argued that any vague language in a contract should be interpreted to favor the public, not the company.

However, Taney would gain the most notoriety from his decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857). Although he was from the South, Taney personally didn’t believe in the institution of slavery, having emancipated his slaves in 1818. But along with a belief in the inferior status of Black Americans, he believed emancipation should be gradual and left to the states. He thought that Northern abolitionists were tearing the Union apart. On March 6, 1857, he ruled that Dred Scott, an enslaved man who spent significant time in free territory, was not free. He also took the decision further by declaring that African Americans, whether enslaved or free, were not citizens guaranteed to the protections of the Constitution, and that Congress could not constitutionally prohibit slavery in the territories, invalidating the Missouri Compromise of 1820. This decision heightened sectional tensions, with Southerners hailing it as a victory and Northerners violently condemning it. It also undermined the prestige of the court, both in the short and long term, as the decision had been largely shaped by partisan politics, and the constitutional sanction on slavery would forever remain a blot on its record.

The outrage in the North over Dred Scott would help propel Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860, followed by secession and civil war. Taney would clash with Lincoln during the war, whom he privately blamed for starting the war. The most famous of these confrontations wo/uld be over Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. In Ex Parte Merryman (1861), Taney ruled that only Congress had the power to suspend the writ. Lincoln ignored the decision entirely, arguing that public safety and urgency required the suspension.

Taney died in Washington in 1864, after nearly thirty years on the bench, in the midst of a war he had played a large role in helping to create.