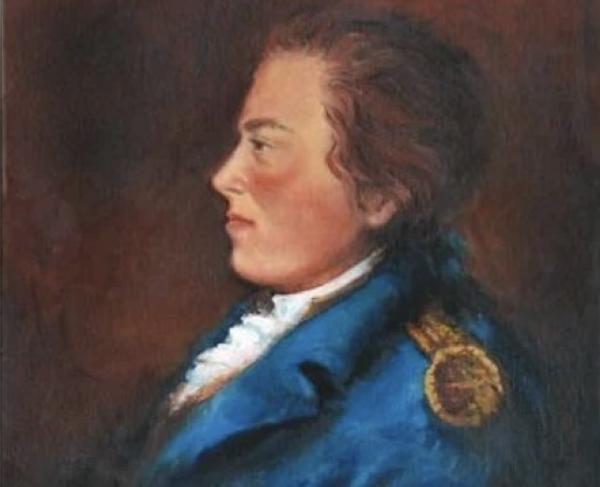

William Franklin

On January 13, 1775, the British appointed governor of New Jersey, William Franklin, stood in front of the New Jersey Legislator and implored them to remain loyal to King George III. “You have now pointed out to you, gentlemen, two roads,” he said, “one evidently leading to peace, happiness, and a restoration of the public tranquility--the other inevitably conducting you to anarchy, misery, and all the horrors of a civil war.” Two years earlier, the Sons of Liberty had thrown 342 chests of tea into the Boston Harbor. Protests had erupted through the thirteen colonies, and the First Continental Congress has met the previous fall to enact an economic boycott on British Goods. Franklin asked for reconciliation with Britain. The Legislature voted unanimously to support the budding revolution.

Ironically, William Franklin was a staunch loyalist, while his father, Benjamin Franklin, was one of the founding fathers of the upcoming revolution. Franklin was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on February 22, 1730, as an illegitimate son to Benjamin. His mother’s identity was never known. He was raised by Benjamin’s common-law wife Deborah Reed and openly acknowledged by his father. As a child, Franklin helped his father write the Poor Richard’s Almanak, assisted with his many science experiments and learned the printing trade. At sixteen, he joined the provincial troops in King George’s War (1744-1748) and ended his enlistment with the rank of Captain in 1747. In 1759, he sailed to London to study law at Middle Temple. While there, he produced an illegitimate son, William Temple Franklin, and married Elizabeth Downes.

Through extensive networking by Benjamin Franklin, Franklin was able to secure the royal position of Governor of New Jersey and became the longest-serving royal governor of the state. His tenure directly correlated to his impressive job as governor: he helped reform roads, construct bridges, and secure crop subsidies from England. In addition, he encouraged the New Jersey legislature to grant a charter for Rutgers University, which has since become the state university of New Jersey. Even though revolution started brewing in the 1770s, Franklin remained as Royal Governor because of his good name and the good name of his father.

By 1776, Benjamin Franklin encouraged Franklin to join the revolution. As a veteran of King George’s War, Benjamin argued that he could receive a high-ranked position in the Continental Army and, because of his good work as Governor, he could have a significant political role in the new nation. However, Franklin refused. He was a devoted member of the Church of England and he believed in Great Britain’s ability to stop the American insurrection. In January 1776, he was placed under house arrest and ousted from his role of royal governor by the Continental Congress. Six months later, he was transported and imprisoned in Wallingford and Middletown, Connecticut.

While imprisoned, he continued garnering support for the loyalist cause by sharing information about the Continental Army and creating a network of loyalist Americans. When news of his activity emerged, he was placed in solitary confinement in Litchfield, Connecticut, for eight months. He unsuccessfully asked for a furlough to see his dying wife, which was denied, and she died while he was incarcerated.

In 1778, Franklin was released in a prisoner exchange and traveled to British-occupied New York City. Once there, he became the leader of the American Loyalists near and around the city. He began to secure aid for the British Army and American Loyalists and create an unofficial spy network of civilian Loyalists. A supporter of guerilla warfare, he organized the Associated Loyalists that used guerilla tactics to fight Patriots in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. While British commanders were initially hesitant of this type of war, these operations became sanctioned in 1780. However, these efforts did not stop the British defeat at Yorktown in October 1781. The next year, Franklin headed to London with the belief that Great Britain could still win the war. He continued to garner support for the cause until Britain’s eventual surrender with the Treaty of Paris, brokered by Franklin’s father.

William Franklin and Benjamin Franklin never reconciled their differences. Benjamin refused compensation or amnesty to Loyalists leaving the colonies during the peace talks in Paris, which directly hurt his own son. In his will, Benjamin left Franklin with several worthless tracts of land in Nova Scotia with the reasoning that if Britain had won the war, he would have had no wealth to leave his son. Franklin attempted to reconcile with his father in 1784 via a letter but received only a chilly reply. They met for the last time in 1785 for a short meeting that regarded financial matters. William Franklin remained in London for the rest of his life and died there in 1813. He was buried in St. Pancras Old Church, but the grave has since been lost.