Mount Holly

Iron Works Hill

Burlington County, NJ | Dec 21 - 23, 1776

History records the plight of the Continental Army in December 1776 as one of desperation: disease, starvation and plummeting morale coming on the backs of repeated defeats around New York City in the fall of 1776. General George Washington’s army, at one point some 20,000 strong, had now dwindled to about 3,000 by early December. It would be remembered as America’s darkest hour. Thomas Paine, writer of Common Sense, would write his second pamphlet, “The American Crisis,” stating that these are the times that try men’s souls…

The Americans were on the far side of the Delaware River in the woods around Newton, Pennsylvania. Washington was reeling from the disastrous events of the past months, and as he accessed the situation, the impossible seemed like his only option: attack the enemy. The Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776, would prove to be the moment that brought America back from the brink. The Declaration of Independence, i.e., The United States of America, was not yet seven months old. Washington’s victory would help ensure its survival. But as we are about to see, an often overlooked series of engagements centered on a town in Burlington County, New Jersey, may have played an indirect but decisive role in ensuring Washington’s victory at Trenton.

The British had established a string of garrisons across central New Jersey, extending from New Brunswick along the Raritan River, with access to the Raritan Bay to the east, to the west among small towns such as Kingston, Princeton, Maidenhead and Trenton, the last being the state capital that overlooked the Delaware River. The best way to view these garrisons is to imagine a spear, with the tip of the spear being Trenton. The spear was pointing at the British army’s next target: the rebel capital of Philadelphia.

On December 13, 1776, British General William Howe placed Hessian Colonel Carl von Donop in command of the forward garrison of Trenton. Leaving the actual command of Trenton in the hands of Colonel Johann Rall, Donop instead was directed to encamp in Bordentown, five miles south of Trenton along the river and readily able to reinforce the garrison if necessary. Howe and General Charles Cornwallis, who lingered for a few days at New Brunswick, soon departed, leaving Major General James Grant of the British 55th Regiment of Foot in command of New Jersey. Donop had under his command the 42nd Regiment of Foot, known as the Royal Highlanders from Scotland under Lieut. Colonel Thomas Sterling; three battalions of Hessian grenadiers under the commands of Lieut. Colonels Linsing, Block and Minnigerode; the 2nd company of jagers under Captain Johann Ewald, a detachment of Hessian artillery with six three-pounders, and one company of British artillery with two six-pounders and two three-pounders. All told a force between 2,400-3,000 troops that was separate from Colonel Rall’s 1,400 mixed Hessian and British troops at Trenton.

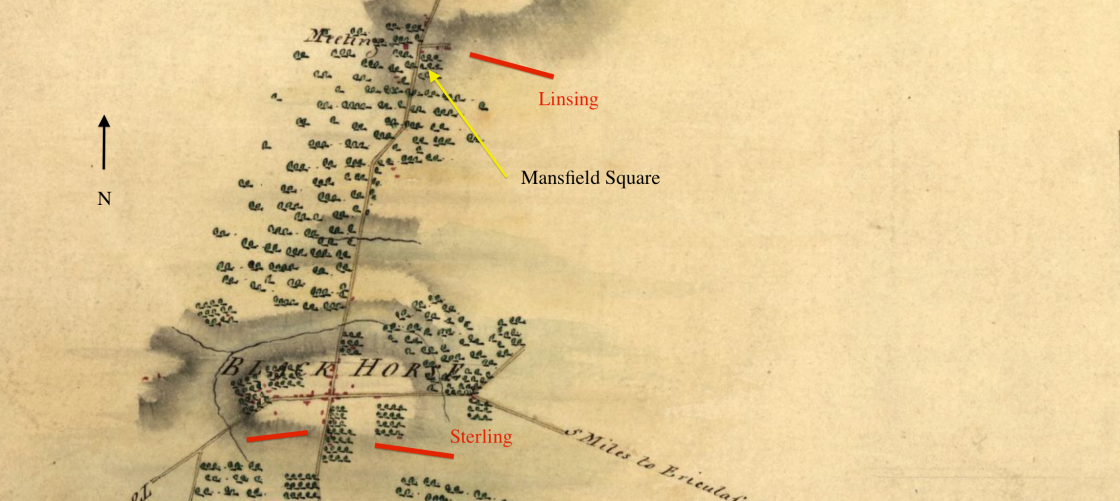

Encamping as one proved to be impossible with a force this size so Donop moved detachments across the countryside east and south of his position at Bordentown. Some troops were placed to the east at Crosswicks while the Linsing Battalion was moved to Mansfield Square, three miles to the north of Black Horse [Columbus] on December 15. The 42nd Highlanders and the Block Battalion were stationed at Black Horse. That same day, the colonel received a dispatch stating American Major General Israel Putnam had a force of 3,000 troops moving in the country below him. A detachment of 200 grenadiers found no such army in the vicinity.

Colonel Samuel Griffin of Virginia was a deputy adjutant general of the Flying Camp in Philadelphia. Griffin was ordered by General Putnam, also stationed in Philadelphia, to assemble a force in the counties of West Jersey to harass the Hessian garrisons south of Trenton. Given two companies of Virginia regulars, the remainder of volunteers from Philadelphia appear to have been boys no older than sixteen. Further militia from Cumberland, Gloucester and Salem counties rallied to give Griffin a combined force of about 600 with a handful of small field pieces, possibly three. After crossing into New Jersey, Griffin established his headquarters at Haddonfield before moving onward to Moorestown. Apparently his health began to fail on this march. It was now the third week of December.

Thursday, December 19th

On this day, Hessian Colonel von Donop decided to inspect the country beneath his position at Bordentown.

Captain Johann Ewald writes,

“On the 19th Colonel Donop ordered me to accompany him to Black Horse to inspect the cordon of the left wing. The colonel took along Captain [Frederich Heinrich] Lorey with twelve mounted jagers, an officer and thirty Scots, and Colonel [Thomas] Stirling to reconnoiter the area of Mount Holly. We arrived at the village unhindered, where we obtained information that Colonel Griffin with two thousand men was stationed at Eayrestown [Lumberton], seven miles from Mount Holly. At eight o’clock in the evening we arrived back in Bordentown.”

From this entry, we can see that the Hessians were comfortable extending themselves from Bordentown to Mount Holly, a distance of about 12 miles. We also see that someone in town stated Griffin lingered in the area with 2,000 troops. Whether this information was deliberate misinformation or was passed along sincerely we do not know. Griffin did not have a force that size; however, the information came four days after the dispatch reporting General Putnam’s army. This phantom army would remain on Donop’s mind in the following days. When he returned to Bordentown, a dispatch from Colonel Rall at Trenton stated he worried that his right flank facing Pennington to the north was exposed to enemy pickets. Assuming Rall was in full command of the situation, Donop’s attention focused on the Delaware River and the town of Burlington to his south.

Friday, December 20th

Ewald continues,

“At three o’clock on the morning of the 20th, Colonel Donop ordered me to proceed at once to Burlington with a detachment of thirty jagers and fifty grenadiers to learn the true situation of the enemy row galleys. He said he had requested heavy artillery from the Commanding General which he expected any day under escort of the fourth Hessian grenadier battalion. As soon as it arrived he would march to Burlington to drive off the row galleys there and occupy the town, whereupon he promises to give me the post at Mount Holly with all the advantages accruing therefrom.”

From here, we gather that Donop’s primary concern remained the naval galleys lingering on the Delaware River. Viewing them as a threat to Burlington and Bordentown, Donop requested artillery support from General Grant at New Brunswick.We also see that Donop promised Ewald command of Mount Holly once Burlington was secured. This places Ewald’s seniority and importance in high view among Donop, and that the colonel saw value in retaining the town’s position, one in the center of the county and situated among the Rancocas Creek, then capable of accommodating small galleys and flat boats. But it’s what Ewald says next that stands out.

“I thanked him for his kindness, but I could not resist saying that I feared the cordon was extended too far, and that I firmly believed despite all the talk of the wretched condition of Washington’s army, that Washington would still undertake something, especially when he was in a position to lose everything otherwise.”

As confirmed by other reports circulating among the British and Hessian ranks, there was rampant speculation that Washington would try some sort of offensive. And judging Ewald’s keen military sense, he recognized the Americans were in such dire straits that an attack was likely the only thing left for them to do. Indeed, financier Robert Morris wrote to Washington on December 21, “I have been told to day that you are preparing to Cross into the Jerseys I hope it may be true & promise myself Joyfull tidings from Your expedition….” It seemed everyone knew something was in the air, yet only Washington could choose the time and place of the attack.

Ewald returned from Burlington the following day, finding Donop “not pleased that the galleys had been reinforced by two schooners.” Donop also received a letter from Colonel Joseph Reed, adjutant general to Washington, discussing saving Burlington from being decimated by cannon fire from the American galleys. As Donop too wanted to avoid any losses to his troop, he welcomed the note and responded, but Reed’s focus soon turned to Mount Holly.

Saturday, December 21

The following day, December 21, Ewald took his post at Bustleton, a small intersection between Bordentown and Burlington, about 4 miles west of Black Horse. Meanwhile Donop remained at Bordentown overseeing the brigade stretched east to Crosswicks and southward to Black Horse. He received a dispatch from Colonel Block midmorning informing him of reports of rebel troops at Mount Holly. Recalling the intel on Putnam and Griffin, Donop promptly sent a rider to inform Rall at Trenton that this could be part of a coordinated attack. But neither Rall nor Donop showed genuine concern of the report. Rall was receiving reports from spies, locals and British intelligence offering conflicting accounts of the strength of Washington’s army.

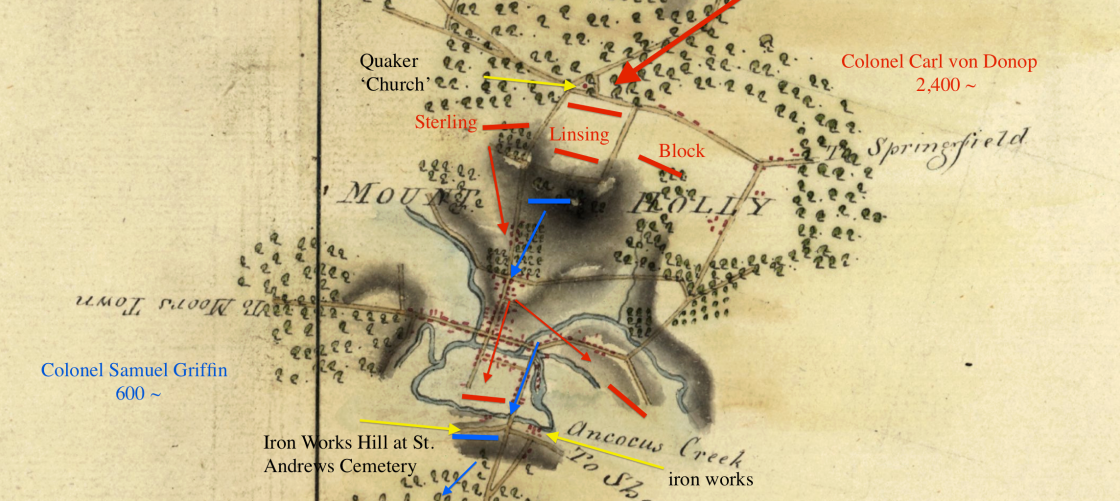

At Mount Holly, Colonel Griffin’s forces constructed an earthworks on the hill above the iron works south of the Rancocas Creek facing north into town. A small chapel belonging to the St. Andrews Church and cemetery resided on the backside of this slope. A second earthworks may have been constructed on the mount that stood on the northern side of the town, facing north towards Slab Town [Jacksonville] and Black Horse. Below the mount stood the old Friends Meeting House that sat adjacent to the Slab Town Road. What occurred in the following hours is unknown but for a small reference in a report given to Donop the following morning.

Sunday, December 22

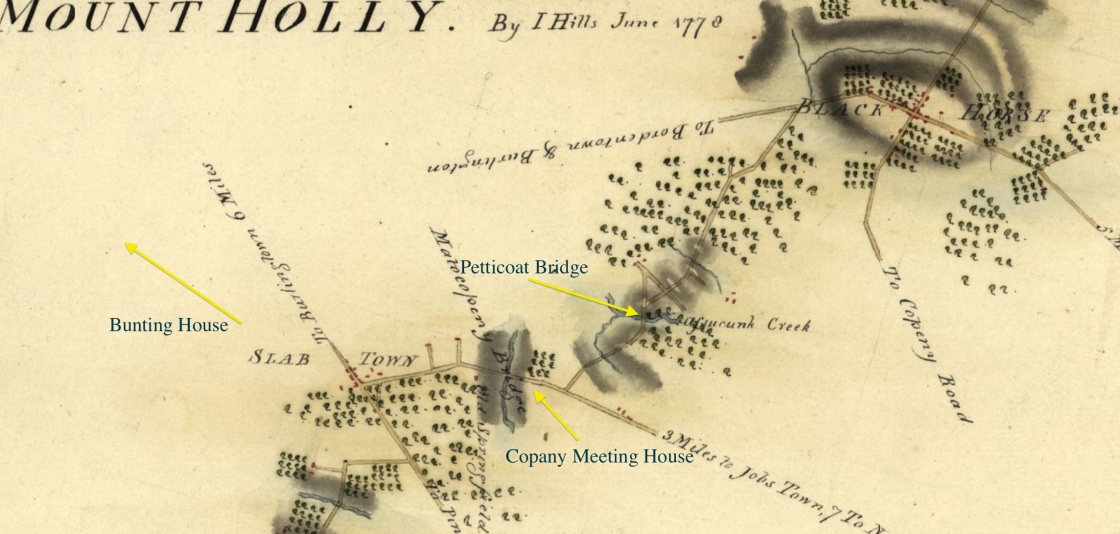

At 4:00am on December 22, Colonel von Donop set off from Bordentown to inspect the cordon at Black Horse. He learned that the Americans had left overnight, suggesting an engagement on December 21 at either Petticoat Bridge, which gave passage over the Assiscunk Creek south of town, or at Black Horse itself. An American picket remained to the north of Mount Holly at the Friends Meeting house along the Slab Town Road. Satisfied with what he saw, Donop returned to Bordentown. About 2:00pm, Donop heard the sound of his cannon from Black Horse. He then heard the signal cannon at the Mansfield Square from Linsing’s battalion. A dispatch was sent to Rall at Trenton, and Donop quickly returned to Black Horse finding the entire battalion under arms. Two German troops were severely wounded while a sergeant and twelve soldiers from the 42nd Highlander Regiment had been chased out of the guard house at Petticoat Bridge by an estimated force of perhaps five hundred American militia. Captain Ernst von Eschwege’s grenadier company intervened, driving the Americans back. Meanwhile, Captain Ewald stood guard at the Bunting House, about 2 miles west of Slab Town.

“In the afternoon of the 22nd I was reinforced with an officer and fifty grenadiers and took post at the Bunting house. This post was situated further on from Black Horse and Bustleton and consisted of a plantation lying upon a hill where the roads coming from Mount Holly and Burlington intersected. Toward the enemy I had woodland, through which these roads ran, and behind me was an extensive meadow.”

Once taking this post, he was fired upon by skirmishers approaching from his southwest around 4:00pm. It appears the Americans did not last long in their offensive and were chased off. Ewald estimated they “withdrew toward Burlington with a loss of several dead and wounded.” He briefly pursued but returned to the Bunting House, citing one jager killed and another severely wounded. He then says he heard muskets and the Hessian field pieces firing in his rear towards Slab Town or Black Horse. He left the Bunting House to report this encounter back at Black Horse. The precise route he took is debated by historians, though it seems likely he traveled through Bustleton as there may have been American militia lingering at Slab Town. Reporting his encounter at the Bunting House, Ewald learned the musket and cannon fire he’d heard in his rear was a fierce battle at Petticoat Bridge between hundreds of soldiers. He had missed this hot fight.

News of the fight traveled throughout the county. In Burlington, Margaret Hill Morris wrote in her diary,

“Several of the families who left the town on the day of the cannonading are returned to their houses. The intelligence brought in this evening is seriously affecting [disturbing]. A party of our men, about 200, marched out of Mount Holly and, meeting with a party of Hessians near a place called Petticoat Bridge, an engagement ensued—the Hessians retreating rather advancing—a heavy firing of musketry and some cannon heard. We are informed that twenty-one of our men were killed in the engagement, and that they returned at night to their headquarters at Mount Holly, the Hessians to theirs at the Black Horse.”

Details here are scattered among the known correspondence; it would appear two scenarios are likely. The first is that the American attack on Petticoat Bridge was to take the position, which they briefly did, and to push the Block and Linsing battalions into an open battle. But given that Griffin’s army were mostly boys and militia, it’s quite possible this fell apart as the Hessian forces went to arms and began firing the three-pounder towards the bridge. The second scenario is that the assault on both the Bunting House and the Petticoat Bridge was a two pronged attack coordinated by the Americans. The reason for this thinking by historians is the correspondence between Colonel Reed and Gen. Washington suggesting Griffin’s men were itching for a fight. More so, Washington was encouraging Griffin to press the issue. With Colonel John Cadwalader being equipped to cross the Delaware to join up with Griffin the following day, it would appear the senior officers were counting on the militia to pull through at Mount Holly.

For instance, Reed writes to Washington the same day, December 22, from Bristol, Pennsylvania,

“Col. Griffin has advanced up the Jerseys with 600 Men as far as Mount Holly within 7 Miles of Their Head Quarters at the Black Horse—he has wrote over here for 2 peices of Artilly & 2 or 300 Volunteers as he expected an Attack very soon. The Spirits of the Militia here are very high—they are all for supporting him—Col. Cadwallader & the Gentlemen here all agree that they should be indulged—we can either give him a strong Reinforcement—or make a separate Attack—the latter bids fairest for producing the greatest & best Effects—it is therefore determined to make all possible Preparation to day & no Event happening to change our Measures the main Body here will cross the River tomorrow Morning & attack their Post between this & the Black Horse, proceeding from thence either to the Black Horse or the Square where about 200 Men are posted as Things shall turn out with Griffin. If they should not attack Griffin as he expects it is probable both our Parties may advance to the Black Horse if Success attends the intermediate Attempt. If they should collect their Force & march against Griffin our Attack will have the best Effects in preventing their sending Troops on that Errand, or breaking up their Quarters & coming in upon their Rear which we must endeavour to do in order to save Griffin.”

Reed sees the situation south of Black Horse as an opportunity, boosted by the “high spirits” of the militia, and determines that Griffin’s request of light artillery and reinforcements would be granted by sending Cadwalader across the Delaware the following morning (December 23). It has been accepted by most historians familiar with the events around Mount Holly that Griffin’s intentions were to create a diversion to draw Donop southward away from Bordentown and far enough away from Trenton that he could not reinforce Rall if trouble came. However, others suggest Griffin’s situation was far more perilous, if he could pull it off. He had been given a tremendous opportunity to engage Donop and draw him into a major battle. This theory bares weight with Reed’s letter to Washington, and is further supported by a meeting held that evening somewhere in New Jersey between Griffin, Reed and Lieut. Colonel John Cox of the Philadelphia Associators. Finding Griffin in poor health, Reed returned to Bristol, Pennsylvania. Overnight, he received another dispatch from Washington, this time with the following,

“The bearer is sent down to know whether your plan was attempted last Night—and if not, to inform you that Christmas day at Night, one hour before day is the time fixed upon for our Attempt on Trenton. For heaven’s sake keep this to yourself, as the discovery of it may prove fatal to us, our numbers, sorry I am to say, being less than I had any conception of—but necessity, dire necessity will—nay must justify any Attempt. Prepare, & in concert with Griffin attack as many of their Posts as you possibly can with a prospect of success. the more we can attack, at the same Instant, the more confusion we shall spread and greater good will result from it.”

Washington wasn’t asking for a diversionary maneuver. He was counting on a coordinated attack led by the combined Philadelphia and Griffin’s forces while he sought to take Trenton. But what organizing went into Griffin’s plans remains unknown.

Monday, December 23

It appears the constant sniping by American pickets and the attack at Petticoat Bridge had frazzled Block’s men at Black Horse. Donop had spent the night in town. With the encouragement of Sterling, who suggested they were a good match for whatever rebel army lay in wait, Donop now agreed the Americans at Mount Holly were his number one threat. Mistakenly thinking the American forces were somewhere between 2-3,000, the Hessian commander decided the moment was ripe for action. And mistakingly thinking that only a few hundred troops were at Black Horse, when the Americans returned to Petticoat Bridge that morning, they instead saw 2,400 German troops marching toward them.

Ewald states,

“On the morning of the 23rd at five o’clock Colonel Donop set out toward Mount Holly with the 42nd Regiment of Scots, the two grenadier battalions, Linsing and Block, the twelve mounted jagers under Captain Lorey, and my jager company. I formed the advanced guard, supported by Captain Lorey and a company of Scots.”

An American volley of muskets checked the front Hessian line. But they soon rallied and returned fire, driving back the Americans, estimated to be somewhere between 50-100. It would appear that what forces were assembling to join the fight now saw the retreating men from the bridge running towards them through Slab Town. American Private Stephen Ford was wounded while standing as a sentry here. Despite the presence of unknown Virginia regulars, the outnumbered Americans never attempted to assemble or counterattack. For their part, as the Hessians advanced they used the Copany Meeting House as a makeshift hospital to threat their wounded. This is where the diversionary tactic theory assumed by historians might have in actuality been irregular disorder by inexperienced militia. This likely explains why Donop and Ewald both breezily describe in their correspondence the running fight that transpired from Slab Town.

Ewald writes,

“In the wood behind Slabtown we ran into an enemy party which took new position at a Quaker church lying on a hill at the end of the wood behind which the entire enemy corps was deployed. The colonel immediately ordered the Linsing Battalion to attack the hill on which the church stood. The Block Battalion was ordered to the left, and the jagers with four companies of Scots under Colonel Stirling, moved to the right through the wood to cut off the enemy from Mount Holly or to gain mastery of the bridge across the Rancocas Creek, which intersects the town.”

Following the Slab Town Road southward back towards Mount Holly, the Americans rallied on the mount itself. On their approach, Ewald noted the Hessians saw a church resting on a hill in the distance. This was the Friends Meeting house, defunct in the 1780s, whose cemetery remains visible today off Woodlane Road. As the ground sloped upward on their approach, Ewald misidentified this hill with the mount, which lay directly behind it. The Hessians came upon the mount, a slope of about one hundred thirty feet, just north of the town. As indicated in Ewald’s journal, Donop divided his forces into three separate units to envelope the hill. The Hessian colonel likely assumed what superior American force he’d been told lay in town waited for him atop the hill in front of him, thus explaining his tactical decision to divide his forces in such a way. The Americans, no more than a few hundred, did not stay on the hill long. Outnumbered, a series of scatter shots were fired through the trees before they made their way to their rear and fell back down High Street into the center of Mount Holly. It was here the Hessians, most likely from the right flank as Ewald states, who gave chase through the streets of town.

Ewald continues,

“The enemy, discovering this movement, withdrew in the greatest disorder through Mount Holly and across the bridge after the grenadiers had taken possession of the church. Since the jagers and Scots pressed closed behind them, a part sought to throw themselves into the house near the bridge, but they were soon dislodged by the fieldpieces. However, the greater part of the enemy gained the wood lying beyond the town, through which the highway ran to Philadelphia, and by which the enemy saved himself. The jagers and Scots pursued the enemy for several miles through the wood, but he made no further stand. Almost two hundred men were captured, two cannon seized, and somewhat over one hundred men may well have been killed on both sides.”

The Americans crossed the Rancocas Creek on the bridge of modern day Pine Street and assumed their fortified position on the hill above the iron works. With the creek in front of them, all the Hessians could do was batter the position with their field pieces. One cannon was positioned to the east on a small slope called Top E Toy (now street) while one was said to be on the mount firing over the town. None dislodged the Americans. As night fell, the firing ceased. Sometime in the evening, the Americans slipped away using a series of trails through the trees and found their way to Moorestown. If what Ewald writes is true about the Hessians capturing two hundred prisoners, Griffin’s force now had been cut down significantly. He had missed his opportunity and now had lost Mount Holly to Donop. However, Donop reported only three American casualties. This second skirmish is what is known as the Battle of Iron Works Hill.

Margaret Hill Morris writes,

“ The troops at Mount Holly went out again today and engaged the Hessians near the same place where they met yesterday. It is reported we lost ten men and that our troops are totally routed and the Hessians in possession of Mount Holly.”

Ewald concludes the day with the following passage:

“The entire corps under Colonel Donop took up the quarters in the town, and I received mine at the exit to Philadelphia. Because of its position, this town is a very excellent trading place and inhabited by many wealthy people. Since the majority have fled and the dwellings had been abandoned, almost the whole town was plundered; and because large stocks of wine were found there, the entire garrison was drunk by evening. Luckily for me, my quarters were in the section most poorly stocked, by which chance the jagers remained fairly sober. Meanwhile, the grenadiers were bringing in so much wine that the majority of the jagers became merry toward midnight, and I had great trouble to keep them together.”

At some point during the day’s battle, Donop had been wounded. As his army settled into Mount Holly for the evening, he found care and comfort in the quarters of a beautiful young widow whose identity remains a mystery. In the meantime, his troops found the liquor supplies left in town and proceeded to celebrate. Combining these two pieces of information with the fact that Mount Holly was the first town Donop’s entire force could encamp together, and that the town had been promised to Ewald as a future garrison site; with Christmas Eve now upon them, it seems no one was quick to leave and return to Bordentown.

Tuesday, December 24

Before news reached Washington that Donop had taken Mount Holly, the general wrote a letter on December 24 to Griffin indicating his plans for the colonel and for Burlington County.

“in the present exigency of our Affairs, to encourage, by every means in my power, the raising of Men for Continental service; and as your Camp may be a proper place to set a Work of this sort on foot, I wish you would select such persons as you shall judge fit to command Companies in the first place and likely to raise them in the next, and promise them in my name, that if they can raise Companies upon the Continental terms, and establishment, or even if they can engage Fifty privates, I will immediately, upon a certificate thereof from you, take both Officers and Men into pay….”

The American commander was placing more responsibility in the hands of Griffin. This shows both Washington’s confidence in the reports he’d been receiving from Reed and his yearning for the patriot militia to disrupt the enemy in New Jersey. Washington also wrote to Col. Cadwalader on December 24, stating,

“Fix with Colo. Griffin on your Points of Attack—In this, as circumstances must govern, I shall not interfere; but let the hour of attack be the 26th, and one hour before day (of that Morning.)”

It is here Washington reveals the plan to attack Trenton would be on the morning of December 26, and that Cadwalader was to combine with Griffin to attack Mount Holly and engage any enemy forces below Bordentown. All of this coordinating was under the assumption that Griffin remained in and around Mount Holly, and that Cadwalader would be in New Jersey with the reinforcements. However, Reed had met up with Griffin on December 24 and found him,

“in bad Health & was inform’d that his Force was too weak to be depended on either in Numbers or Discipline, that all he expected was to make a Division & draw the Notice of the Enemy before whom he proposed to retire if they should advance in any Force.”

This bit is revealing in that Griffin admits his force lacked discipline, a noted problem among militia during the war, particularly when the bulk of them were boys. If you reread the next line, he writes ‘division,’ which likely is ‘diversion,’ a typo by the stenographer who copied this letter for archival purposes. So now Griffin was admitting that he could no longer honor the pledge of going on the offensive. It was here, after losing Mount Holly, that he pivoted to recommend his role be one of diversion. Later that evening, Reed further wrote of Griffin and the militia in Burlington County,

“….urge Genl Puttnam if possible to reinforce Col. Griffin & engage the Attention of the Enemy in that Quarter during the Attack now fixed for the 25th but he found Col. Griffin had returned very ill, that the two Companies of Virginians had also returned leaving their two small Pieces of Iron Cannon & a few Militia at Morris Town [Moorestown] & Haddonfield. Genl Puttnam tho’ anxious to do something found that the Shortness of the Time & the unprovided State of the Militia would not admit of the Corporation [cooperation] design’d….”

What fixed plans of uniting Putnam and Cadwalader’s troops with Griffin’s militia in Burlington County now seemed a moot point. Griffin was incapacitated, his forces were unreliable or dissolving, and it no longer seemed worth the effort to reinforce his position in Burlington County.

Meanwhile, while all of this played out on the American side, the Hessians had remained encamped at Mount Holly since the previous evening. Margaret Hill Morris writes in her journal,

“We hear the Hessians are still at [Mount] Holly, and our troops in possession of Church Hill a little beyond. The account of twenty-one killed the first day of the engagement [Petticoat Bridge] and ten the next [Mount Holly] is not to be depended on, as the Hessians say our men run so fast they had not the opportunity of killing any of them.”

That morning, Captain Ewald went on a patrol in the surrounding area.

“Early on the morning of the 24th I was sent out with twenty jagers and fifty Scots to reconnoiter the road to Moorestown as far as the Long Bridge [Hainesport], to learn if it was occupied by the enemy or destroyed. The road there consisted of a succession of defiles through a thick wood. Toward ten o’clock I arrived unhindered at the bridge and found that it was ruined. Presently a few shots came from the other side where the Americans were hidden in several houses, through which a Scotsman was killed. I deployed the jagers along the [Rancocas] creek to answer the enemy with brisk rifle fire and to reconnoiter the area more closely, after which I withdrew and rendered my report.”

Ewald then inspected Burlington of any galleys still lingering on the river, returning to Mount Holly by midnight. He stated, “The snow had risen so high since yesterday that we could hardly get through.”

While he was on patrol, a trumpeter had come to Mount Holly from Washington’s army inquiring if Donop would be interested in exchanging prisoners held in town. This was determined to be a ruse in order to see if the colonel was staying put or moving back to Bordentown.

Wednesday, December 25

Early the following morning, Christmas Day, Ewald got word that American Colonel Thomas Reynolds was lodging in a house in New Mills [Pemberton]. With Donop’s blessing, Ewald, along with eight jagers and twenty Scots arrived at the house before daylight. Walking in and initially greeted by the room full of people, Ewald then announced everyone was under arrest. Receiving both “good and bad wishes from the beautiful mouthes of the ladies,” he returned to Mount Holly with his prisoners by midday.

At the same time, Col. Reed had informed Washington of the news regarding Griffin’s forces, who responded by writing to General Putnam in Philadelphia on Christmas Day,

“I am sorry Colo. Griffin has left the Jerseys—some active Officer of Influence ought in my opinion, to repair there, to Inspirit the People, & keep the Militia from disbanding & if posible to encourage them to assemble….

P.S. If a party of militia from Philadelphia could be sent over to support the Jersey Militia about Mount Holly, would it not serve to prevent them from Submission; I wish you could get Colo. Forman, and endeavour in my name to prevail upon him to exert himself in this business. I want to see him myself much on this Acct.”

Regardless of Griffin’s state, Washington would not have it, not this close to the final hour. The battle plan was to still include pressing Donop at Mount Holly, even if Griffin was no longer capable of commanding the militia. That left Cadwalader and Putnam with the responsibility of getting across the Delaware into Burlington County. Washington issued his final letter to Cadwalader at 6:00pm on December 25 before mobilizing the army for Trenton.

“Notwithstanding the discouraging Accounts I have received from Col: Reed of what might be expected from the Operations below, I am determined, as the night is favourable, to cross the River, & make the attack upon Trenton in the Morning. If you can do nothing real, at least create as great a diversion as possible.”

Thursday, December 26

In the early hours of December 26, 1776, as Washington’s army embarked on their crossing, Cadwalader wrote to the general,

“We concluded to with draw the Troops that had passed but could not effect it till near 4 O’Clock this Morng—The whole then were ordered to march for Bristol—I imagine the badness of the night must have prevented you from passing as you intended—our men turned out chearfully—We had about 1800 rank & file, including Artillery —It will be impossible for the Enemy to pass the River, till the Ice will bear—Would it not be proper to attempt to cross below & join General Putnam, who was to go over from Philada to day with 500 men, which number added to the 400 Jersey Militia which Col: Griffin left there would make a formidable Body—This would cause a Diversion that would favour any Attempt you may design in future….”

Reed was in Philadelphia with Putnam and similarly indicated the movements of some 500 assembled troops under the general. However, Cadwalader was wholly unaware that Washington made it across the river and had taken Trenton by 9:00am. A second letter from Cadwalader, written at this precise moment, has him asking Washington if their combined forces might envelope Bordentown once he made it safely across. He further writes,

“General Putnam was to cross at Philada to day, if the weather permitted, with 1000 men; 300 went over yesterday & 500 Jersey Militia are now there, as Col: Griffin informs me to day—These Corps compose a formidable Force—The Plan would be more compleat if General Putnam was one days march advanced.”

This indicates there was now a force of 800 militia and volunteers in Burlington County on the morning Washington took Trenton. But without a commanding officer and without a clear plan of attack that would compliment the main thrust of the army up north, whose historic victory had not yet reached these soldiers; the failure of both Cadwalader and Putnam to cross the river between December 23-25 to preserve what mustered troops remained under Griffin’s command eroded the chances of engaging Donop directly at Mount Holly. Cadwalader did make it across on December 27 while Reed and Lieut. Colonel John Cox of the 2nd Regiment of Philadelphia Associators found Trenton abandoned.

Midday on December 26, a bugler rode into Mount Holly informing Donop that Rall was under attack. Before his troop could make way, a second bugler arrived with news that Washington had taken Trenton. It was all over.

200

50

Considering that Colonel Donop was not supposed to be in Mount Holly, and that Colonel Rall had repeatedly ignored warnings by spies and British intelligence, an inquiry was immediately opened into where to place the blame over the loss of the garrison at Trenton. Donop maintained that his intentions at Mount Holly were to rally allegiances and offer pardons. This was the unofficial story for two centuries until Ewald’s diary was uncovered and translated in 1979 to reveal the Hessian captain placing the blame squarely on Donop being under the spell of this ‘widow of Mount Holly.’ More so, Ewald blames the entire loss of the war on Donop’s failure to reinforce Rall at Trenton.

So why did Colonel Carl von Donop swing so far south that he put his priority of protecting Trenton at grave risk? It would seem a combination of the continuous harassment his troops faced at the hands of elusive country militia, his frustrations with not having his artillery to destroy the galleys around Burlington and the faulty intelligence of a sizable American force waiting at Mount Holly prompted him to make a bold strike that unfortunately jeopardized Rall. It appears Donop carried this guilt with him, for the following year he led the disastrous attack on Fort Mercer at the Battle of Red Bank which costed him his life. He is buried on the battlefield.

The other side of the story is what might have happened if Putnam’s or Cadwalader’s detachments made it across the Delaware and joined up with Griffin’s militia? Speculation being our only mode of inquiry, one can see that the additional American troops would have given Donop a real test at Mount Holly. Washington clearly viewed the situation around Mount Holly as vital to pinning down all enemy forces that could assist Rall at Trenton. For their part, had Griffin’s men held off attacking Petticoat Bridge one more day, keeping the Hessians in place and his militia force intact and in ‘high spirits,’ they might have been reinforced by Putnam in time to assemble the sizable force Donop kept hearing about, and who knows then what might have happened? Clearly, Griffin’s illness affected his command of his troops, and what lack of discipline and order they presented in battle is shown through snippets of their behavior under duress. It’s a matter of missed opportunities and the difference of a couple of days. The failures presented here did not matter in the end, for Donop’s ‘mistress’ kept him subdued in Mount Holly and away from Trenton. Thus, the American Revolution once again reveals how ordinary people played decisive roles in helping win the war for independence.

What became of Griffin’s militia in the days after leaving Mount Holly is unknown. His health remained an issue into the new year it seems. He began his letter to Washington on January 30, 1777 by stating,

“I must beg leave to Apologize, for not haveing Answered your Excellencys polite, & Friendly, letter, of 24th of Decr last, in which you Honor’d me with the Offer of a Regiment of Infantry, at the time Colo. Reed dilivered me your favor, I was confined to my Bed, and not able to write, and as I fully Intended to repair to Head Quarters, as soon as my Health would permit….”

Whether Griffin was ill or felt ashamed of the missed opportunity at Mount Holly remains debated, but it is worth our interest that he acknowledges ducking Washington for an entire month after the events in December.

The stroke of attacking and taking Trenton cannot be understated to the effect it had on both the American and British/Hessian armies. While we know it partially rallied the spirits of the Continental Army, Ewald writes on December 30,

“The Americans had constantly run before us. Four weeks ago we expected to end the war with the capture of Philadelphia, and now we had to render Washington the honor of thinking about our defense. Due to this affair at Trenton, such a fright came over the army that if Washington had used this opportunity we would have flown to our ships and let him have all of America. Since we had thus far underestimated our enemy, from this unhappy day onward we saw everything through a magnifying glass.”

Who Was the Widow of Mount Holly?

The biggest mystery of the entire affair is the widow whom Colonel von Donop was with at Mount Holly. Whoever she was, Ewald notes that Donop was taken by this woman.

"Early on the morning of the 26th [December] Captain Lorey and I roamed over different roads in the country to collect horses and slaughter cattle; for the colonel [Donop],who was extremely devoted to the fair sex, had found in his quarters the exceedingly beautiful young widow of a doctor. He wanted to set up his rest quarters in Mount Holly, which, to the misfortune of Colonel Rall, he was permitted to do."

If he was kept in submission by the presence of a widow, surely we owe her our thanks for how events unfolded. Early renditions of this story suggested she was none other than Betsy Ross. However, historians theorizing her involvement misidentified her husband’s profession. John Ross was an upholsterer, not a doctor; therefore, Mrs. Ross cannot be this woman. Dr. John Ross of Mount Holly had a wife but her name was Mary Brainerd, they weren’t married until August 1778 and both lived to the 1790s. Some historians suggest the line “widow of a doctor” was a cover story to protect the young woman from Hessian troops. Consider the appalling stories gossiped about what they did to women, particularly young unmarried ones, it’s not that far-fetched a theory. Others have speculated this widow might have been a spy or double agent, not uncommon during the war. Indeed, Margaret Hill Morris writes on December 22, “All the women [have] removed from the town [Mount Holly] except one widow of our acquaintance.” But what to make of this last line?

Margaret Morris seems to have been very well connected and informed about the knowings of both the Americans and the Hessians coming/going through Burlington, and she even indicates her knowledge of troop movements by both armies. Perhaps this is because of the critical position Burlington found itself in along the Delaware River or its regular arrival of officers and troops from both armies. We also know that Morris had loyalist leanings, yet she seemed to converse with Colonels Reed and Cox without nefarious intentions. Therefore, many have concluded she was a spy. Unfortunately, she, too, never identifies the young widow in Mount Holly.

Other theories suggest she may have been a “widow of war.” Some historians have concluded this woman to be Mary Magdalene Bancroft, wife of Dr. Daniel Bancroft, whom was suspected of loyalist sympathies. Bancroft had been captured by Griffin’s men and sent to Pennsylvania in December 1776. He would later serve as a surgeon for a Loyalist regiment in South Carolina. A key part of this theory, aside from her reported beauty, was her ability to speak French. Donop could not speak English, but he did speak French. However, there is no verifying evidence beyond this.

Why Does It Matter

Without a name or other information to confirm or add to the existing documentation, the identity of this woman remains a mystery. What cannot be dismissed is her importance and her contribution, whether knowingly or unknowingly, to aiding Washington’s victory at Trenton. Despite the inability of Griffin’s men and the failure of both Putnam and Cadwalader to reinforce him, Mount Holly proved to be a catalyst in overcoming America’s darkest hour. With this young woman keeping Donop comfortable and distracted, combined with his brigade’s desire to encamp as one for the first time in weeks, the plentiful supply of alcohol, the inclemate weather, and it being Christmas, the Hessian colonel saw no reason to leave the town, and doubtably ever admitted the truth reasons why Mount Holly had ‘captured’ him in December 1776.

Captain Ewald has the final word,

“This great misfortunate, which surely caused the utter loss of the thirteen splendid provinces of the Crown of England, was due partly to the extension of the cordon, partly to the fault of Colonel Donop, who was led by the nose to Mount Holly by Colonel Griffin and detained there by love….Thus the fate of entire kingdoms often depends upon a few blockheads and irresolute men.”

All battles of the New York and New Jersey Campaign

Related Battles

600

2,400

200

50