Battle of White Plains

The rebellion of the American colonies did more than survive the Revolutionary War’s first year in 1775. American troops fought toe-to-toe with the British Army and defeated them at Lexington and Concord, Fort Ticonderoga, and Montréal while they showed their fighting mettle in a defeat at Bunker Hill. As the year ended, the main British army in North America under Gen. William Howe huddled in Boston besieged by Gen. George Washington’s Continental Army.

Howe, a veteran of the bloodletting at Bunker Hill, knew the British needed to change their strategy in order to win. On March 17, 1776, Howe’s forces abandoned Boston and sailed for Nova Scotia to prepare for their next campaign. Though they sailed north, both Howe and Washington knew where the British would land next when they returned to the colonies: New York City.

Though Washington correctly deduced British intentions, he did not favor his situation in New York. Britain’s naval superiority could rule the many waterways ringing New York City and unhinge any land defenses that Washington selected for his army. Political considerations trumped Washington’s concerns. Americans could not give up their largest and arguably most important city without a fight. Additionally, by the time Howe’s forces (30,000 men strong) launched their offensive against Washington’s army of 19,000 soldiers on Long Island in August 1776, the colonies had just declared their independence a month earlier. Quitting New York without a fight simply would not show the American cause in a good light to its followers or prospective allies.

The Declaration of Independence did not breed battlefield success on Long Island. Instead, British maneuvering—Howe’s trademark strategy—won the day on August 27. Washington abandoned the island two days later. Then, on September 15, the British fleet, under Howe’s brother Richard, shuttled British infantry to Kip’s Bay. This force outflanked Washington’s position in Manhattan and the American general quickly withdrew his army north from the city’s streets to Harlem Heights along the Hudson River. The next day, portions of the two armies engaged again. Washington’s men gained the upper hand and nearly drove Howe’s forces back to their camp. This fight infused the Americans with a much-needed morale boost and stole Howe’s momentum; he settled his army into the city and strengthened his position over the next month.

On October 12, Howe resorted to maneuver yet again to flank Washington out of his Harlem Heights defenses. A defensive stand at Throg’s Neck stopped Howe’s latest attempt but it only prolonged the inevitable—Washington decided to vacate Manhattan Island on October 16. Fort Washington remained in American hands. Two days later, Howe used the East River again to envelop the American position by water. Fighting broke out at Pell’s Point as Washington’s main body raced north to establish a new defensive position atop high ground at White Plains. Once more, a delaying action and swift marching allowed the Americans to win the race and escape the trap Howe set for them.

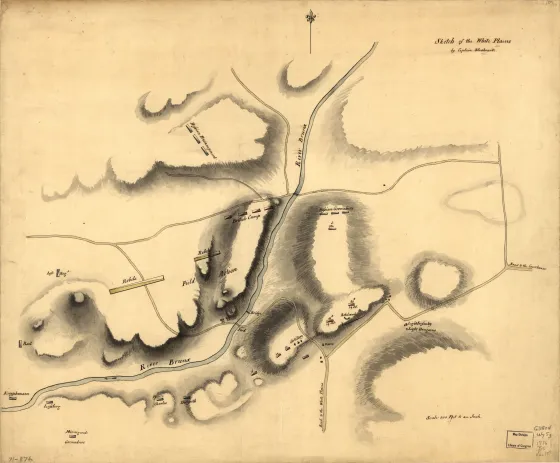

Howe advanced on Washington’s army at White Plains on October 28 with a force of 13,000 British and Hessian troops. The British and Hessian force marched in multiple columns. Howe’s plan slated the rightmost column under Lt. Gen. Henry Clinton to outflank the American left.

By the time Howe moved against Washington, the American commander had his 14,000-man army safely ensconced on high ground overlooking White Plains behind constructed defensive works. Israel Putnam’s division held the American right, William Heath occupied the left, and Washington himself commanded the center. Washington anchored both flanks on bodies of water and bent both flanks backward to protect their rear against another of Howe’s envelopments. Despite its strengths, Washington’s White Plains position was not flaw-free. Across the Bronx River, upon which Washington placed his right, stood a hill 180 feet above the waterway known as Chatterton’s Hill. It stood one-half mile from the American right and could be used by the British to enfilade Washington’s line.

Washington staged an active defense. His men met Howe’s advancing column one and a half miles in front of the main line and doggedly resisted the British from stone wall to stone wall as they slowly fell back closer to the primary American position. Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rall’s Hessian regiment outflanked the advanced Americans several times and drove them across the Bronx River to Chatterton’s Hill. Colonel Rufus Putnam commanded two American militia regiments who were in the process of belatedly fortifying the hill. Seeing the hill’s importance, Washington ordered Col. John Haslet’s 1st Delaware Regiment to reinforce the militia. Colonel Alexander McDougall’s brigade soon followed Haslet.

British artillery opened on the hill’s defenders. One shot struck a Massachusetts militiaman in the thigh and prompted the entire regiment to panic. While the artillery pounded away, British infantry on the plain below deployed for battle. “Its appearance was truly magnificent,” an American officer wrote. “A bright autumnal sun shed its lustre on the polished arms; and the rich array of dress and military equipage gave an imposing grandeur to the scene as they advanced in all the pomp and circumstance of war.” The British high command dispatched 4,000 men and a dozen artillery pieces to capture Chatterton’s Hill.

Following an artillery barrage that Haslet compared to “a continual peal of reiterated thunder,” the British line lurched forward. The rain swollen Bronx River presented an impediment to the assault. Howe’s men attempted to construct a crude bridge across the river to gain access to the hill on its west side until Gen. Alexander Leslie learned of a ford a short distance downstream. The 28th and 35th Regiments of Foot were the first across and immediately charged up the slopes of Chatterton’s Hill. Terrain and a wall of fire from atop the hill stopped the first assault.

The British resorted to maneuvering next to seize the hill but the Americans parried those attempts ably. While the barrage of the hill proved useful, it began to endanger the British and Hessian attackers as much it did the American defenders. The guns fell silent, and the next wave of European attackers moved up the hill. Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rall’s Hessian regiment rushed the American right, which briefly held until the militiamen there saw British dragoons sweeping down on there flank, which forced them to run for safety. Haslet’s 1st Delaware moved to cover the recently vacated right flank; Rall’s men met them head-on. Haslet’s Blue Hens held but the American line gradually cracked under the weight of the assault. The Delaware men held to the last but ultimately were swept from Chatterton’s Hill.

On the British right, Clinton struggled to advance. “I was certain the instant they discovered my column, they would retire,” he wrote. He sought to get around the American left with a column under Charles Cornwallis but before this flanking force made much progress, the Americans withdrew in the face of Clinton’s threat.

Leslie’s successful attack and the occupation of Chatterton’s Hill unhinged Washington’s line. He pulled back to a second range of hills, North Castle Heights, in the American rear, where he laid out his army’s next defensive line. Howe’s success came with a cost, however. British and Hessian casualties totaled 313 men, one of whom may have been the inspiration for Washington Irving’s Headless Horseman in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Tallies of American casualties vary widely from 150 to 500 casualties. Regardless, the range of numbers demonstrate the quick and panicked American flight from the field of White Plains.

Howe notched another victory in his belt at White Plains while Washington’s Americans suffered another defeat. Unfortunately for the British, weather became Howe’s greatest impediment to capitalizing on the victory. Heavy rains and wind prevented Howe from pressing the Americans again, despite several attempts to renew his offensive. Finally, Howe returned his army to New York City.

The Battle of White Plains is repeatedly referred to as a small engagement even though many thousands of troops were within earshot of the action. Indeed, while it is not clear if a Hessian casualty at White Plains inspired Washington Irving’s ghostly antagonist, he nonetheless wrote of the figure that he was “the ghost of a Hessian trooper, whose head had been carried away by a cannon-ball, in some nameless battle during the Revolutionary War…” White Plains was not a nameless battle, but in the larger scheme of the Revolutionary War, it does not equate to more well-known battles. For Washington’s army, it was the latest battle to forget in a string of them. The British held the battlefield at the end of October 28, 1776, but could not exploit the advantage gained by the action. But Washington now turned his attention away from the defeats of New York and into New Jersey, where future—though unlikely—victories awaited him at Trenton and Princeton.

Related Battles

217

233