The aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg was horrible beyond belief. Thousands of grievously wounded soldiers lay strewn across the fields or consolidated into public or private buildings hastily converted into hospitals. In addition to the crucial work done by army or civilian doctors, private organizations offered additional care and resources. The United States Christian Commission was one such private organization that followed the Union army in order to both provide physical goods and assistance as well as to improve their religious lives. Founded in 1861 in New York City, the Christian Commission was heavily involved after the Battle of Gettysburg. Agents of the Commission were traveling with the Army of the Potomac prior to the engagement, and as early as July 4 and 5 additional staff were pouring into the town and converting a local newspaper office into a Commission headquarters.

Arriving in the area, the organization brought wagons full of supplies to various hospitals and established stations at nearly every corps hospital that historian Gregory Coco described as “usually a tent or two filled with supplies and necessities, with one or more agents present to help the wounded and issue the materials.” Beyond the stations at major hospitals, agents spread across the smaller buildings pressed into hospital service, ministering both material goods and spiritual assistance to Union and Confederate alike. A Commission Report recorded that upon arrival, agents “commenced their labors with the wounded, washing from their persons the dirt and blood of battle, removing, whenever it could be done, their torn and blood-matted clothing, and placing them in positions as comfortable as could be provided.” From their main office and smaller tents, the Commission disbursed all manner of goods, ranging from soft bread, brandies, or jellies to clothing or medical supplies. As smaller aid stations slowly consolidated as recovered soldiers left and badly wounded men relocated to Camp Letterman, the Christian Commission followed.

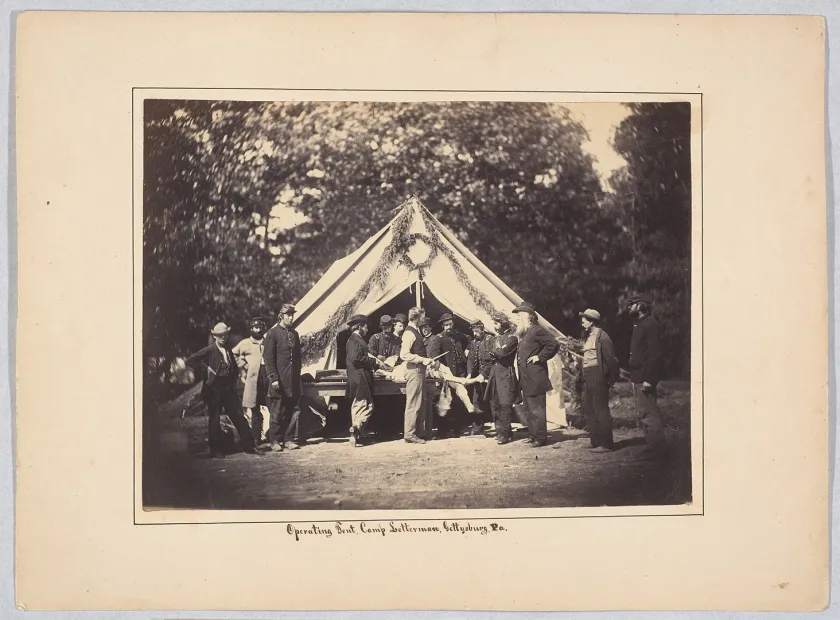

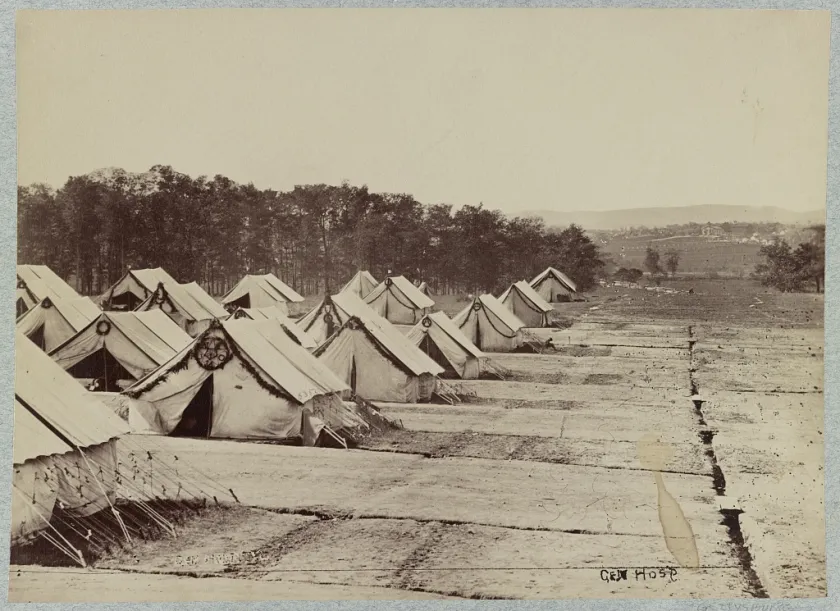

Opened on July 20, Camp Letterman was created when Union doctors consolidated the wounded, both Union and Confederate, from numerous field hospitals and private homes. Though most wounded had been transported away from Gettysburg, nearly 4,000 men too badly wounded to transport remained. Located on these eighty scenic acres near a spring on the York Turnpike, the camp held thousands of soldiers while they were treated between July and November 1863. George Wolf’s house and outbuildings rested roughly one thousand yards southwest of the hospital site and were not used. This land was chosen for many of the same reasons it had been popular for picnics: elevated, well-drained land, consistent movement of air, freshwater, shade, and convenient location near both the road and a railroad. There, doctors examined patients and performed operations while numerous nurses attended to the wounded by delivering food, bathing the wounded, and offering comfort.

Nurse Sophronia Bucklin recalled that at Camp Letterman the organization did their work “nobly,” and remembered a woman from the Christian Commission would take a wagon to the countryside daily and return with “generous gifts of fowls, eggs, milk and butter.” In addition to distributing food and clothes, they would gift bibles or prayer books as well as lead religious discussions. Though sometimes criticized by a similar secular organization, the United States Sanitary Commission, for focusing on religious conversion over physical assistance to the wounded or dying early in the war, they did good work. At Camp Letterman, the Christian Commission operated five tents where in addition to the normal dispersal of goods they operated a library with “shelves well filled with reading matter” that agents and nurses gave to the wounded. The eight Commission delegates were always busily at work meeting with medical personnel, distributing goods, conducting religious services, and visiting the wounded. These physical and spiritual comforts were of great help to suffering wounded at the hospital, whether Union or Confederate. Their assistance is exemplified in the documentation by Reverend R. J. Parvin, a Commission delegate, about his ministrations to Corporal David C. Laird of the 4th Michigan Infantry.

On July 2, 1863, Laird was badly wounded near the spine while fighting in the Wheatfield. By July 31, Laird had been moved to Camp Letterman and throughout his recovery, Reverend Parvin repeatedly met with Laird to offer comfort. Parvin wrote: “I found on the field a Michigan soldier named David Laird, and visited him regularly while I was at Gettysburg. . . .At first he was very much troubled because his wound – a serious one received while the regiment was falling back under orders – was in the back.” Laird was concerned about the nature of his wound. Having been shot in the back, he feared others would deem him a coward as it might appear he had fled from battle. Parvin wrote letters on Laird’s behalf to his family explaining the situation. A letter from Laird’s father helped to assuage those fears, stating “As to David’s wound in the back, it need give him no uneasiness. None who know him will suppose it to be there on account of cowardice.” With this news, Laird could be certain neither his friends nor his family doubted his bravery. Key to Parvin’s account, however, was Laird’s spiritual health. The prelude to the story stated, “The most precious reward to the Delegate was the privilege of turning a wandering soul to Jesus,” and Parvin noted that his interactions with Laird included a story of the wounded soldier speaking “of his early training, of his wandering from it, of his longing to return.” Laird had been raised a Christian but had apparently distanced from that faith. Through long conversations and both physical and spiritual aid, Parvin was convinced that Laird had returned to religion.

Despite assuring others of his bravery and a religious revival, Laird’s situation worsened. Parvin noted: “The weeks passed on; the pleasant September days came, but David was worse. His father came in time to see him die.” The final entry in Laird’s medical record was as follows: “Sept 5th to 24th, Failing up to last date when Death occured[sic].” He was buried in the Camp Letterman cemetery, and eventually moved to the Gettysburg National Cemetery, where he rests evermore in grave B-22 in the Michigan plot. Much of Laird’s story falls within the Victorian nature of the Good Death, a topic examined by many recent historians, notably Drew Gilpin Faust’s 2008 This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. Essentially, a Good Death involved commitment to religion and the presence of loved ones. Though many soldiers were denied this during the Civil War, the religious counseling of Reverend Parvin and the arrival of his father allowed David Laird to fit within this mold and have a more socially acceptable death than most others. Parvin’s account ends with him trying to comfort David Laird’s father and being told “I don’t need any comfort from man, for God has given me so much, in seeing the happy death of my boy, that I am perfectly content.”

Members of the Christian Commission provided physical goods and immeasurable spiritual aid to soldiers throughout the war and were very much present in the aftermath of the battle of Gettysburg. Whether in the fields and hospitals strewn around the battlefield and town or in the more organized site of Camp Letterman, delegates of the organization provided needed support. Working with the military and other civilian volunteers such as the United States Sanitary Commission, the Christian Commission endeavored to ensure that wounded or dying soldiers would have both their physical and intangible needs met during a time in which normal supply lines were inadequate and volunteers were needed more than ever. In the cases of David Laird and countless other soldiers, the Christian Commission eased physical pain with necessities and luxuries while helping to provide comfort not only to the dying but also to the families of soldiers but ensuring their final moments fit in more closely with society’s expectations of the Good Death.

Further Reading:

- A Strange and Blighted Land, Gettysburg: The Aftermath of a Battle By: Gregory A. Coco

- Gettysburg & the Christian Commission By: Daniel J. Hoisington

- Incidents Among Shot and Shell By: Edward P. Smith

- Second Report of the Committee of Maryland, September 1, 1863. By: United States Christian Commission

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...

Related Battles

23,049

28,063