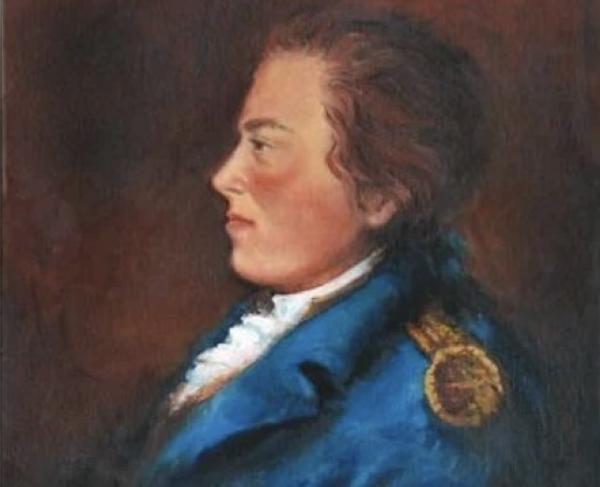

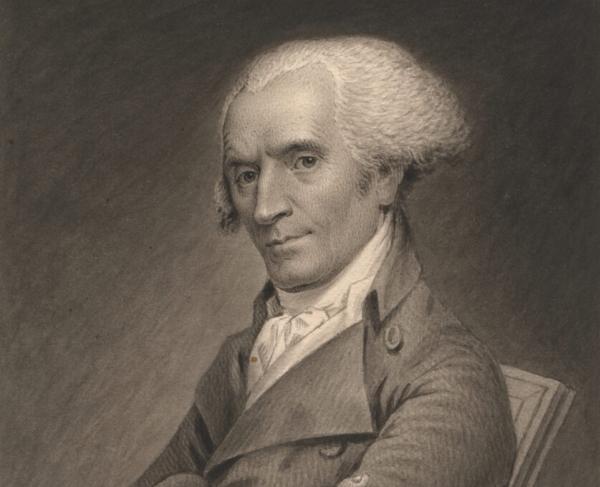

Thomas Hutchinson

Thomas Hutchinson was born on September 9, 1711, in Boston, Massachusetts. His father was a wealthy merchant, and his great-great-grandmother was Anne Hutchinson, a religious dissenter who was banished from the Massachusetts Bay colony in 1637. Young Thomas enrolled in Harvard College at age 12, and earned his degree in 1727 at the age of 16. Ten years later, in 1737, he was elected to the Board of Selectman which governed the town of Boston. The next year, Hutchinson was elected to serve in the General Court, the Massachusetts colonial legislature. He also served as a member of the governor’s council and as the chief justice of the Superior Court, the highest judicial position in the colony. Hutchinson was also interested in history, and in the 1760s he published the first two volumes of a history of Massachusetts.

In 1754, tensions were rising between the British and French colonies in North America. Thomas Hutchinson attended the Albany Congress, where representatives from several of the Thirteen Colonies met to try and achieve greater cooperation. Hutchinson and other delegates debated different plans for colonial union. They ultimately endorsed a proposal created by Benjamin Franklin, called the Albany Plan of Union, but the colonial assemblies rejected the plan as too encroaching on their authority and it was never formally proposed to the British government. In 1758, Thomas Hutchinson was appointed as the new lieutenant governor of Massachusetts. This raised some protests from Massachusetts men like John Adams and James Otis, because Hutchinson was now serving simultaneously as lieutenant governor, a member of the governor’s council, and the chief justice.

Hutchinson would remain a steadfast Loyalist as relations between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies worsened, but he also was an advocate for restraint. He argued against the Stamp Act of 1765, which ignited a storm of opposition and resistance in the colonies. While Hutchinson believed the Stamp Act should be repealed, he wrote that he saw no way that “Government could have conceded to the claims of America, without admitting their principle of total independence.” Hutchinson tried to moderate Massachusetts’s opposition to the Stamp Act, which led his political opponents to claim that he supported the law. The Sons of Liberty organized mobs, which intimidated Hutchinson’s brother-in-law Andrew Oliver into resigning his position as a tax collector and vandalized the homes of other colonial officials.

On August 26, 1765, a mob marched on the Boston home of Thomas Hutchinson, who barely escaped before the rioters arrived. The mob ransacked the house, smashed furniture, destroyed the home’s cupola, and even tore down interior walls in the house. Hutchinson’s papers were scattered and destroyed, including research and notes for the third volume of his history of Massachusetts. Hutchinson submitted a detailed inventory that estimated the total cost of the damage and theft at 2,200 pounds – around $545,000 today.

The Stamp Act was eventually repealed, but the imperial crisis continued. Parliament passed new taxes, called the Townshend Acts, and stationed troops in Boston. In 1770, during an altercation between colonists and the redcoats, five colonists were killed when the soldiers opened fire. Hutchinson was serving as acting governor at the time, and he took steps to calm the city. He had the soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre arrested and held for trial, and he requested the withdrawal of all British troops from the city. The Boston Massacre shook his confidence, and he wrote a letter to the British government resigning from the position. As the resignation letter was traveling across the Atlantic to Britain, a letter arrived from Britain appointing him to the position of governor. His resignation was rejected.

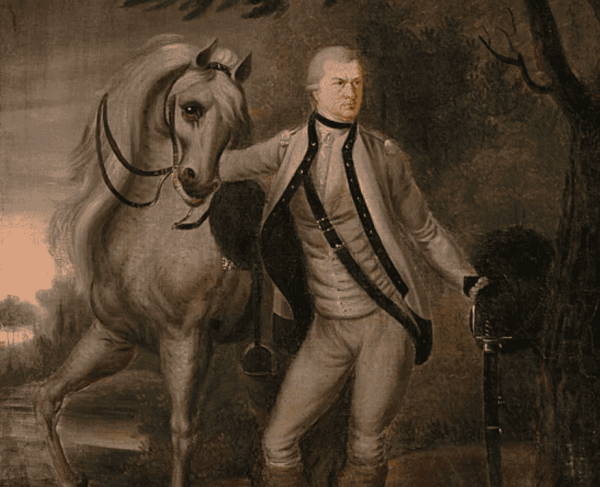

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act. When three ships arrived in Boston harbor with tea from Britain, Governor Hutchinson insisted that the ships would not leave the port until their cargo of tea was unloaded. On December 16, 1773, Bostonians stormed the ships and dumped the tea into the harbor. The Boston Tea Party provoked outrage in London, and Hutchinson was replaced by a military governor, General Thomas Gage. Hutchinson traveled to Britain, advising the royal government on the situation in the colonies, but when the Revolutionary War erupted, he became an exile. His property in Massachusetts was seized by the revolutionary government. Hutchinson spent the rest of his life in Britain. He worked on a third volume of his history of Massachusetts, which covered his own time in the colonial government. It was published posthumously on June 3, 1780.

Governor Hutchinson was a key figure in the events that led to the American Revolution. His efforts to carry out the British government’s colonial policies in Massachusetts inflamed opposition to royal rule. Many famous revolutionaries, like John and Samuel Adams, made their reputations as opponents of Thomas Hutchinson.