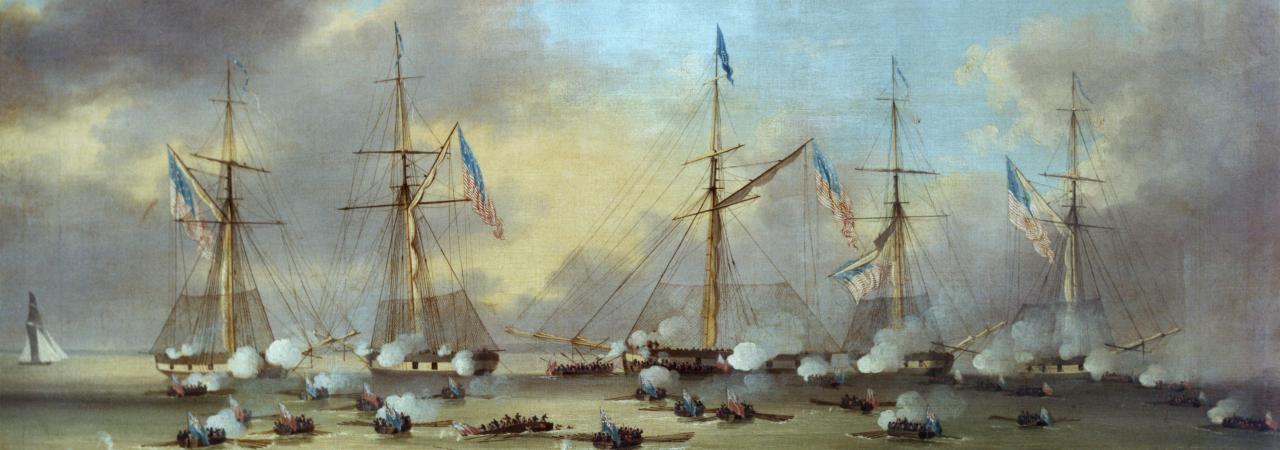

Naval Engagements Around New Orleans during the War of 1812

The Treaty of Ghent was signed in Belgium on December 24, 1814, officially ending the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain. Although American and British diplomats agreed to a peaceful resolution, news of the treaty and its ratification did not reach the American and British militaries until May 1815.

As peace negotiations occurred in 1814, that winter, the British Royal Navy planned an assault on the port city of New Orleans. Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane of the Royal Navy convinced the admiralty that an attack on the mouth of the Mississippi River would weaken the United States. Cochrane's plan involved the Royal Navy blockading and transporting 8,000 troops into New Orleans, Louisiana. The British knew that cutting off the mouth of the Mississippi and seizing the Crescent City some 95 miles north of the Gulf of Mexico would cause the American South and West to lose access to trade and necessary resources for survival. Around September 5, American Secretary of War James Monroe warned Major General Andrew Jackson of the British military's incoming attack on New Orleans. Jackson and his men immediately left Mobile, Alabama, and traveled to Louisiana to prevent the British arrival along the Gulf Coast. While Jackson and his men began to travel to Louisiana, the Royal Navy approached the mouth of the Mississippi. Admiral Alexander Cochrane ordered the HMS Armie and the Sophia to sail near Bayou Bienville and look out for American ships. As the three ships patrolled the area, they established rendezvous points for the future attack on New Orleans. When the vessel entered Lake Borgne, they met a squadron of five American gunboats led by Thomas Catesby Jones. Two of Jones' gunboats fired on the British flotilla and caused both sides to retreat briefly to prepare for battle.

Admiral Alexander Cochrane needed to defeat the flotilla of American gunboats to get 8,000 troops into New Orleans successfully. After evaluating the lake, it was determined that it was too shallow to send a ship off the line to pursue the American flotilla. Instead, Cochrane placed the commander of the Sophie, Nicholas Lockyer, in command of a fleet of British rowboats. Under Lockyer, forty-five open boats and barges were equipped with carronades and contained 1,200 sailors and Royal Marines heading towards Jones. On December 12, Lockyer's men rowed through the night towards Lake Borgne, and it was not until late the following day that Jones' fleet was in range. Once the enemy fleet was in sight, Lockyer divided the men and assigned them different targets to pursue, including the American sloop, the Seahorse. Lockyer sent three barges to the Bay of Saint Louis to capture or sink the Seahorse. Spotting the approaching British barges, the American sailors fired using three six-pounders. After forty minutes of fighting, the British retreated; knowing they were at a disadvantage, the American captain blew up the Seahorse to prevent the British from gaining an additional ship. As some British barges pursued the Seahorse, the rest of the fleet advanced toward the rest of Jones's gunboats.

Due to harsh weather conditions, Lockyer and Jones' fleet was forced to stop and rest for the evening. Once the wind settled the following morning, the British advanced toward Jones. Due to his compromised position within the Rigolets of Louisiana, the crew began preparing for the oncoming fight with the enemy. At 10 am, Jones' squadron of five gunboats met forty-two of Lockyer's heavily armed barges. Once in range, two gunboats unsuccessfully fired down upon the enemy. Lockyer's barges are fast and small, making them a hard target for larger ships, giving the British the advantage. As the battle progressed, two barges were sunk due to failed attempts to seize Jones' ships. During the heat of the fight, a musket ball hit Jones on his shoulder, forcing him to retire below deck. Command of the American fleet fell into the hands of George Parker. By mid-day, Lockyer's men successfully boarded and seized one of the gunboats and fired on the rest of Jone's fleet. Confused, the American fleet continued to fight, aiming at both the lost gunboat and the advancing barges. The British quickly overwhelmed the Americans and surrendered at 12:40 on December 14.

The British lost seventeen men, and seventy-seven were wounded. Despite the British victory, the American fleet suffered ten deaths. As Lockey men raided the ships, the American sailors were questioned about the size of Jackson's incoming army. With a rough estimate of a couple of thousand men heading toward New Orleans, Cochrane's fleet set sail toward the mouth of the Mississippi. With the removal of the American fleet, Admiral Cochrane sailed toward Pea Island with General Edward Pakenham and his men to lay siege to New Orleans. The British military established Pea Island as a mutual meeting point for additional incoming troops. As the British continued to build their forces, Jackson received word about Jones' loss at the Battle of Lake Borgone. Desperately, Jackson requested assistance from Commodore Danieal Patterson and militiamen from Kentucky to prevent the loss of New Orleans to the British.

Jackson and American Commodore Daniel Patterson began collecting supplies to face the British on land and sea. After the Jones' loss, the American navy around New Orleans consisted of three ships, the Louisiana, Carolina, and a remaining gunboat with ample ammunition. Fortunately, Admiral Cochrane decided against sailing up the Mississippi River due to its extreme difficulty. By doing so, Cochrane yielded naval superiority to Patterson's small flotilla. As the British troops grew at Pea Island, Patterson, and Master Commandant John Henley, sailed the Carolina down the Mississippi and fired upon a British unit. Surprised British troops ran for cover from the cannon fire, which was used to signal Jackson's troops to attack. Jackson and his men boldly met the enemy in a nighttime attack. Fighting ensues for several hours until Jackson and his men retreat into the night near Rodriguez Canal alongside the river. The Americans established a marine battery in preparation for retaliation by the British.

As Jackson's men prepared for the incoming assault from General Edward Pakenham's troops, Louisiana and the Carolina continued to patrol the waterways in search of British encampments. On December 27, the Carolina sailed down the river, approaching a heavily armed British unit near Villere Plantation. Once spotted, the unit began firing using heated artillery, also known as hot shots, at the Carolina. Henley and his men were forced to abandon the ship, and moments later, the Carolina exploded, killing one sailor and wounding six more. After hearing about the fate of the Carolina, Louisiana sailed upriver to avoid the artillery fire and protect Jackson's troops. The sinking of the Carolina prompted Pakenham and his men to begin marching toward New Orleans. As the British marched towards the city, Commodore Patterson removed a few cannons from Louisiana and placed them along the west bank of the Mississippi River to protect Jackson and salvage some of the guns if the ship sank in combat. Not wanting the British to gain another ship nor lose Louisiana to gunfire, the hip was retired, leaving Jackson with no naval defense. On the morning of January 8, General Pakenham's 8,000 men faced Andrew Jackson's unit of 5,700 at Chalmette Plantation for the Battle of New Orleans.

The battle for New Orleans was a swift victory for the United States. Jackson and his men utilized earthworks and volleys to damage the British line. The Americans suffered 13 casualties, a minimal loss compared to the British defeat of 291, which included General Edward Pakenham. The victory on January 8 aided Jackson's popularity and his presidential campaign in 1828. The British did not leave Louisiana after the defeat at Chalmette Plantation; instead, the navy remained for a week and made it a goal to destroy Fort St. Phillips. Fortunately for the United States, Jackson had strengthened the fort years prior by adding additional mortars and howitzers to the battery. After the battle, the remaining American gunboat and four hundred regulars occupied the fort, anticipating a British attack. Cochrane and his fleet began firing on Fort St. Phillip to damage and distract Jackson, safely retreating the British soldiers back to the ship to flee. Cochrane's bombardment caused enough damage to be taken as a viable threat and captivated Jackson's full attention. On January 18, the British officially left the mouth of the Mississippi and returned to Great Britain.

On February 14, 1815, news of the official ending of the war reached New Orleans. Although the battle occurred after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, it played a significant role in the United States' victory during the War of 1812. The United States grew in popularity and dominated the high seas after back-to-back victories against the British Royal Navy.

Related Battles

62

2,034