Continental Congress: Unprepared for War

In July 1776, the Continental Congress voted and passed the Declaration of Independence. In that document, 13 of Great Britain’s North American colonies declared their formal separation from the mother country. To achieve that aim, the main Continental army—then in the field around New York City, New York—would need to gain a victory against their counterpart, the British military, through a decisive battle or campaign or prolonging the war until the British citizenry grew weary of the high cost of the conflict. The Continental Congress had a role to support the army and war effort as the governing body of the colonies during the American Revolutionary War.

Declaring independence was a matter of great importance. Maintaining the army, developing the apparatuses of government, and creating a system of governance that could claim legitimacy would be another consideration and challenge. The Continental Congress, initially filled with the leading figures of the respective colonies, continued to either come up short or outright fail in the duties a government needed to perform in order to be efficient.

In regards to ideology, the Continental Congress was ready for war by the time the Declaration of Independence was finally agreed upon. In all other matters, however, the same political body was woefully unprepared. The most glaring weakness of the Continental Congress was the lack of assertion when it came to raising revenue and taxes.

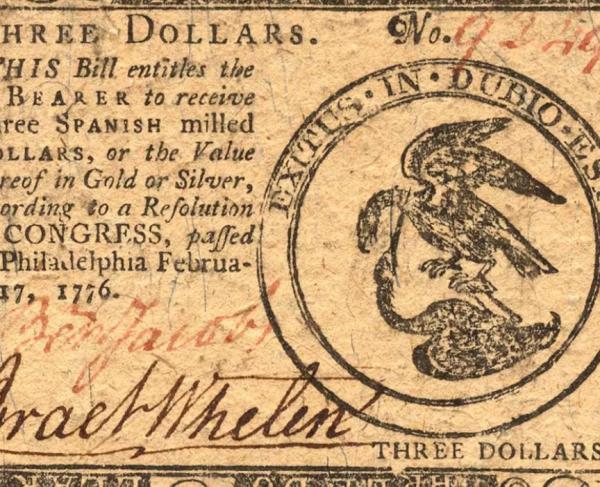

To support an army, money is needed to pay the men and to buy supplies, munitions, and cover various other expenses in order to successfully win the war. Without enforcing taxes within the colonies, the Continental Congress had no money-generating capability. The Continental Congress asked the states to support the war by sending funds; the Congress could insist, but it had no mechanism to force the states to comply and provide the requisite amounts. As one historian explained, the Continental Congress was in the business of spending money yet had no way to continually raise the money the body spent.

In addition to raising the revenue to purchase supplies and pay for soldiers to stay in the field, a support structure had to support that army and military effort, and one did not exist on the scale needed. The Continental Congress had no established supply system, no national distribution, and no purchasing system. Compounding these problems, no one in the colonies had ever led a system of the magnitude needed for the war effort. Congress had to learn as the war progressed, but lacked the establishment to act decisively on any of these matters. Instead, the Continental Congress existed on a series of temporary measures that continued to plague General George Washington’s army and the various other Continental army units that were raised throughout the war.

As the war progressed, the Continental Congress saw the brightest minds continue to vacate their positions in the Congress and head back to their respective colonies, leaving a void of effective leadership. At times during the crucial moments of the war—for instance during the winter at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania in 1777-1778—only 18 delegates attended sessions. Previously, in 1776 when the Declaration of Independence was adopted, 49 delegates had been in attendance in Philadelphia. Approximately 55 percent of the delegates that served in the Continental Congress during the war stayed in their position for more than a year. A mere 25 served more than 35 months of the 100 months between July 1776 and November 1783. This large turnover within the ranks of the political body governing the war effort contributed to the Continental Congress’s unpreparedness. When delegates resigned, retired, or were replaced, the trickledown effect created uncertainty within the entire system of government. Contracts went unfulfilled, payment stopped, and essential decisions, such as ratifying treaties or managing the army, fell by the wayside.

The euphoria of declaring independence and abolishing the restraints the British Parliament put on the 13 separate colonies quickly waned when faced with the complex realization of how these same states were to be governed. Reacting to the abject fear of a centralized power wielding ultimate authority, the delegates to the Continental Congress created a system dependent on the states to maintain many of the prerogatives of national government. When the Continental Congress deferred the taxation question to the states, it forfeited its primary role in enabling the army to win the war. Wars are expensive and continue to rack up costs as the conflict progresses. The Continental Congress spent the entire war begging and cajoling the various states to provide funding and supplies to keep the Continental army in the field. Even that, at various times in the war, in December 1776, at Valley Forge, and Newburgh, New York in 1783, happened only by the slimmest of margins.

With the lack of centralized power, the Continental Congress was hamstrung throughout the conflict. Rapid turnover in the ranks of delegates and having to improvise a system of government to a scale beyond anything any individual in the colonies had attempted before, meant that the task of managing the war effort was herculean. As one historian aptly titled a history of the American Revolution, the victory of the colonies over the British was “almost a miracle.”

Independence quickly ensured that the United States and its representatives would need to devise a slightly better form of government.