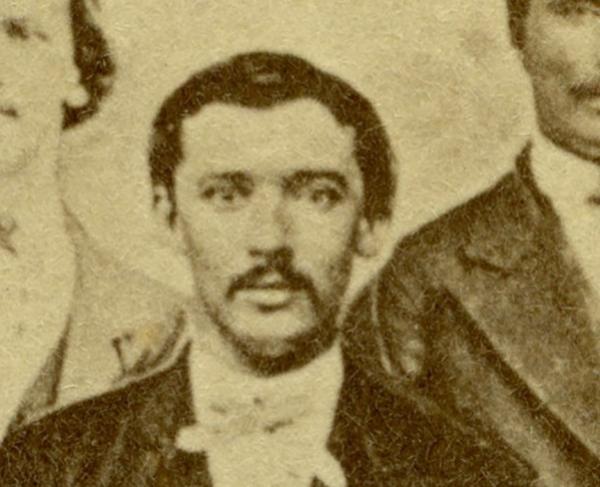

Andre Cailloux

Andre Cailloux experienced slavery, freedom, military service, and officer leadership in his Louisiana life during the Antebellum and Civil War eras. His choices were complex and efforts to maintain freedom for himself and his family.

Cailloux was born into slavery on August 25, 1825, in Plaquemines Parish near New Orleans, Louisiana. His parents were enslaved and lived on neighboring plantations. The family practiced Catholicism, and Cailloux and his siblings were baptized. In June 1830—weeks before Cailloux’s fifth birthday—his mother was sold, and he and his father were taken into the city of New Orleans. As he grew older, Cailloux learned the trade of cigar making. He may have been allowed to earn money for himself or there may have been an arrangement with his enslavers that extra work or money went toward his eventual emancipation.

In 1845—following local laws—Cailloux’s enslavers petitioned the Police Jury of the Orleans Parish and the Third District Court of New Orleans to manumit Andre Cailloux. On July 8, 1846, he was freed from slavery. New Orleans increased regulatory laws involving the free Black community, but approximately 11,000 free African Americans lived, worked, and built community in the city on the eve of the American Civil War.

Cailloux married Louise Felicie Coulon, signing a legal marriage contract on April 18, 1847, and observing a religious marriage ceremony on June 22, 1847. Felicie’s mother had been granted freedom, and she had purchased her daughter in 1841 and legally manumitted her around 1846. When Andre and Felicie Cailloux married, he legally adopted her son, Jean Louis, raising the boy as their own. Together, the Caillouxs had four children: Eugene, Athalie Clemence, Odile, and Hortense (died in infancy). They baptized their children at the parish church of St. Theresa of Ailia and sent them to Catholic schools.

Professionally, Cailloux was one of 156 cigar makers in New Orleans, which numbered the third largest group of artisans in the city. By 1848, he had saved enough earnings to purchase a small lot of land for $200 cash. The following year Cailloux purchased his mother out of slavery. During the 1850s, he moved his growing family into an uptown, free African American neighborhood and successfully paid off the mortgage on his home in 1856. He took an active role in social organizations and was elected an officer in the Society of the Friends of Order and Mutual Assistance which aided the Black community. Despite these successes, Cailloux—contrary to later stories—was not wealthy, and he sometimes struggled to pay taxes and to compete in business with large cigar making factories.

On January 26, 1861, Louisiana voted to follow the path of other southern states and declare secession. White men rallied their militia units or formed new regiments, eager to join the Confederate cause. Free men of color in New Orleans considered their options, meeting publicly in April. They looked to historical precedents from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 when freemen had fought and hoped to advance or retain their limited social status. They wondered what would happen if they did not show support at least a nominal support alongside white citizens of Confederate New Orleans. Ultimately, about 1000 free men agreed to support the state and offer their military services to the Louisiana governor who authorized the formation of the Louisiana Native Guards. Andre Cailloux was elected a First Lieutenant, serving in the Friends of the Order Company. The Native Guards were required to purchase their own weapons and uniforms and were commanded by a white colonel. The Confederacy viewed the unit as a show regiment and did not prioritize military training or equipment.

By April 1862, Union forces closed in on New Orleans. The Native Guards received orders to disband and were not trusted to help defend the city. These free Black men quietly returned to their homes and did not attempt to relocate or form their unit elsewhere with other Confederate troops. Union occupying troops, commanded by General Benjamin Butler, offered freedom to enslaved people under the “contraband of war” precedent.

In July 1862, former Black officers from the Louisiana Native Guards approached General Butler, explaining their local unit and offering to reform as Union volunteers to fight for freedom. Weeks later, on August 22, 1862, General Orders 63 allowed the formation of the Union 1st Louisiana Native Guard Infantry. Andre Cailloux again stepped forward and recruited a company, becoming their captain. He was one of 19 Black officers commissioned in this Union regiment and received $60 per month, equal pay with white officers of the same rank; taking a traditional American-English form of his name, he signed his Union regimental papers as Andrew Cailloux.

The regiment was sent to guard and fatigue duties in the autumn of 1862. Pay was delayed, much to the frustration of the men who still tried to support families in New Orleans. In January 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, formally bringing freedom for enslaved people into the Union’s war aims. Andre Cailloux, in his blue uniform, went to Fort Jackson and in the early spring moved with the regiment to the vicinity of Baton Rogue, then on to Port Hudson.

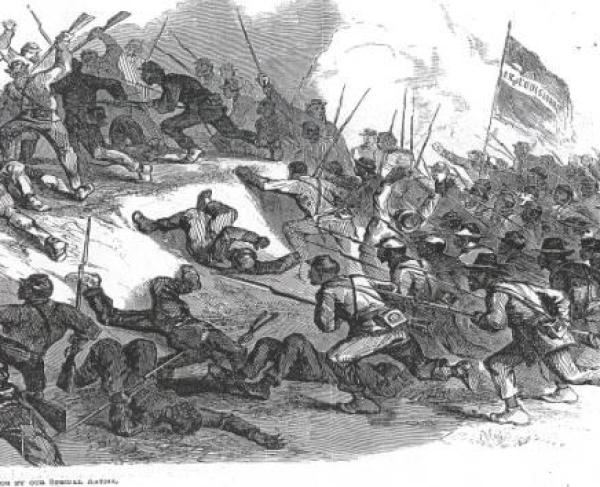

Union General Nathaniel Banks hoped to capture Port Hudson quickly. One of the last key Confederate strongholds on the Mississippi River, Port Hudson was defended by Confederate earthworks on high ground. A large-scale Union assault was planned for May 27, 1863, and the 1st Louisiana Native Guards prepared to take part in the attack. Captain Cailloux took his place in the regiment’s battle line, prepared to lead his company against the Confederate position in their front. The regiment charged forward and reformed three to six times, trying to move across rough terrain under Confederate fire. Cailloux urged his men on, shouting orders in both English and French to communicate with the Black soldiers under his command. His left arm was broken, but he gestured forward with his sword in his right hand until pieces of an artillery shell struck him in the head, killing him instantly.

Despite the brave charges, the Confederate earthworks held, and Union troops finally fell back on May 27. A flag of truce allowed the removal of white wounded and dead from the battlefield, but the Native Guards where not allowed to rescue their casualties from the battlefield. However, Confederate soldiers took items from the Black soldiers’ bodies; they took Cailloux’s officer’s commission and eight dollars from his corpse and did not bury his remains.

Port Hudson surrendered to Union forces on July 8, 1863. At that time—40 days after the May attack—Captain Cailloux’s remains were identified, laid in a coffin, and taken to New Orleans. On July 29, 1863, a public funeral, mourning, and burial brought thousands of Black citizens of New Orleans into the streets to remember and honor Captain Cailloux. Defying orders from a Confederate sympathizing archbishop, Catholic priest Father Maistre preached the religious service and observed funerary late rites. Cailloux’s widow and children attended the service, and dozens of community leaders and organizations followed his casket in the funeral process. Captain Cailloux was interred in Bienville Street Cemetery, and for 30 days, the United States flag in occupied New Orleans flew at half-mast in his honor.

The account and stories of Andre Cailloux at Port Hudson and his funeral briefly swept through Union and abolitionist newspapers. Several abolitionist writers honored him with poetry. However, in Civil War memory the Louisiana Native Guards and its Black officers are often overshadowed by the 54th Massachusetts and that regiments attack at Battery Wagner in July 1863. Andre Cailloux’s memory remained strong in the Black community. Black veterans named Grand Army of the Republic Posts after him, and during the Civil Rights movements, his name was evoked as an example of patriotism and community leadership.

Andre Cailloux navigated sorrows and difficulties, making choices to try to protect his family and Black community. Given the option in 1862, he chose to volunteer to fight in Union ranks and battle for freedom. He died, leading his men in a charge and hoping that his choices and his sacrifice would continue the cause of liberty.

Related Battles

5,000

7,208