Distinguished Photography Corps

Supporters of the American Battlefield Trust contribute to the cause of battlefield preservation in many ways — from online contributions to stock transfers to workplace matching programs — but one very special group gives in the form of their talent rather than their treasure.

Few readers of Hallowed Ground realize that virtually all submissions to the magazine by historians and artists are made as donations. And while many authors are recognized subject matter experts whose books already grace our home libraries, the Trust feels that the talented photographers who make it their work to capture the beauty of these battlefields deserve broad recognition as well.

The American Battlefield Trust “Photography Corps” is made up of those professional and semi-professional photographers who donate the most exceptional work — in terms of quantity and quality — to the Trust for inclusion in the magazine, website and other media. They may have diverse backgrounds and philosophies, but they are united in their passion for capturing the beauty and majesty of battlefields for public enjoyment. They also share a willingness to tackle difficult and unusual assignments, driving long distances or trying to match the contours of topographic maps to an empty field — and, in one memorable instance, camping overnight in a swamp.

Perhaps the first of the Trust’s volunteer photographers, Bruce Guthrie was initially a member of the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites. Nearly two decades later, he is still taking high-caliber shots of battlefields and Trust events. In that time, he’s found that the key to shooting battlefields is to explore them carefully: “Most of them aren’t beautiful in any typical sense, but you know every inch of that ground meant the world to someone — and for many, it was the last thing they ever saw…. Ofttimes the most significant thing you’ll personally get from a battlefield isn’t the battlefield itself. It will be … the penny left on the grave, the shadow cast on the field.”

Many more of these artists, including Lynn Light Heller — who met her husband on a weekend trip to Gettysburg — are also long-term Trust members. After moving to the battlefield community in 2008, she became involved in a number of local history-centric organizations, including the Gettysburg Foundation and Gettysburg Civil War Round Table, of which she is the current president. But for all that time logged on the field, any Trust assignment to re-create images taken in the immediate aftermath of the battle brought her a whole new perspective on the field. “It must have been a comical scene — the ditsy blond, with camera bag, charts, ladder, pushing through the brambles and awkwardly surmounting the rail fence.… But with all that, I was surrounded by beautiful autumn leaves, and a stillness that I have not experienced in other areas of the battlefield.”

Mike Talplacido discovered the Trust via a circuitous, and even literal, route. A former high school history teacher who now works in the telecommunications industry, he has a long history of leading family road trips to historic destinations. One such journey brought family members to Shiloh National Military Park — arriving during the Trust’s 2005 Park Day clean-up effort. “We arrived early, expecting to capture the sunrise over the Tennessee River, but instead we talked to the park rangers about Park Day and decided to pitch in. “We spent the morning meeting nice people from Mississippi, Tennessee and even Michigan, all the while cleaning up the national cemetery and Pittsburg Landing. I have been involved ever since!”

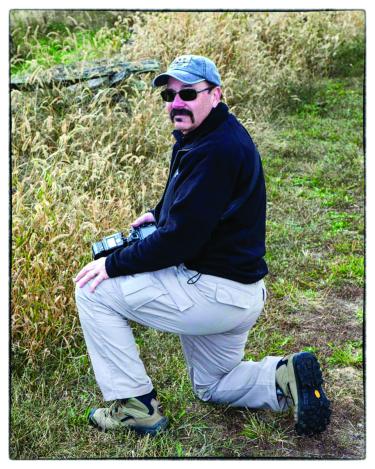

Buddy Secor — an engineer working for the federal government — was inspired to begin photographing historic sites after discovering that his home in Stafford County, Va., was built on the site of a Federal redoubt designed to protect Aquia Creek Landing and the Union army’s 1862–1863 winter encampment following the Battle of Fredericksburg. He shared some of his work with the National Park Service, which quickly enlisted him as a formal volunteer photographer. True to his adopted sobriquet NinjaPix, he often rises at “zero dark thirty” to capture optimal images. “Knowing that thousands of people died for what they believed in on those grounds makes it all [the] more important for me to capture the images as well as I can. I try to chase the light and weather — like fog — to convey a solemn emotion that represents the land in front of me.”

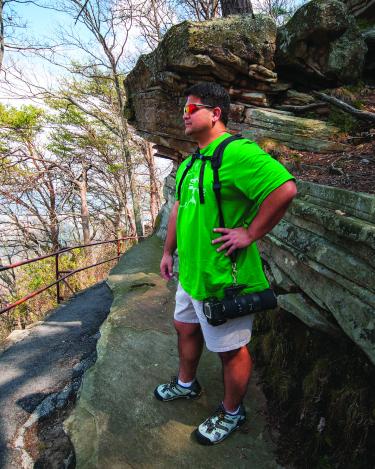

The Trust firmly believes that preserved battlefields are monuments to the bravery of the men and women in uniform who fought there, and understands that members of today’s armed forces feel an especially profound connection to these special places. Shenandoah Sanchez — a Marine combat veteran who became enamored with Civil War history studying under Craig Symonds while a cadet at the U.S. Naval Academy — strives to visualize this relationship in his work. “I find it a truly soulful experience … when I’m out there and it’s really quiet; I will swear that I can hear the sounds, smell the powder, envision the grand formations occupying the fields, feel and understand the intensity of what took place there.”

Similarly, Theresa Rasmussen has spent three decades as a cartographer for the Defense Mapping Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers Army Geospatial Center, so she understands the importance of landscapes in a military capacity intimately. But as a passionate amateur photographer, she began exploring the Chancellorsville Battlefield near her home with a different eye — one that stretched her artistic talents as well. “Shooting battlefields is different, because there is not only so much history, but I can actually imagine what happened on these lands, all those years ago. My favorite photos that I’ve shot on the Chancellorsville Battlefield evoke such strong visuals of what it must have been like to fight there.”

The vast majority of the Trust’s Photography Corps is self-taught, having discovered a love of history and/or photography independently. Pennsylvanian Ron Zanoni received his first camera — a Kodak Instamatic — at the age of 12. “I became the historian for all of the adventures that my friends and I experienced while growing up in New Jersey. In high school, I joined the Photography Club, taking sports photos with an old-style press camera. Other than that experience, I never had any formal photography training, but I read articles on the proper use of the camera and how to photograph different subject matter.

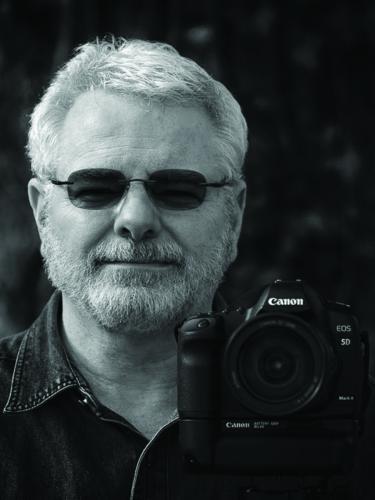

Alternately, there are several professional photographers who do pro bono work for the Trust. James Salzano is a New York City–based photographer who has spent 35 years shooting advertising and commercial and editorial subjects, and has also taught photography through a host of prestigious institutions. He prizes the opportunity to leave the studio and work in such singular, special places. “For me, it is meaningful being in a spot where so many lost their lives. It’s an emotional space that has always left me humble and respectful. I try to respect the history and the land where it all happened, and connect with that emotion.”

For David Davis of North Carolina, photography was far from his first artistic pursuit. “My artistic background has been mostly music, playing guitar in local bands. Then in 2010, my lovely wife Delores gave me a [Canon Digital] Rebel for Christmas, and I have been obsessed ever since.” Thanks to workshops and online classes, his learning curve was rapid, enabling him to turn talent into a new career. In just six years, he has earned awards from the Professional Photographers of North Carolina and the International Photography Awards, and was a finalist for the SIENA International Photo Awards.

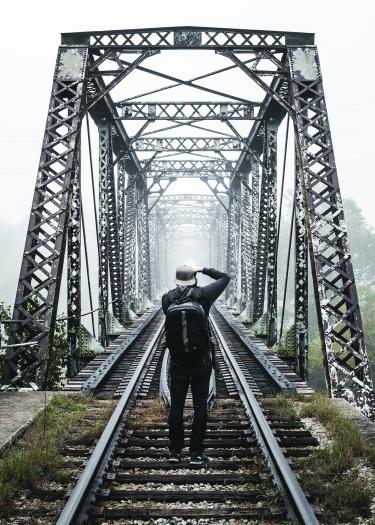

Nicholas Iverson, who is now based on the West Coast, arrived in the hours before dawn to shoot at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park in preparation for the 150th anniversary of the Confederate surrender — an assignment he says produced some of his favorite work. “When you shoot battlefields, you have very little control…. The principles of photography don’t change, though. Lighting is important. Composition is important. Subject is important. Tone and mood are important. But you can’t just move a light or adjust the subject matter. It takes time, patience and high standards.”

A commercial photographer in Richmond, Va., Jamie Betts has found inspiration shooting on battlefields of all stripes. “For me, it’s like almost traveling back in time. I’ve been lucky and have had most of the battlefields all to myself when shooting. The silence and stillness is such a contrast to what was occurring during the battle. Some still have the look of a battlefield, with incredible earthworks, while others are completely developed commercial or residential areas.”

If you're interested in donating your time and talent for the American Battlefield Trust or taking high resolution photography for Hallowed Ground, please send an email with a web link of your work to creative director Jeff Griffith at HallowedGroundPhotography@gmail.com. Please note that images taken at web resolution settings or on most mobile phones are not of suitably high resolution to reproduce in print media.