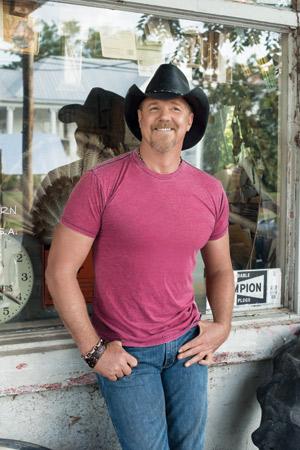

Trace Adkins

Growing up in Sarepta, La., and now living near Nashville, Tenn., I have spent much of my life surrounded by Civil War battlefields. My interest in the Civil War grew out of a conversation I had with my grandfather when I was 13 years old, during which he told me the story of my great-great-grandfather, Henry T. Morgan. Henry Morgan was a private in the 31st Louisiana Infantry. He was wounded and taken prisoner at Vicksburg in 1863.

Subsequently, I have been fortunate enough to be able to visit Vicksburg National Military Park multiple times. During my first visit to Vicksburg, I got to stand where I knew I was within 100 feet or so of where my great-great-grandfather was positioned in that battle. Because of the preservation of that battlefield, I was able to look across the battlefield and see it the way it looked when my great-great-grandfather was there. Words cannot describe what a spiritual moment that was for me, and it was only possible because of the preservation of that hallowed ground.

The seriousness of the threat to these unique resources was truly brought home to me one winter day while I was stuck in traffic on Interstate 65 in middle Tennessee. I looked out the window of my truck and realized that I was stopped within sight of Overton Hill, site of a major Union attack during the Battle of Nashville in December 1864. Today, the hill is occupied by a high school, a football stadium and a smattering of small businesses.

As I was sitting in my truck, I realized that it was December 15, the anniversary of the Battle of Nashville. I wondered what would happen if I went walking up and down the backed-up interstate, knocking on car windows. If I asked them what happened on that hill, on that very day almost 150 years ago, could they tell me? Sadly, I was forced to admit to myself that there likely was not a car within a half mile with an occupant who could recite the story of what happened there. Writing of Overton Hill after the battle in December 1864, somebody wrote that you could walk from the bottom of the hill to the top without putting your foot on the ground — that you could walk on soldiers’ bodies up that hill. Blood was literally flowing down that hill on the morning of December 15, 1864.

It was then that I realized the importance of preserving Civil War battlegrounds — now, before they are paved over and forgotten. The difference between a battle that is written about and taught to our children and one that is largely forgotten can be summed up in one word — preservation. Contrast Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg and a similar frontal assault at Franklin, Tenn., near where I live. Franklin had twice as many casualties, lasted two or three times as long and the attackers went twice as far against much greater odds. Yet, we remember and hear more about Pickett’s Charge, which is in a national park, than Franklin, which was paved over.

The protection of America’s remaining Civil War battlefields will leave a legacy of national commitment to preservation and conservation. In their natural and pristine state they offer a way to connect to the experience of our Civil War ancestors. As I learned at Vicksburg National Military Park, this experience is unlike anything you can read in a book. Preserved battlefields are a legacy we will leave for future generations – a tangible link to the history that defined our nation. As a descendant of a Civil War soldier, I can think of no better tribute during the 150th anniversary of the war than that.