Elizabeth Hobbes Keckley

Virginia

Rte 1 (N of Sappony Creek)

Dewitt, VA 23840

United States

This heritage site is a part of the American Battlefield Trust's Road to Freedom Tour Guide app, which showcases sites integral to the Black experience during the Civil War era. Download the FREE app now.

“No one who ever saw her, or had any contact with her, even casually, would ever be likely to forget her,” said Reverend Francis Grimké about Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley (1818-1907), or Keckly, after her death in 1907. Before and during the Civil War, Keckley was a dressmaker to the nation’s elites – including First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln – who built a formidable sphere of influence in Washington society.

Early Life

Keckley was born into slavery near here in Dinwiddie County in 1818. Her mother, Aggy Hobbs, was enslaved by Keckley’s biological father, Armistead Burwell. Keckley’s mother taught her to sew as part of the domestic duties they were compelled to perform for the Burwells. In her memoir, Keckley recalled the decades of pain and violence she experienced in bondage. One such memory was the separation from the man she considered her father – her mother’s husband, George – when she was a child. The family that enslaved George moved out of state and she never saw him again.

When she was fourteen, the Burwells sent Keckley to North Carolina. She was assaulted by a local store owner there for years and had a son in 1839. Keckley was later forced to relocate again to St. Louis where she worked as a seamstress. She quickly earned regular customers and a prominent reputation with her talents in dressmaking. Though her wages went to her enslavers, Keckley was determined to be free. By 1855, Keckley had raised the money to purchase her and her son’s freedom and she began her own business. After moving to Washington, D.C. in 1860, Keckley’s designs gained the attention of many women in elite circles, including the incoming first lady, Mary Todd Lincoln.

Civil War

Keckley became a prominent figure in the White House during the Lincoln presidency and was the preferred dressmaker for and confidante of the First Lady throughout the war. Both women grieved sons early in their relationship. Keckley’s only son George, passing as a white man, enlisted in the Union army and was killed at the 1861 Battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri. The following year, the Lincolns lost their young son, Willie, to illness.

Keckley used her influence in Washington to support relief efforts for men, women, and children who escaped slavery – or “contrabands” – and sought safety in the nation’s capital. She founded the Contraband Relief Association and worked closely with other prominent leaders, such as Frederick Douglass, on behalf of freedpeople.

Legacy

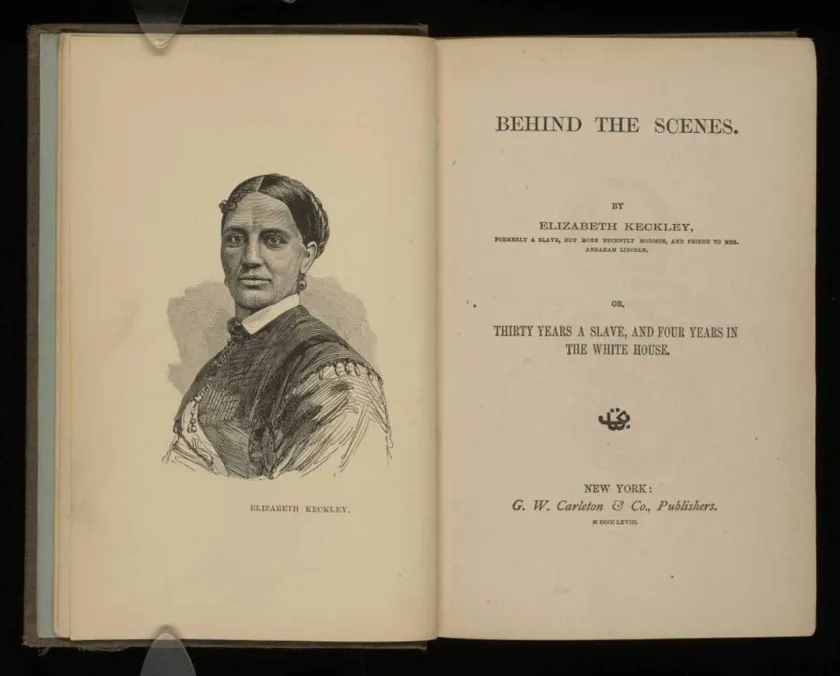

Following the assassination of President Lincoln in April 1865, Keckley and the former First Lady’s relationship faltered. Keckley published a memoir in 1868 entitled Behind the Scenes, Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. Though intended as a positive portrayal of the former First Lady, Keckley’s memoir was criticized by both the press and Lincoln herself for revealing private details to the public. Despite this backlash, Keckley continued to work as a dressmaker and trained other Black women as seamstresses. She later served as the head of the Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts at Wilberforce University in Ohio. Keckley eventually returned to Washington, where she died in 1907 at the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children, an organization her philanthropic activities helped create.

Keckley’s success as a dressmaker left a lasting impact on American fashion and culture, and she paved the way for future generations of Black businesswomen and designers. Though Keckley’s memoir was controversial in her lifetime, many historians consider the book an invaluable firsthand account of the Lincoln White House that has significantly influenced our understanding of the wartime years.

Marker: S-85, Virginia Department of Historic Resources (2011)