Freedman's Village

Virginia

801 S Oak St

Arlington, VA 22204

United States

This heritage site is a part of the American Battlefield Trust's Road to Freedom Tour Guide app, which showcases sites integral to the Black experience during the Civil War era. Download the FREE app now.

This land in front of you – now part of Arlington National Cemetery – was once the site of a community known as Freedman’s Village. Amongst the houses, churches, schools, and other structures that stood here, formerly enslaved Black men and women built new lives and opportunities for themselves as free citizens.

During the Civil War, refugees from slavery surged into Washington, D.C. Thousands of men, women, and children who escaped bondage sought safety, work, and the chance toreunite with loved ones in the nation’s capital. The government erected camps to accommodate refugees, but these sparse sites quickly became crowded and unsanitary. To help alleviate these terrible conditions in the city, representatives ofthe War Department and the American Missionary Association selected Arlington Heights in Virginia as the site for a new community for freedpeople. The intentionally symbolic location – the former plantation of Confederate general Robert E. Lee by way of marriage – put the community in the national spotlight. Freedman’s Village was formally dedicated in 1863.

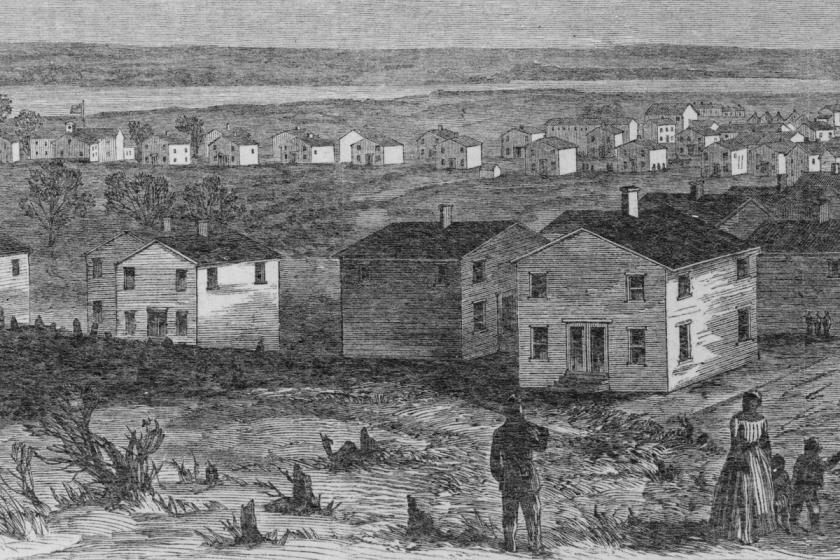

![Freedmans Village near Arlington Hights, Va., July 10th, 1865. Genl. [ground] Plan No. 9.](/sites/default/files/styles/wysiwyg_75/public/freedmans-village-loc-3.jpg?itok=o10nyFDu)

The federal government envisioned this new village as a “model” community where adults and children would temporarily live while they learned skilled trades, sought work, and attended school. The 1865 map of Freedman’s Village above shows an expansive, orderly plan that included fifty 1.5-story houses, schools, a hospital, a home for the aged and infirm, and a church. You may note the streets and parks on the site plan are named after well-known politicians and military leaders. This is a more literal reminder that the Village, though established for freedpeople, was managed by the federal government. Villagers were often subject to white government officials’ strict supervision, political priorities, and paternalistic policies.

Yet, both during and after the war, generations of Black residents advocated for their right to forge Freedman’s Village into a place that they could call home. The population grew quickly, eventually expanding from just 100 to over one thousand people. Residents sought out and created prospects for shelter, food, medical care, education, professional training, community support, worship, and political engagement.

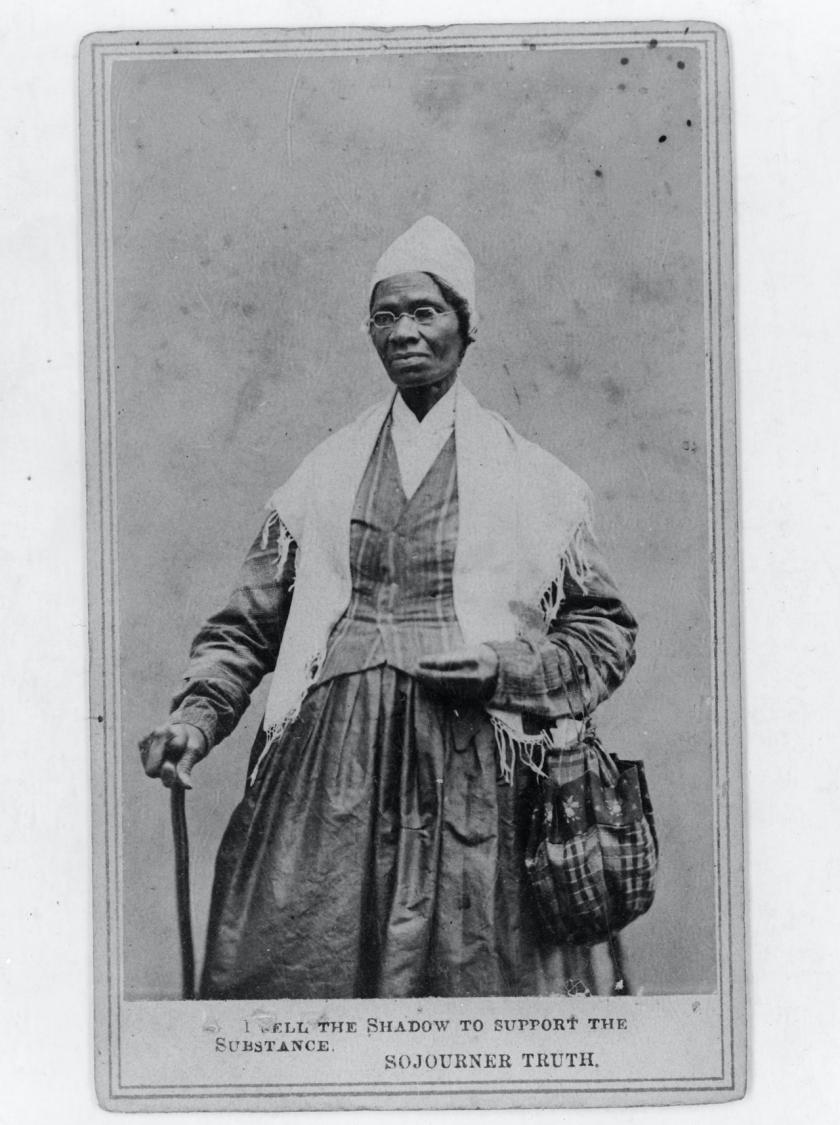

Women had a prominent role in shaping life at Freedman’s Village. One particularly well-known resident was Sojourner Truth, a renowned activist and abolitionist. Truth resided in the village for about one year on behalf of the National Freedman’s Relief Association beginning in 1864. She helped villagers find employment, advised them on their rights, taught women domestic skills, and served as a spiritual mentor.