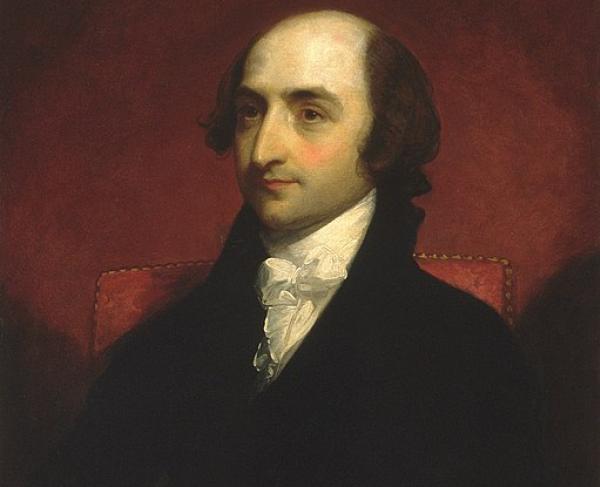

John Gibbon

John Gibbon was born April 20, 1827 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. When he was ten, his father accepted a position as chief assayer at the U.S. Mint in Charlotte, North Carolina and relocated the entire family south. In 1842, Gibbon received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy. His first year was marred by disciplinary problems, and he was forced to repeat it, but his tenure at West Point was thereafter defined by a rigid discipline he would carry through his entire Army career. He graduated in the middle of his class in 1847, the same year as Ambrose Burnside and Ambrose Powell Hill, and was made a second lieutenant of artillery. He served in Mexico (though he did not see combat), in Florida against the Seminole Indians and in Texas before returning to West Point in 1854 to teach artillery tactics. In 1855, he married Francis Moale, and the couple had four children. Gibbon published The Artillerist’s Manual in 1859. The text was widely read and used by both sides during the Civil War.

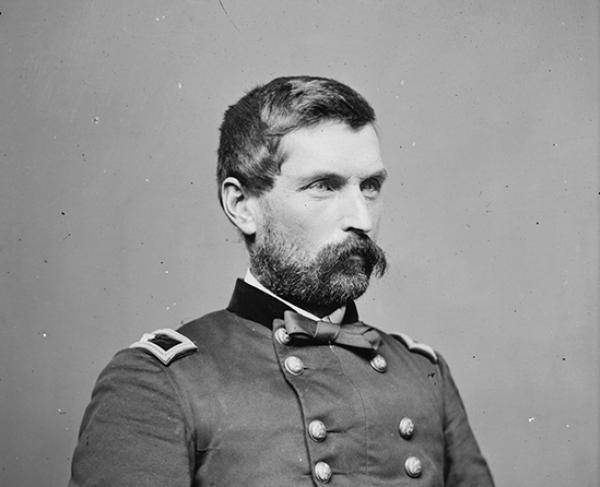

Following the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Gibbon, in spite of the fact that his father was a slaveholder and three of his brothers and his cousin [J. Johnston Pettigrew] went on to fight for the Confederacy, upheld his oath to the United States and reported to Washington for assignment. He was made chief of artillery for Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, and a year later was promoted to brigadier general of Volunteers and placed in command of the “Iron Brigade” of Westerners – Wisconsinites, Michiganders and Indianans. Gibbon made his mark on this illustrious unit, instilling rigid discipline and drilling them into the most tenacious fighters in the Army of the Potomac. He led them at Brawner’s Farm at the Battle of Second Manassas, one of the most intense firefights of entire war, and at Turner’s Gap at the Battle of South Mountain, where Gen. Joseph Hooker gave them their famous nickname.

The Iron Brigade suffered heavy losses fighting in the bloody cornfield at Antietam, where Gibbon himself personally manned an artillery piece. Late in 1862, Gibbon was promoted to command of the 2nd division, I Corps, which he led at Fredericksburg and was wounded. Returning to duty several months later, Gibbon commanded the 2nd Division of the Hancock’s II Corps at Gettysburg, and even directed the corps itself for brief periods during the battle. On July 3, Gibbon’s men, stationed along Cemetery Ridge, played a significant role in the repulse of Pickett’s Charge, and Gibbon was wounded for a second time. During his convalescence, Gibbon attended the dedication of the new national cemetery on November 19 and heard Abraham Lincoln deliver the Gettysburg Address.

By the time of the opening of the Overland Campaign of 1864, Gibbon was back in command of his division and led his men at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, Cold Harbor and the investment of Petersburg. In June, 1864, Gibbon was promoted to Major General and in January of the following year was given command of the XXIV Corps in the Army of the James. Rufus Dawes of the Iron Brigade, on learning of Gibbon’s promotion, wrote “His honors are fairly won. He is one of the bravest of men. He was with us on every battle field.” At the conclusion of the Appomattox campaign that spring, Gibbon served as one of the surrender commissioners when the Army of Northern Virginia finally succumbed to defeat.

Gibbon remained in the Army until 1891, having served nearly fifty years. In his post-war career, Gibbon, like most regular army men, was primarily engaged with the Indians on the frontier. It was Gibbon’s column who came upon the remains of Custer and his men after Little Big Horn, and Gibbon who led a successful campaign against Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce the following year. He retired in 1891 and moved to Baltimore, where he died on February 6, 1896. Gibbon, who was at the center of many of the most intense fights of the Civil War, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.