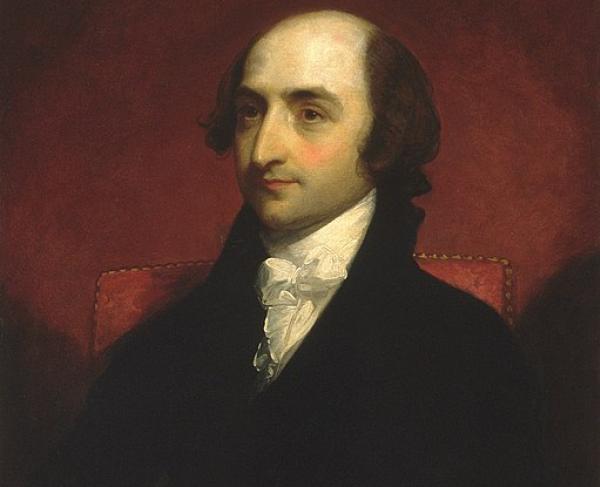

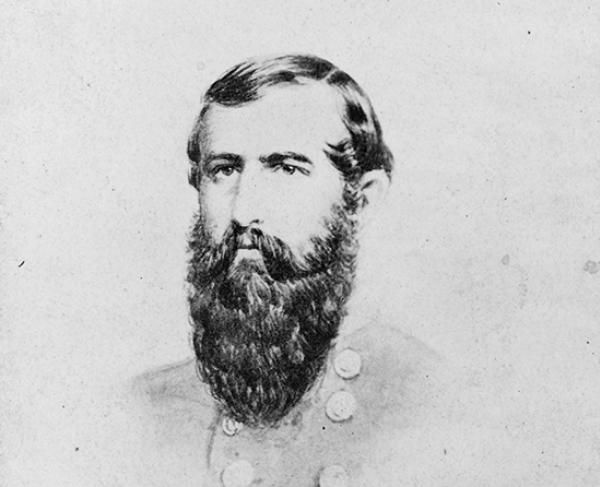

John C. Pemberton

Born a Union man in Philadelphia in August of 1814, John Clifford Pemberton would go on to be a quintessential but controversial player in Confederate leadership. As a student at the University of Pennsylvania, the young Pemberton decided he wished to have a career as an engineer. Believing the United States Military Academy the best way gain this education, he applied to West Point, using his family's connection to President Andrew Jackson to secure an appointment. He was admitted to the academy, where he was the roommate and closest friend of George G. Meade. Pemberton graduated near the middle of the class of 1837 before being commissioned as an officer in the 4th Artillery.

Pemberton's antebellum career was typical of many officers of that time. He served in the Second Seminole War in Florida and aided in campaigns against the Cherokees in the west before serving under Zachary Taylor during the Mexican war. After the war, Pemberton married a Virginian, Martha Thompson. In the absence of any record of his thoughts on states' rights or slavery, many historians have come to believe Pemberton's marriage to this Norfolk native was the primary reason he sided with the Confederacy. With the secession of his wife's home state in 1861, Pemberton resigned from the Federal army and in June of that same year was made a brigadier general in the Confederate Army.

Pemberton's early service in the Confederacy constituted primarily of strengthening coastal defenses in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. Due to his Yankee background, however, the general's relationships with local governors left much to be desired and Pemberton was transferred west. In October of 1862 he was promoted to lieutenant general and assigned command of the District of Mississippi and East Louisiana.

At the heart of this district was the vital shipping port of Vicksburg. With orders to hold the city at all costs, Pemberton expended a great deal of energy revamping its defenses, as well as improving defenses along the Mississippi River. In spite of these efforts—and Union defeats at Holly Springs and Chicksaw Bluffs—there was little Pemberton could do in the face of the impending Union attack on Vicksburg. To make matters worse, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston reassigned Pemberton's cavalry to the Army of Tennessee. Thus, in May of 1863, when Union General Ulysses S. Grant's campaign to take the city began in earnest, the Confederate defender was deprived of vital intelligence about his enemy's whereabouts. Poor communication and lack of coordination with Johnston—as well as the Pemberton's own tactical errors—led to Confederate defeats at Champion Hill and Big Black River Bridge, and Pemberton was forced to back into the Vicksburg defenses. Two failed attempts to take the city by direct assault demonstrated the strength of the Vicksburg defenses and compelled Grant to lay siege to the city. Despite constant pleas to Johnston for aid, Pemberton was completely isolated. Eventually, lack of supplies and starvation took their toll. On July 4, 1863, after 46 days, Pemberton surrendered 2,166 officers and 27,230 men, 172 cannon, and almost 60,000 muskets and rifles to the Federals.

Branded a traitor by Southerners for surrendering Vicksburg, Pemberton spent the remainder of 1863 the spring of 1864 in Virginia, an officer without a command. Boredom and a desire to render faithful service to his adopted country prompted the former Northerner to write President Jefferson Davis for an assignment. Unable to procure a position commensurate with his rank, Pemberton resigned his general's commission and made a lieutenant colonel of artillery. After commanding the Richmond Defense Battalion, he was made inspector general of ordinance before the surrender of the Confederate Armies in April of 1865.

After the war, Pemberton carried on a feud with Johnston regarding the Vicksburg campaign. He returned to the north in the 1870s and passed away in Philadelphia in 1881 where he is buried.

Related Battles

4,910

32,363