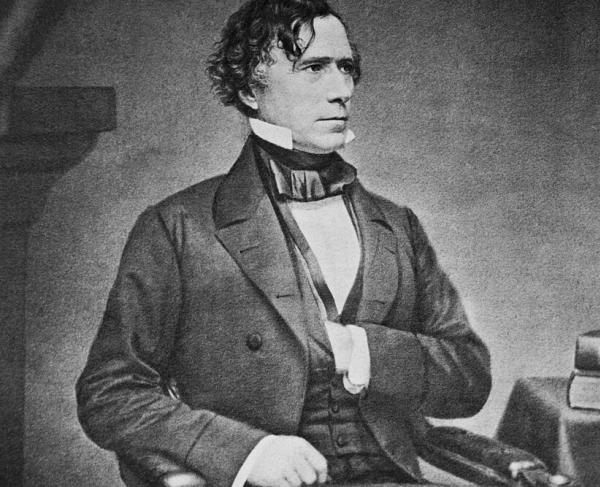

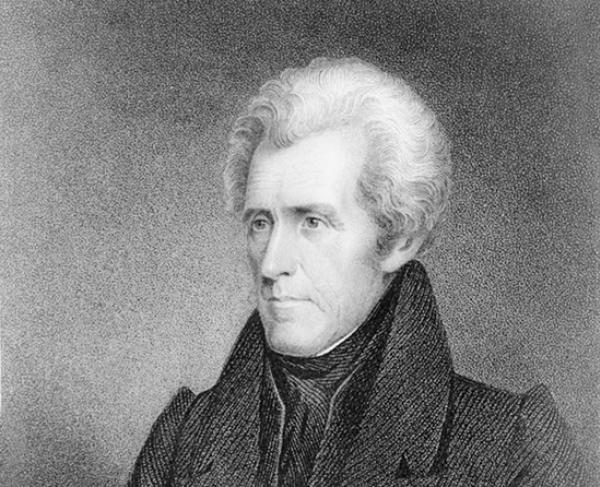

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson served as the 7th President of the United States. Before his Presidential term, Jackson was a celebrated military commander who led American troops during The Creek War of 1813-14, War of 1812 and First Seminole War. Known as a populist candidate and revered military leader in his time, Andrew Jackson’s complicated life tells us much about warfare and politics in the United States during the early nineteenth century.

Andrew Jackson was born on the border of North and South Carolina on March 15, 1767. He was the third son of Andrew and Elizabeth Jackson. His father died shortly before his birth. Jackson grew up in the Waxhaws settlement, previously occupied by the Waxhaw people who were decimated by European diseases. The settlement was home to Irish, Scots-Irish, and German settlers.

Only a young boy during the Revolution, Jackson lived through the British invasion of the western Carolinas in 1780-81. The British captured Charleston on May 12, 1780. Following the capture of Charleston, groups of soldiers and Tory sympathizers pillaged the South Carolina countryside. British forces surprised American forces at the Waxhaw’s settlement where the Jacksons lived, killing over 100 soldiers and destroying the settlement. Many survivors of the battle claimed the British massacred patriots who were surrendering. The massacre at Waxhaw’s, also called Buford's Massacre, sparked outrage throughout the colonies. Soon after Andrew and his brothers joined a patriot regiment.

Andrew Jackson served as a courier for the Continental Army and was captured and imprisoned by the British in 1781. He witnessed the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill as a British prisoner of war. While in captivity Jackson suffered greatly, nearly starving, contracting smallpox, and being slashed with a sword by a British officer for refusing to clean his boots.

Jackson lost many family members during the Revolutionary War. His older brother died of heatstroke at the Battle of Stono Ferry in 1781, and his younger brother died of smallpox after being released from British imprisonment. His mother, Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, died that same year of cholera after nursing American prisoners in Charleston Harbor. By age 14, Andrew Jackson was an orphan, hardened by warfare, with a thorough hatred for the British.

After the Revolution, he began a legal and political career in Tennessee, serving in the Tennessee Constitutional Convention in 1796. Jackson’s legal practice prospered enough for him to build a mansion and purchase enslaved people to work on the plantation. This home, called the Hermitage, is where Jackson lived with his wife Rachel. Today it is preserved as a museum today outside of Nashville, TN.

In 1796, Jackson became the first man elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. He served in the US Senate for a brief time, gaining prominence in Tennessee and national politics.

He returned to military service in 1812 as a Major General in the Tennessee Militia during the Creek War. Conflict with the Creek Nation stemmed from American settlers encroaching on their land in Georgia and Alabama. The treaties made with settlers split the tribe into factions who either resisted or accepted this expansion. On August 30, 1813, a militant group of Creeks, known as Red Sticks, attacked Fort Mims in Alabama and killed all its inhabitants. Tennessee Governor Willie Blount ordered Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson to suppress the Red Sticks. Throughout November 1813, Jackson led the main effort against the Red Sticks by attacking Creek towns. During the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on March 27, 1814, U.S. forces inflicted 75% casualties on the Red Sticks, leading to their surrender in August of 1814. The remaining Red Sticks fled to Spanish Florida, and Jackson was promoted to Major General in the Regular Army. The Treaty that ended this conflict had later implications for President Jackson’s treatment of Native Americans and the Trail of Tears.

Following this, Jackson was promoted to Major General in the Regular Army. As the War of 1812 continued, the British army attacked and burned Washington D.C. in August 1814. Their focus then shifted to New Orleans, a vital port city in the south. Andrew Jackson mobilized his forces in Mobile, Alabama to beat the British to New Orleans. He arrived on December 1 and assembled an army of Tennessee and Kentucky frontiersmen, Louisiana militia, New Orleans businessmen, Free Men of Color, Choctaw Indians, privateers, sailors, and other U.S. troops. During the Battle of New Orleans Jackson led the American forces to a decisive victory against the British on January 8, 1815. News of the Treaty of Ghent, signed abroad in December 1814, signified the end of the war. After the Battle of New Orleans, Jackson earned the nickname “Old Hickory,” in reference to his strength and determination.

After the War of 1812, Jackson served in the First Seminole War, invading Spanish Florida and forcing a peace treaty. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun gave Jackson command to quell uprisings of Seminole Indians against settlers. Jackson strategized that the best way to maintain control was to seize Florida from the Spanish. He invaded Florida on May 24, 1818. Because the United States never officially declared war on Spain, Jackson was censured by Calhoun and others in Congress for violating the constitution. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams supported Jackson, saying that the invasion would motivate Spain to sell the territory to the United States, which it did in 1819.

Because of his national recognition and military record, Jackson was nominated for the Presidency in 1822 as the Republican candidate and elected as a Senator again in 1824. Jackson won the hotly contested election of 1828, defeating John Quincy Adams, to become the 7th President of the United States. As a candidate, Jackson was bolstered by his military achievements and persona as a man of the people from humble beginnings.

In 1830, President Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which established a process for the president to exchange land west of the Mississippi for Indian lands in the east. Although some tribes elected to move west, the U.S. government also bribed and threatened tribes into signing removal treaties. Subsequent treaties forged because of the act led to the forcible relocation of tens of thousands of Native Americans in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama. In his address to Congress on the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Jackson asserted that the relocation of Native Americans would “enable those states to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power.” Throughout Jackson’s presidency he negotiated almost 70 removal treaties, which led to the relocation of around 50,000 Native Americans to land in what is now Oklahoma. The Trail of Tears refers to the forced relocation of Native Americans in the 1830s, on which some had to walk over 1,000 miles over four months. Approximately 4,000 of the 16,000 Cherokees perished along the way.

During his presidency, Jackson wanted the government to work for the common man. He prioritized decentralizing the national bank system and reforming currency, both of which helped to produce an economic downtown in the years to follow. Jackson served two terms, ending in 1837. After his Presidency, Jackson returned to his plantation, the Hermitage, where he died in 1845.