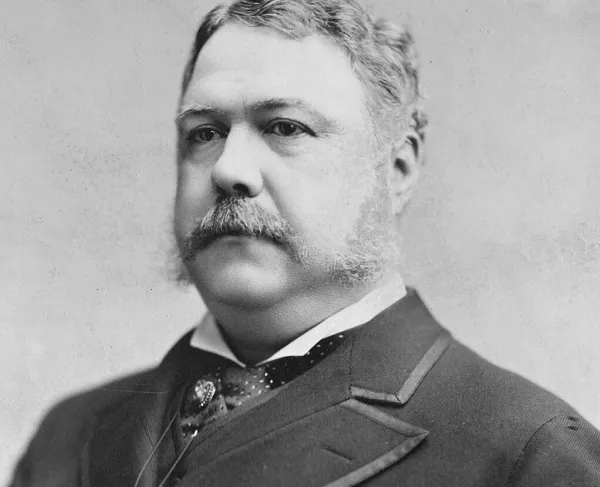

Chester A. Arthur

Born on October 5, 1829, in Fairfield, Vermont, Chester A. Arthur was the fifth of nine children. His parents—William and Malvina Arthur—moved to many villages in New England and New York during his childhood since his father held different pastoral positions in the Baptist church and advocated for the abolition of slavery. Young Arthur showed interest in American politics during his school years, getting into a schoolyard fight over the candidates of the 1844 presidential election.

By 1845, Arthur had completed his preparatory education and entered Union college. He graduated in 1848 and became a teacher to pay for his law school education. Five years later, he had saved enough money to move to New York City and read law. Arthur was admitted to the New York bar in 1854 and joined a law firm.

Arthur worked on cases that challenged slavery and pushed for civil rights; one of his early cases led to the verdict which prompted the desegregation of street cars in New York City. With a new law partner, Arthur travelled to Kansas Territory, hoping to settle, start a law practice and support the anti-slavery partisans. He quickly decided the territory was not the place for him, returning to New York. Arthur married Ellen Hernon in 1859, and the couple had three children—two surviving to adulthood. To support his family, he focused on his law practice and also took part in politics with the new Republican Party.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, the New York governor appointed Arthur to his staff as engineer-in-chief—a patronage position. Efficient and organized, Arthur promoted to brigadier general and served in the state militia’s quartermaster department. The following year he became inspector general for New York’s state militia and then the state’s quartermaster general, organizing supplies and bringing order to volunteers enlisting to fight for the Union. Several times the governor asked Arthur to turn down field command and remain at his appointed post. Arthur did travel to Fredericksburg, Virginia, during the spring of 1862 to visit Union soldiers. Despite his recognized work as a recruiter and quartermaster, he was relieved of military duties in 1863 when a new governor took office—the challenge of a political patronage position. Arthur petitioned to return to his military duties, but his offer was turned down.

He focused on his law practice and networking with political leaders he met during his war service. Arthur also campaigned and fundraised for President Lincoln and the Republican Party during the 1864 election, stepping into the conservative Republican political faction and machine in New York’s political scene. By 1868, he was chairman of the New York City Republican executive committee, and he coordinated fundraising to support Ulysses S. Grant’s presidential campaign and working against Tammany Hall.

President Grant nominated Arthur as the Collector of the Port of New York, a position in the Custom House which oversaw nearly one thousand jobs and had high compensation. A few years later when Rutherford B. Hayes became president, Hayes promised to reform the patronage system of government positions. Arthur was asked to resign as part of the reforms; when he refused, Hayes eventually fired him but offered him a diplomatic post in Paris, France, which Arthur declined. With his new free time, Arthur became chairman of the New York State Republican Executive Committee, helping to strategize and win elected seats for other political characters.

Arthur’s year of 1880 had tragedy and triumph. His wife died unexpectedly in January, bringing devastating grief to Arthur and their children. Later in the year, Republicans approached him, gauging his interest in running for vice president on James Garfield’s presidential ticket. Surprised to be asked, Arthur agreed to run as vice president, and campaigners promoted that both Garfield and Arthur were Union veterans committed to keeping the political outcomes of the war. The election was close, but in the end, Garfield won the presidency and his opponent—Winfield S. Hancock—graciously conceded.

As vice president, Arthur disagreed with Garfield’s approach to political patronage and handling of Republican party factions. By inauguration day in 1881, many people considered the president and vice president politically estranged. Still, Vice President Arthur had a key role; since the Senate was nearly politically tied on votes, he would have the consequential tie-breaking vote on bills and nominations. Congress was out of session during the summer of 1881, and Arthur traveled to New York. There, on July 2, he received a message that President Garfield had been shot by an assassin. For the following two months, Arthur hesitated to assume the executive role while Garfield was still living, but on September 19, 1881, Garfield died. Chester Arthur took the oath of office at his home the following morning, becoming the twenty-first President of the United States. (His sister, Mary Arthur McElroy, filled the role of hostess at the White House for social occasions since Arthur was a widower.)

Arthur’s administration surprised and pleased many Americans; he showed executive power, pushing back on his political party’s agenda and at times asking Congress to revise legislation. In both domestic and foreign policy, he made changes and sought reforms when possible.

Notably, Arthur supported bi-partisan efforts for civil service reform; in January 1883, he signed into law the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act and quickly appointed members for the Civil Service Commission which would prepare job position evaluations and rules, particularly that jobs in the postal service and custom houses should be given according to merit. The new system created a classified system—making government jobs obtainable only through competitive examinations—and protected government employees from job position or loss for political reasons.

He attempted to support civil rights for African Americans, trying to form political coalitions and speaking against court rules and congressional inaction that limited protections. Arthur pressured Congress to increase funding for Native American education and to allow more land ownership, though not always understanding the harsh realities of the situations Indigenous people faced.

With foreign policy, Arthur’s administration made efforts to increase trade between nations in the Western Hemisphere. Arthur signed the Tariff Act of 1883, trying to lower tariff rates to balance the government’s annual revenue surplus. This effort went against his political party’s preferences and was an effort to shape policy as president outside of party politics. Ultimately, this decision and guidance brought tariffs and tariff rates back to a centerstage political issue in the future elections. He forced also Congress to revise immigration bills before he signed them, and initially vetoed the extension of Chinese Exclusion Act, though he eventually signed a compromise measure. Arthur strongly supported reforms to strengthen and modernize of the U.S. Navy.

A short time after taking office, Arthur’s doctors diagnosed him with a kidney disease. He kept his illness private, but rumors circulated especially as his appearance and energy changed. His health along with realizing the lack of support from the divided Republican Party prompted Arthur decide against strongly seeking nomination for the 1884 presidential election. As a result James G. Blaine ran for office on the Republican ticket, losing to Grover Cleveland.

Chester Arthur died suddenly on November 18, 1886, and was buried in Albany, New York, among Civil War veterans.