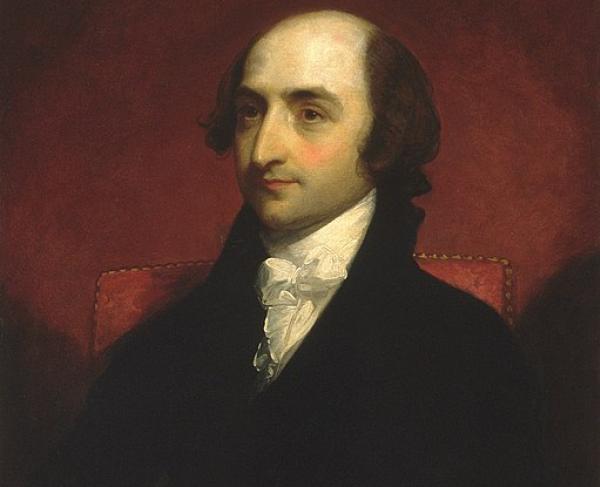

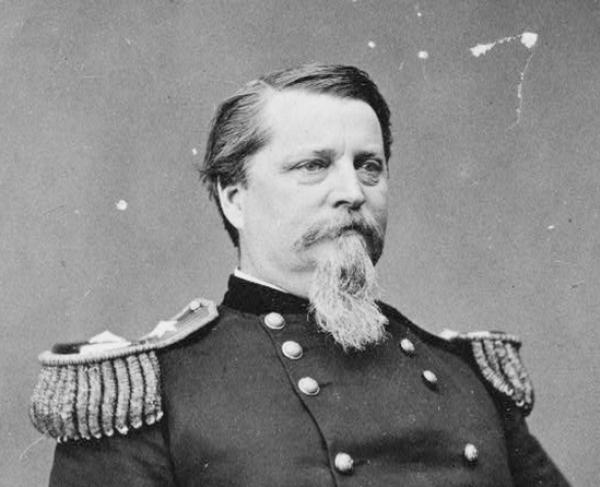

Winfield Scott Hancock

“General Hancock is one of the handsomest men in the United States Army,” wrote Regis de Trobiand in July 1864. “He is tall in stature, robust in figure, with movements of easy dignity … In action … dignity gives way to activity; his features become animated, his voice loud, his eyes are on fire, his blood kindles, and his bearing is that of a man carried away by passion – the character of his bravery” (Tucker 246-247). Winfield Scott Hancock impressed his superiors and his soldiers alike. After the Battle of Williamsburg, General George B. McClellan wrote to his wife, “Hancock was superb today.” “Superb” stuck with him throughout the war. However, like many other great Civil War leaders, the public’s high regard disintegrated after the war. Today he is highly esteemed again, with memorials such as the renaming of the courthouse square in his old home town, “General Winfield Scott Hancock Square.”

Hancock graduated from West Point in 1844, 18th in a class of 25. He served in the Mexican War and was honored for his bravery at the battle of Churubusco. When the war began he was serving at Los Angeles, struggling to keep Union ammunition from Southern sympathizers. He was assigned to be General Robert Anderson’s quartermaster in Kentucky. Thankfully for the Union, Gen. McClellan recognized Hancock’s potential and made him a Brigadier General in William “Baldy” Smith’s Division.

On May 5, 1862, Hancock took the initiative in the Battle of Williamsburg and occupied two abandoned redoubts. Despite an overall Union loss, Hancock’s reputation skyrocketed because of this battle. During the September 17, 1862 Battle of Antietam, Hancock was ordered to command mortally wounded Gen. Israel Richardson’s division at the sunken Road. In November he was promoted to Major General.

At Chancellorsville, May 1-3, 1863; Hancock’s division was the last on the field, holding on long enough for the Federals to withdraw. General Darius Couch, commander of the Union Second Corps, had been extremely disgusted with the performance of Gen. “Fighting Joe” Hooker. Couch left the corps and Hancock became its new commander. By the July 1-3, 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, George Gordon Meade was the new commanding general. After learning that the armies were engaged at Gettysburg and Gen. John Reynolds was killed, Meade sent Hancock to command the 1st, 3rd and 11th corps and decide if this was a good battle position. On July 2nd Hancock helped fix Gen. Daniel Sickle’s blunder at the Peach Orchard, he also sent the 1st Minnesota to halt Gen. A.P. Hill’s corps at Cemetery Ridge. On the 3rd, his men helped beat back “Pickett’s Charge” Hancock was seriously wounded in the thigh during the battle, and General Gouverneur Warren took command of the Second Corps. Hancock spent months in excruciating pain while several doctors attempted to remove the minié ball. A Joint Resolution of Congress was passed on January 28, 1864 thanking Generals Meade, Hooker and Howard for their roles at Gettysburg. Hancock’s name was absent.

By the time Hancock rejoined the Second Corps in March, Ulysses S. Grant was the commander of all Union forces. Under Grant the Union’s style of fighting had changed significantly. Even though the Federals lost the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5-7, 1864 they did not retreat. Hancock’s Second Corps attacked A.P. Hill’s corps at the Plank Road, driving the Confederates back in confusion. Gen. James Longstreet’s arrival prevented the Confederate right flank from collapsing.

At Spotsylvania Courthouse, Hancock’s men successfully attacked the “Mule Shoe Salient” on May 12, 1864 and captured approximately 2800 prisoners. Hancock’s men also took part in the infamous June 3rd attacks at Cold Harbor, in which thousands of men were lost in minutes. By June 10th, his Gettysburg wound had left him immobilized. A tremendous opportunity was lost at Petersburg, July 15-18, 1864. On June 15th, General “Baldy” Smith’s forces defeated a small Confederate force three miles east of the primary defensive line. Had Hancock taken command as the ranking officer, and ordered another charge, Union forces might have prevailed.

On July 27th, Hancock’s Second Corps coordinated with Philip Sheridan’s cavalry, crossing north of the James River at Deep Bottom in an attempt to sever the railroad lines linking Lee and Jubal Early (in the Shenandoah Valley). He fell short of his goal, breaking only the outer Confederate lines. There was a second fight at Deep Bottom; however, due to the heat and the high number of new recruits, the battle was lost. This loss was followed by a humiliating defeat at Reams Station, August 24, 1864. Hancock’s adjutant recalled that “the agony of that day never passed away from the proud soldier” (Jordan 163). At Burgess Mill, October 27-28, 1864, the Second Corps performed well, but gained and then lost the Boydton Plank Road. This was Hancock’s last battle. He went on to head the Department of West Virginia until war’s end, and also organized the 1st Veterans Corp.

After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Hancock received criticism for his role in the execution of Mary Surratt, one of the conspirators. He did not want Surratt to be executed. He also received criticism while commander of the Fifth Military District during Reconstruction. He had issued “General Orders No. 40”, declaring that a state of peace existed in the district so he would not interfere with civil authorities. This also meant that no soldiers would appear at polling places.

When Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president, Hancock was sent to the Department of Dakota. When George Meade died in November 1872, Hancock became the new Commander of the Division of the Atlantic, a position he held for the rest of his life. In 1880, Hancock was the Democratic presidential candidate. He was defeated by James A. Garfield. On February 9th 1886, Winfield Hancock died due to complications from diabetes. He was laid to rest at Norristown, PA.

Further Reading

- Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life By: David M. Jordan

- Hancock the Superb By: Glenn Tucker