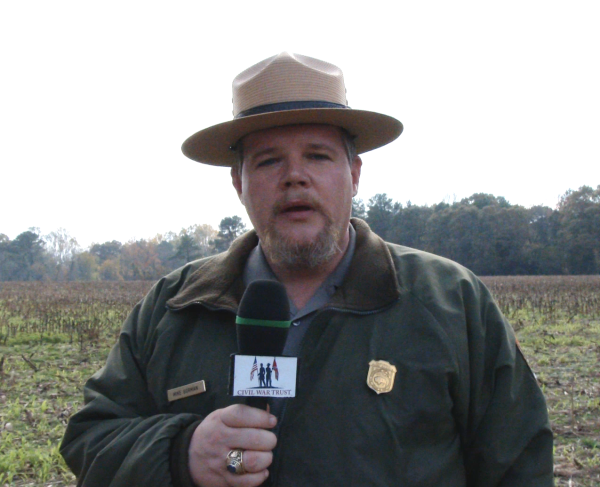

Cold Harbor

Hanover County, VA | May 31 - Jun 12, 1864

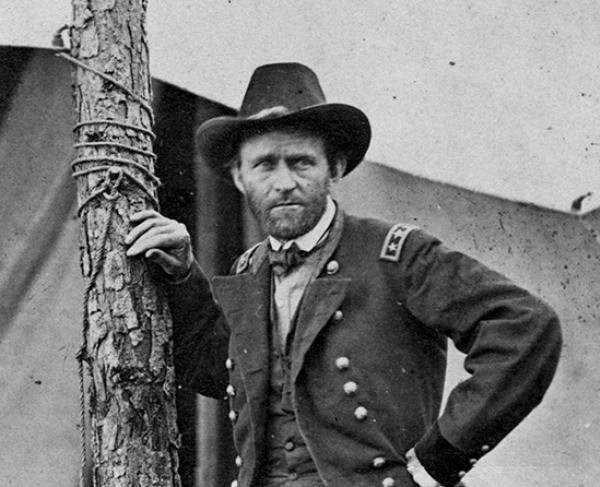

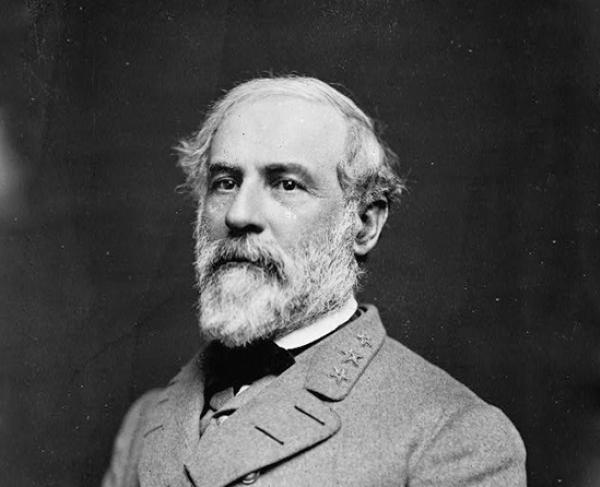

As Union forces advanced toward Richmond in the spring of 1864, Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army repulsed and outmaneuvered Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s troops at Cold Harbor in a devastating two-week action that cost more than 17,000 lives.

How it ended

Confederate victory. The Union failed to penetrate Confederate defenses in a fierce fight. Despite the staggering losses at Cold Harbor, Grant managed to withdraw his troops and then deceive the Confederates for days as his army stealthily crossed the James River and marched towards Petersburg.

In context

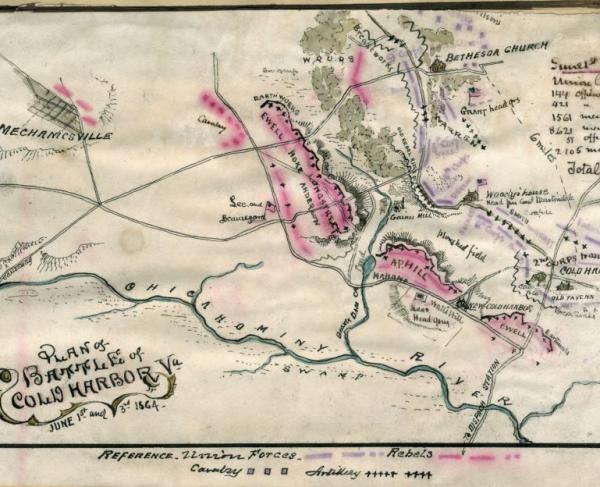

In the summer of 1864, the Union Army of the Potomac was fighting its way south toward Richmond, Virginia. In a series of battles collectively known as the Overland Campaign, the Federals had suffered more than 50,000 casualties but had also forced Robert E. Lee’s Confederate veterans to abandon much of northern Virginia. The small crossroads of Cold Harbor, just 10 miles north of Richmond, became the focal point of the action in late May. From May 31–June 3, Ulysses S. Grant ordered repeated attacks against entrenched Confederate positions, culminating in an enormously bloody repulse on June 3. Both armies held their ground and kept up a withering fire between the lines until June 12, at which point Grant withdrew but continued to move east and south. The Army of the Potomac crossed the James River and, by June 16, was in position to directly threaten the manufacturing and rail center of Petersburg—a critical gateway to Richmond.

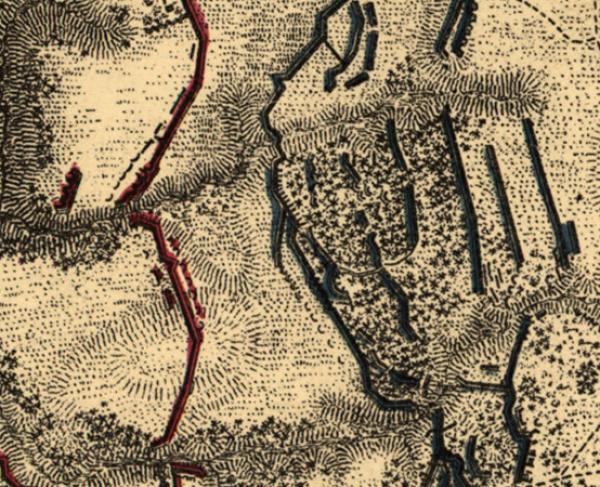

After two days of inconclusive fighting from May 28 to May 30 at Totopotomoy Creek, Lee and Grant order their troops to move toward Cold Harbor. The roads emanating through this critical junction lead to Richmond and to supply and reinforcement sources for the Union army. Philip Sheridan's Union cavalry is instructed to capture the strategic crossroads.

May 31. After a sharp contest with Confederate cavalry under Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, Sheridan’s troops seize the intersection. The Confederate cavalry are soon joined by the infantry of Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke's division. After a short battle, Union cavalry drive the Confederates beyond the crossroads where they begin to build defensive trenches. Hearing reports that Lee is extending his line to the James River, Grant is determined to extend his left flank, overpower Lee, and come between the Confederates and Richmond, all while keeping access to the James River open.

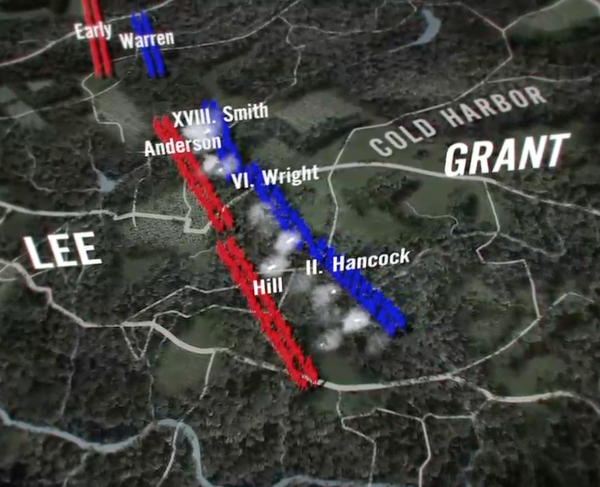

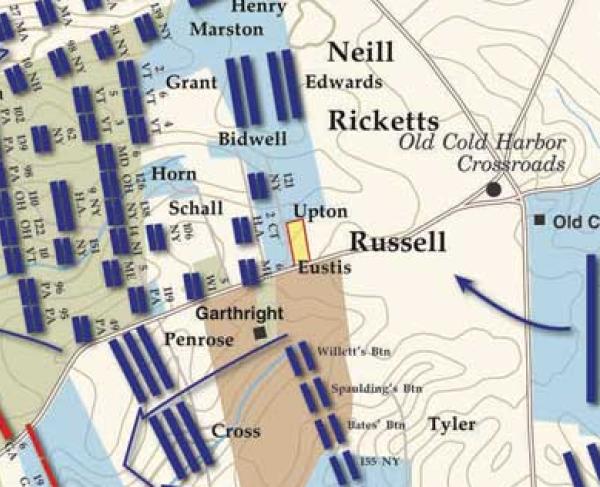

June 1. That morning, Sheridan beats back a half-hearted attack by Hoke’s and Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw's divisions. Encouraged by this success, Grant orders Maj. Gen. William "Baldy" Smith’s Eighteenth Corps and Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s Sixth Corps to relieve Sheridan and strike the Confederate defenses that same day. However, confused orders and bad roads slow the movement of the two Federal corps; Grant’s impromptu attack is delayed until 5:00 p.m. A brigade from Wright’s corps briefly breaks through the Confederate line, only to be pushed back by a counterattack. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade orders Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps to march 12 miles overnight to provide support for another assault.

June 2. Meade orders an early morning attack, but Smith objects, citing the “absence of any military plan.” Hancock’s Second Corps, which got lost during the night march, does not arrive until about 6:30 a.m., persuading Meade to postpone the attack until 5:00 p.m. that day. Grant, concerned that Hancock’s men will be too tired for action, advises Meade to wait until June 3. Lee takes advantage of this delay and orders his troops to construct an impressive and intricate series of entrenchments, which reinforces his position in the heavily wooded and uneven terrain.

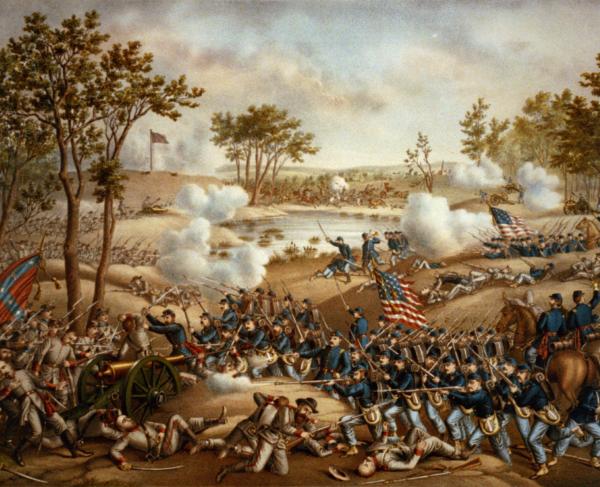

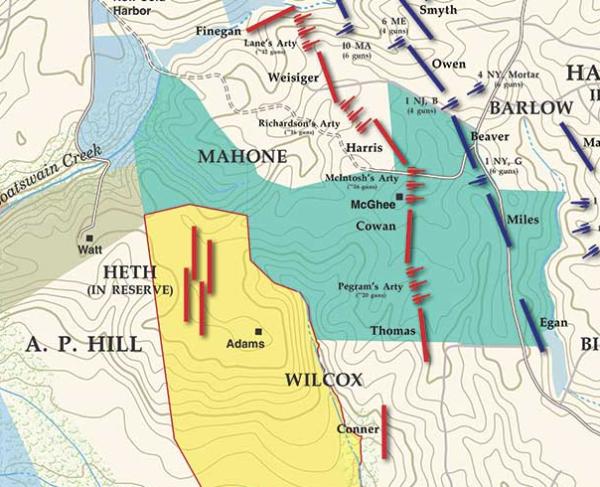

June 3. At 4:30 a.m., the Second, Sixth, and Eighteenth Corps launch the main attack through the darkness and fog. The soldiers soon become caught in the swamps, ravines, and heavy vegetation, losing contact with each other. Angles in the Confederate works allow Lee’s men to easily enfilade the Federal ranks as they advance. An estimated 7,000 men are killed or wounded within the first 30 minutes of the assault and the massacre continues through the morning. In Hancock’s sector, elements of the Second Corps manage to seize a portion of the Rebel works only to be bombarded by Confederate artillery that turns the trenches into a deathtrap. Smith’s corps are funneled into two ravines and subsequently mowed down when they reach the Confederates’ position. Pinned down by the tremendous volume of Confederate fire, the remaining Federals dig trenches of their own, sometimes including bodies of dead comrades as part of their improvised earthworks. At 12:30 p.m., after riding the beleaguered Union lines himself, Grant suspends his attack at the advice of the corps commanders.

June 4 to June 12. The days are filled with minor attacks, artillery duels, and sniping. On June 7, Lee and Grant agree to a two-hour truce to allow the Federals a chance to retrieve their wounded. But of the thousands who fell under the brutal summer sun during the past five days, few are found alive.

12,737

4,595

Despite the devastating casualties, Grant plans his next move. He sends Sheridan to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad to the west and on June 12 orders Meade to evacuate Cold Harbor, cross the James River, and proceed toward Petersburg.

Reflecting later on the battle, Grant wrote, "I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made... No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained."

A postponed attack, lax reconnaissance, battle fatigue, and lack of coordination among the commanders, all led to defeat for Grant at Cold Harbor. Grant's decision to postpone the attack on June 2 when Hancock’s troops failed to arrive gave the Confederates time to entrench and strengthen their defenses. And although Grant had directed the Union corps commanders to examine the ground and perfect their plans, they had done neither. They failed to disclose important swamps and other terrain features, and the separate corps did not coordinate with one another. The men were exhausted from the arduous campaign and their ranks were diminished. There was friction between Maj. Gen. Meade and General-in-Chief Grant and the responsibility of who would command the attack was unclear. Grant apparently expected Meade to supervise the assaults, but Meade hung back. The army had no leader. Only the Second Corps and parts of the Eighteenth and Ninth Corps—perhaps twenty thousand Federal troops—were actively engaged.

Grant’s decision to attack on June 3 was an unmitigated disaster. The Federals met with heavy fire and suffered significant casualties. They were only able to reach the Confederate trenches in a few places. A Confederate later described Cold Harbor as "perhaps the easiest victory ever granted to the Confederate arms by the folly of the Federal commanders." One of Meade’s aides described the sad aftermath of the Union failure, during which the opposing armies slept “almost within a stone’s throw of one another,” with “the separating space ploughed by cannon shot, and dotted with dead bodies that neither side dared bury."

The Federals turned the two-story home of Margaret and Miles Garthwright into a field hospital to take in casualties during the battle of Cold Harbor. It was the second time the Garthwrights found their property requisitioned, the first being during the Battle of Gaines’ Mill in 1862. Miles Garthright was a Confederate soldier whose cavalry unit saw action around Cold Harbor early in the battle.

As Union surgeons received maimed soldiers at her home in June 1864, Mrs. Garthright took refuge in the basement, where “with fear and trembling” she watched as blood dripped through the cracks in the floor and into the cellar. Those who survived were transported by rail and steamer to army hospitals in Washington. But many were not that lucky. At least 97 soldiers died from their wounds at Garthwright House and received temporary burial in the front yard. Two years later, the Cold Harbor National Cemetery opened across the road and work crews reburied all of the Union dead there.

Captain Edward Hill of the Sixteenth Michigan Volunteers was shot in action on June 1 at Cold Harbor. His regiment did not expect him to survive. Hill’s experience, documented in the following diary entries, reveals how casualties were handled during the Civil War. The wounded captain was placed on a stretcher and taken to a makeshift field hospital, where he was examined and, according to his friend Private Jack Wood, "left to die." But Hill persevered. Wood arranged for an army wagon to take Hill to White House Landing on the Pamunkey River. Hill suffered excruciating pain on the wagon journey to the wharf at White House, where Wood placed him on a steamer bound for Washington, D.C. Hill, who was treated at Armory Square Hospital in the capital, eventually recovered.

Wednesday, June 1

An alarm last night. I had charge of the Picket line on the left. This morning the 16 ordered to advance. carried the enemies rifle Pitts and advanced to the brow of the Hill, when I was shot in the right thigh. alas poor Yorick-

Thursday, June 2

Suffered terribly from my operation yesterday the ball having passed through the flesh of the hip going also entirely through the Ilium bone from this point the surgeon has been unable to trace it, but I know what he thinks. He thinks that it has passed into the bowels and that I will die.

Friday, June 3

We moved yesterday in ambulances the enemy occupying the ground one hour after we left Jack Wood stuk (sic) his head in the ambulance last night and inquired for me. I was almost dead. He immediately commenced rousing me. This morning Lieut Long of Gen Bartletts staff brought in. Racked(?) up in Army wagons for White House this P.M.

Saturday, June 4

Moved last night from Hospital in Army Wagons for White House under rugged roads. night, the drivers drunk we came near dying The Train, bivouwacked 3 miles from W. Moved in the morning after Lieut. Long & self gone the Surgeon, in his knowledge of duty, had been stopped by 2 Corps train carried to Hospital borne on stretcher to Steamer Wenonah

Sunday, June 5

Passed a wretched night. Started at daylight down the river suffered excruciating pain all day. No Drs on board who appear to take interest in me, nothing to eat only what Jack forages. Passed Yorktown today, but not strength enough to look out of the window at it.

Monday, June 6

Easier this morning but filled with Hope because we are at new home. Arrived at W.[ashington] 6th St. Wharf at 10 ordered back to Alexandria. Urged to go to W. placed in Tug arrived at W. at 3 lay in the wharf til 7 then carried in Trade wagon to Armory Square Hospital.

Cold Harbor: Featured Resources

All battles of the Grant's Overland Campaign

Related Battles

108,000

62,000

12,737

4,595