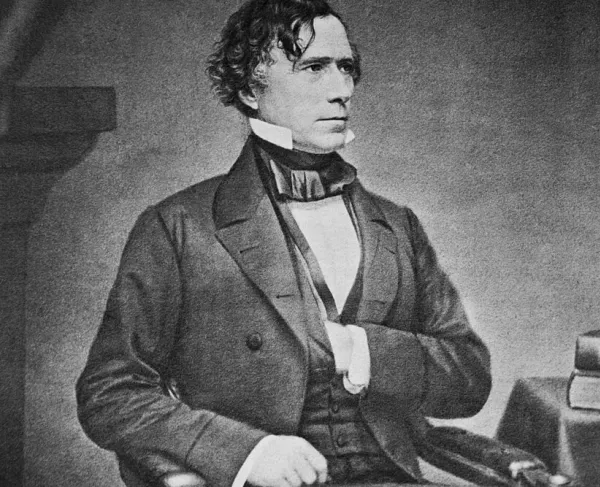

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce was born November 23, 1804, in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, to Benjamin and Anna Kendrick Pierce, the fifth of eight children. His father, Benjamin Pierce, was a significant figure in New Hampshire, having served as governor twice, an American Revolutionary War veteran, a farmer, a tavernkeeper, and a militia leader. His father's diverse roles and civic influence significantly shaped Franklin's political career.

Franklin attended a local elementary school and then academies at nearby Hancock and Francestown. In 1824, he graduated from Bowdoin College. Returning to Hillsboro in 1827 and admitted to the bar, Pierce began his law practice. Two years later, at age 24, he was elected to the lower house of the State legislature and rose to the position of Speaker. He then served in the U.S. House of Representatives (1833-37) and the Senate (1837-42), where he was the youngest member when elected. In Congress, he developed a reputation as a firm Democrat.

In 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton of Amherst, New Hampshire, the daughter of a prominent Whig and Congregational minister. They had three sons, but none survived to adulthood. Jane Pierce suffered throughout their marriage from illness and depression. Their eleven-year-old son, Benjamin, was tragically killed in a train accident just two months before Pierce became President of the United States. Jane never recovered from the tragedy and rarely participated in White House events.

When the Whig Party gained control of Congress in 1841, Pierce became dissatisfied with his position in the Senate minority. On February 28, 1842, Pierce resigned from the Senate, returned to New Hampshire and devoted more time to his law practice. He later served as Federal District Attorney for New Hampshire (1845-46). He actively participated in state political affairs and opposed the abolition movement because he felt it created national divisiveness. His policy towards slavery was not just a matter of political expediency, but a reflection of his strong belief in property rights over morality.

At the outbreak of the Mexican-American War (1846-48), Congress authorized the creation of ten regiments, and Pierce was appointed commander and colonel of the U.S. 9th Infantry. On March 3, 1847, President Polk promoted Pierce to the rank of brigadier general and placed him in command of a brigade of 2,500 recruits. At the Battle of Churubusco, Pierce sustained an injury when his horse fell on top of his leg, and he lost consciousness. It was thought that he fainted in the face of enemy fire which tarnished his reputation. Additionally, a severe case of diarrhea prevented him from participating in the storming of Chapultepec on September 13. Pierce remained in Mexico during the occupation of Mexico City.

Back in Concord, Pierce rejected the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1848 to continue his legal and political pursuits. The lands ceded by Mexico opened the slavery debate once again, dividing the United States politically. The nation nearly dissolved as Southern states threatened to secede if Congress prohibited slavery in the new territory. While Pierce usually sided with Southern states on the issue of slavery, he labored on behalf of the Compromise of 1850, which temporarily averted disaster.

As the presidential election of 1852 approached, the Whigs rejected incumbent Millard Fillmore in favor of Pierce’s former military commander, Winfield Scott. The Democratic National Convention convened in Baltimore June 1-4. Like the Whigs, the party was divided along sectional lines. Senator Stephen A. Douglas took the lead after neither Senator Lewis Cass nor former Secretary of State James Buchanan could gain the most votes. Unable to win the majority lead, Franklin Pierce was nominated as a compromise candidate, a northern Democrat who was sympathetic to the South supporting the constitutionality of slavery. On the forty-ninth ballot, Pierce won the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. The Whig Party put forth Winfield Scott, Pierce’s former military commander and Mexican American War hero. Pierce won by a landslide, taking the majority of the popular vote. Scott carried only four states to 27 for Pierce. Pierce received 254 votes in the Electoral College compared to Scott’s 42.

Pierce appointed a diverse cabinet and tried to distribute patronage among the diverse sections of his party, but he relied heavily on pro-southern advice. His expansionism in foreign affairs further incensed northerners, who resented his attempts to extend slavery using territorial acquisition. They were particularly troubled when he persuaded the British to reduce their involvement in Central America and recognize the proslavery government set up in Nicaragua. Pierce sought to acquire Hawaii, Santo Domingo and Alaska. He led a failed effort to acquire Cuba from Spain for 120 million dollars. This action provoked the contempt of Northerners, who believed it was an attempt to add slave-holding territory to support Southern interests.

Pierce’s most significant challenge to his administration was the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. Drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, it admitted the territories of Kansas and Nebraska under the terms of popular sovereignty—the citizens of each territory, rather than Congress, would determine whether slavery would be allowed. Instead of resolving the issue, this act sparked a rush of pro- and anti-slavery settlers into Kansas, leading to a series of violent conflicts. The resulting division caused the downfall of the Whig Party and the birth of the Republican Party, significantly altering the political landscape. The midterm congressional elections of 1854 and 1855 devastated the Democratic Party, underscoring the Act's profound impact.

Pierce fully expected to be re-nominated by the Democrats in the 1856 election. However, the Democratic convention scorned Pierce and Douglas and nominated the less controversial James Buchanan. Pierce endorsed Buchanan, though the two remained aloof. Hoping to improve Buchanan’s chances in the general election, Pierce installed a territorial governor in Kansas, John W. Geary, who drew the ire of pro-slavery legislators. Buchanon narrowly won the Presidential election because of a split in the Republican slate of candidates. Pierce did not soften his anti-Republican and abolitionist rants.

After leaving the White House, the Pierces remained in Washington for two months before traveling to Portugal, Europe and the Bahamas. During his travels, Pierce often wrote about the political state of affairs back home. He insisted that abolitionists cease their rhetoric to avoid a southern secession, writing that the bloodshed of a civil war would "not be along Mason and Dixon's line merely" but "within our own borders in our own streets." Pierce returned to New Hampshire in the summer of 1859, buying property in Portsmouth.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Pierce proclaimed his loyalty to the Union but was outspoken about President Lincoln’s policies, especially the Emancipation Proclamation. Due to his unpopular views of Abraham Lincoln, he lost many of his longtime friends. His wife died of tuberculosis in 1863. Distraught and depressed, he turned to alcohol. He died of cirrhosis at Concord in 1869 at age 64 and was buried in the Old North Cemetery, alongside his wife and two of his children.