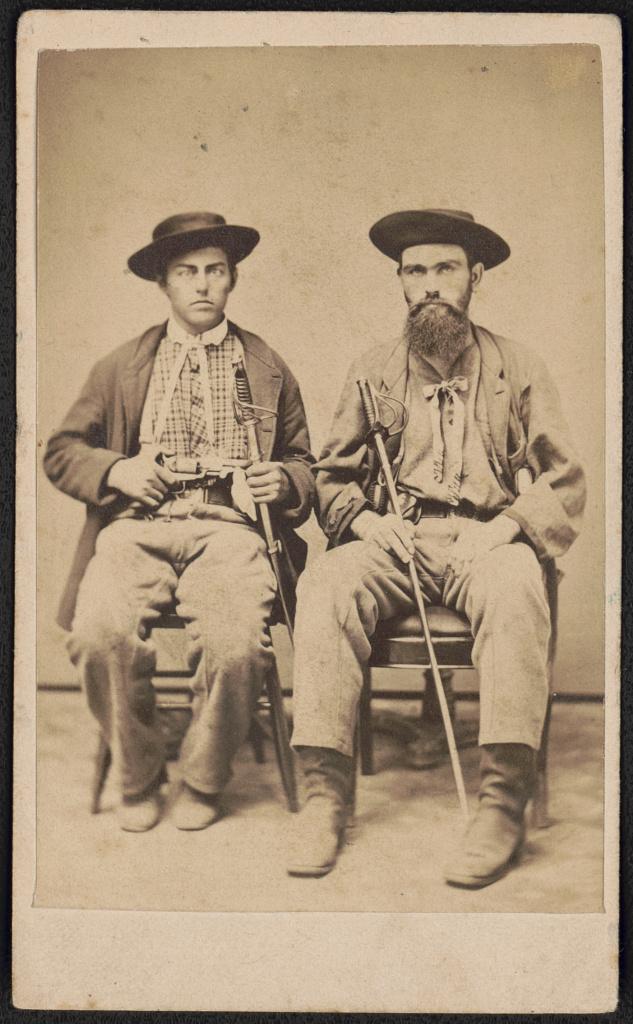

Between roughly 1855 and 1859, Kansans engaged in a violent guerrilla war between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces in an event known as Bleeding Kansas, which significantly shaped American politics and contributed to the coming of the Civil War.

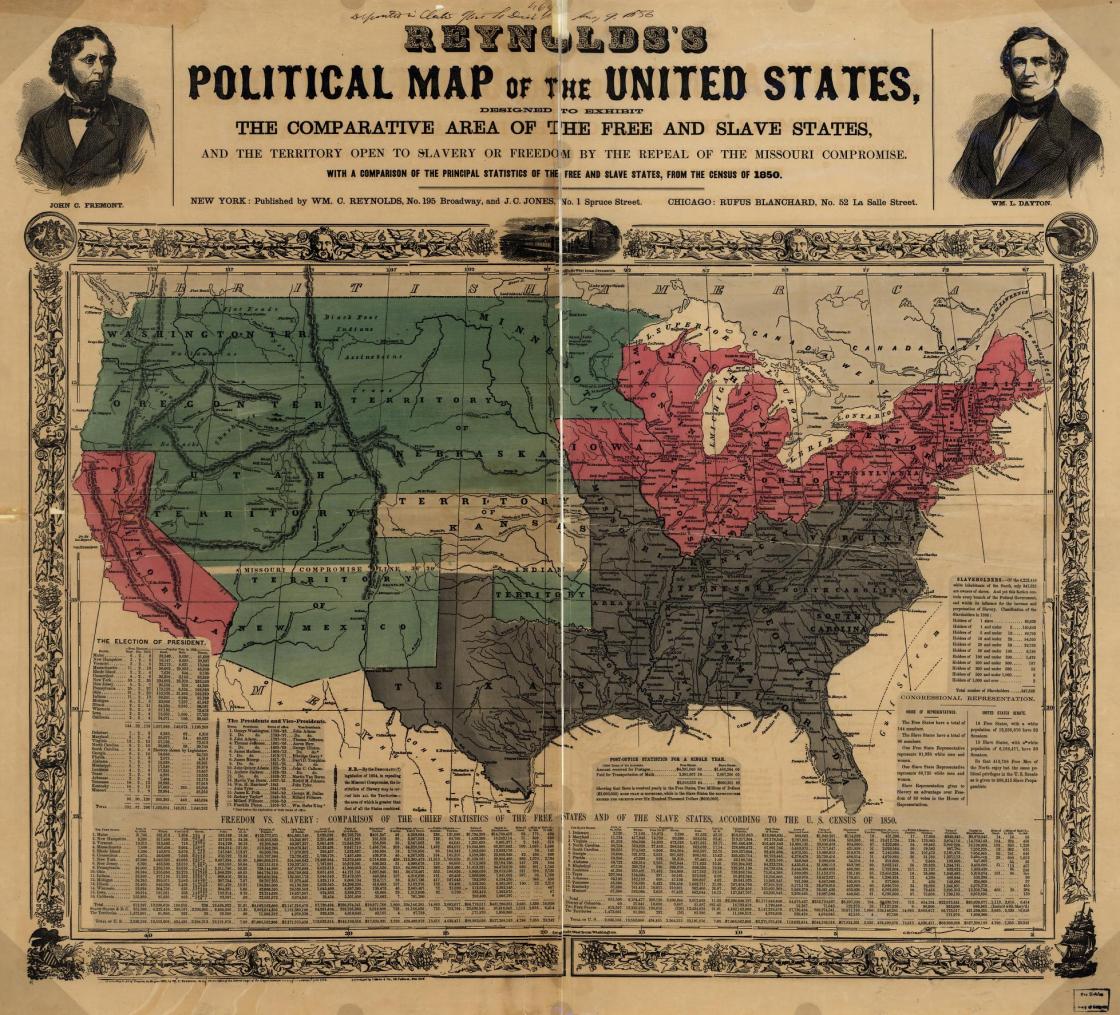

In May 1854, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act which formally organized the territory west of Missouri and Iowa (Kansas and Nebraska) and opened this space up to settlers. In a departure from previous territorial and state organization bills, Congress did not explicitly designate these territories to be either free or enslaved. Rather, the Kansas-Nebraska Act adhered to popular sovereignty a principle where the people residing in Kansas and Nebraska would determine if the territory shall be free or enslaved either by a popular referendum or through the election of pro-slavery and anti-slavery representatives to draft a constitution. Consequently, free state and slave state proponents rushed to Kansas to try to stake their claim in their efforts to either legalize or prohibit slavery there. There was not the same flurry in Nebraska as it was largely assumed that it would become a free state without much debate; however, Kansas was a different story. Located directly west of Missouri, under the Missouri Compromise, slavery would be prohibited in the Kansas territory; however, the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened up the possibility for slavery to exist in this territory and many southerners remained committed to take advantage of this opportunity and make Kansas a slave state.

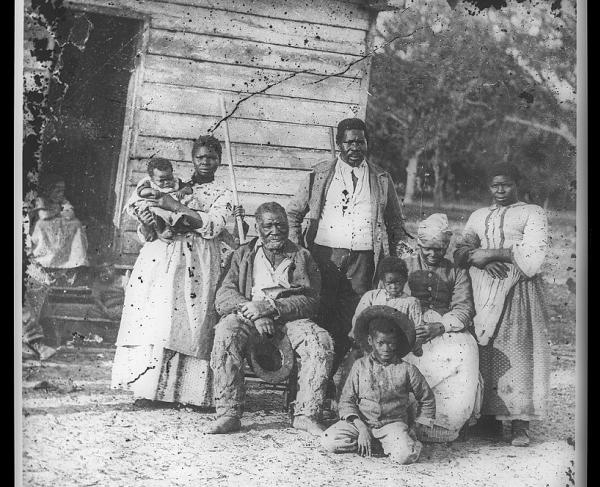

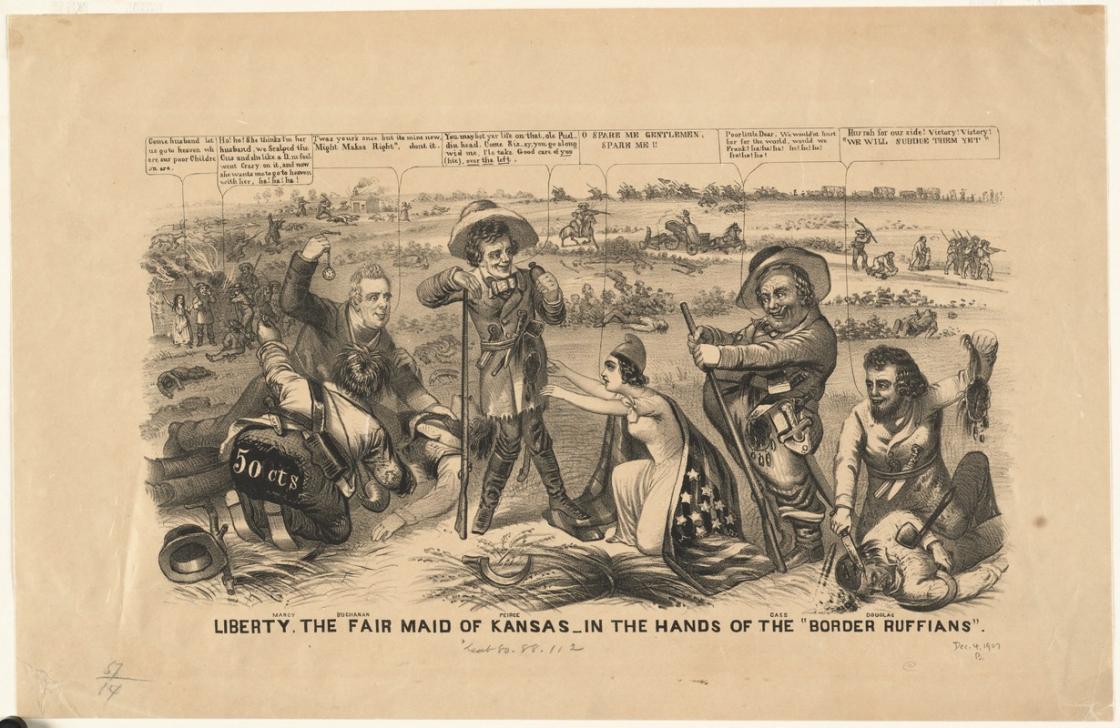

Most of the settlers who first moved to Kansas after the land went on sale were small midwestern farmers and non-slave holders from the Upper South and both groups had little interest in slavery’s extension. While there were few slave owning settlers, pro-slavery proponents were determined to legalize slavery in Kansas. On March 30, 1855 hundreds of heavily armed Missourians poured over the border, exploited a loophole as to what constituted “residency” in Kansas and voted in the first territorial election. Not only did they illegally cast their own ballots but these border ruffians also stuffed the ballot box with hundreds of fictious ballots. Consequently, a high majority of pro-slavery men were voted into the territorial legislature. This territorial legislature immediately passed draconian pro-slavery laws, including a law that stipulated the possession of abolitionist literature to be a capital offense. In response, the anti-slavery men formed their own government in Lawrence, Kansas, which the Pierce administration denounced as an illegitimate and outlaw regime. With this split between a pro-slavery government and an anti-slavery government it was only a matter of time before violent clashes broke out.

On May 21, 1856 hundreds of border ruffians once again crossed the border between Missouri and Kansas and entered Lawrence to wreak havoc—setting fire to buildings and destroying the printing press of an abolitionist newspaper. Although no one was killed, the Republican press labeled this event as the “Sack of Lawrence,” which officially ignited a guerrilla war between pro-slavery settlers aided by border ruffians and anti-slavery settlers. It is important to note that sporadic violence existed in the territory since 1855. This period of guerrilla warfare is referred to as Bleeding Kansas because of the blood shed by pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups, lasting until the violence died down in roughly 1859. Most of the violence was relatively unorganized, small scale violence, yet it led to mass feelings of terror within the territory. The most horrific incident occurred in late May 1856 when one night abolitionist fanatic John Brown and his sons forced five southerners from their homes along the Pottawatomie Creek and murdered them in cold blood. While their victims were southerners they did not own any slaves but still supported slavery’s extension into Kansas. Republicans used Bleeding Kansas as a powerful rhetorical weapon in the 1856 Election to garner support among northerners by arguing that the Democrats clearly sided with the pro-slavery forces perpetrating this violence. In reality, both sides engaged in acts of violence—neither party was innocent.

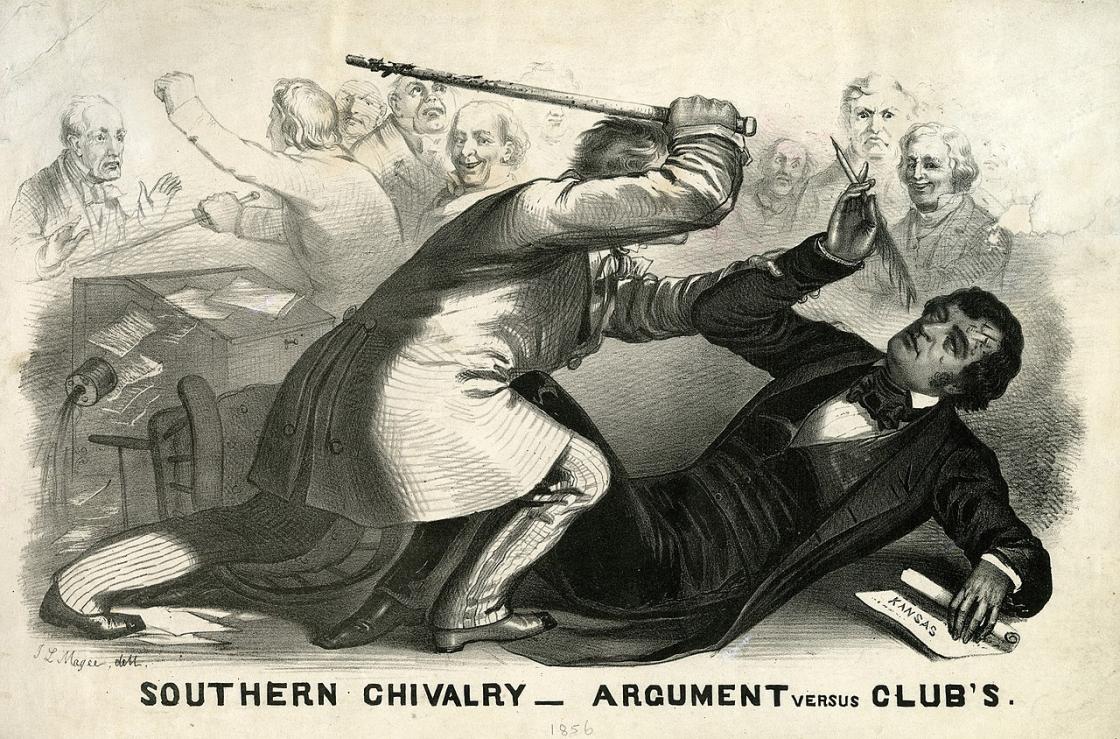

The violence surrounding Bleeding Kansas even made its way to Washington D.C. On May 19 and 20, 1856, on the Senate floor, Senator Charles Sumner (Republican-Massachusetts) gave an impassioned yet carefully rehearsed speech entitled “the Crime Against Kansas.” In this speech, Sumner denounced popular sovereignty and described Bleeding Kansas as “the rape of a virgin territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery.” Sumner accused Senators Stephen Douglas (Democrat-Illinois) and Andrew Pickens Butler (Democrat-South Carolina) of this crime and claimed they were personally responsible for the horrific crimes perpetrated in Kansas as they co-authored the Kansas Nebraska Act. Sumner also made personal and insulting remarks against the two Senators. Butler was absent for Sumner’s speech; however, his cousin Representative Preston Brooks (Democrat-South Carolina) was present for these remarks. On May 22, 1856, in retaliation for the degrading remarks made against his cousin, Brooks entered the Senate chambers and accosted Sumner at his desk, beating him with a cane until Sumner was a bloody unconscious pulp. The canning of Sumner inspired intense polarizing reactions. In general, southerners were overjoyed that someone finally stood up and defended southern honor against the perceived encroaching abolitionist sentiment that increasingly threatened their societal foundation: slavery. On the opposite end of the spectrum, northerners were absolutely horrified over what they viewed as an egregious and violent expression of the slave power against northerners which would only continue unless the slave power was stopped. Adding to this fear was the fact that Brooks retook his House seat in July 1856, facing almost no negative repercussions. In contrast, Sumner was so badly injured that he could not return to his Senate seat until three years after the ordeal.

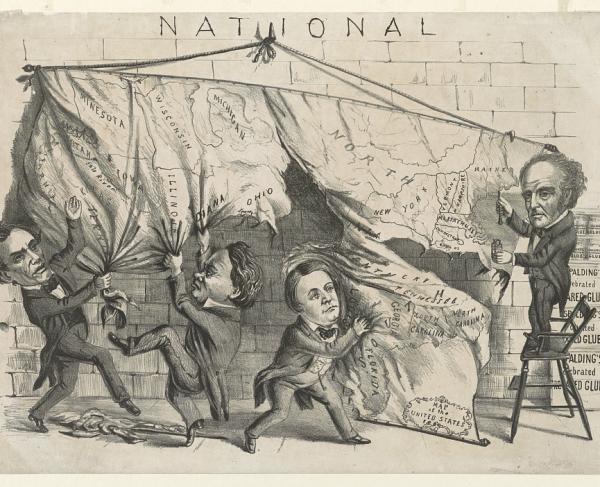

The canning of Sumner and Bleeding Kansas drove many northern Know Nothings to the Republican Party, as they viewed it as the only political party actively opposing the slave power. In order to justify their party’s existence, Republicans required evidence of the slave power’s continual harassment of northerners, which Bleeding Kansas easily provided. As the Republicans gained power the Democrats continued to fracture along sectional lines, which only increased with the crisis over the Lecompton Constitution. To southern Democrats, Bleeding Kansas illustrated the danger free soilers (who they lumped in with abolitionists) posed to the southern society, and yet, many southern Democrats felt that the northern wing of the party remained sympathetic to free soilers and were unwilling to denounce them. These increased demands to bend to the will of the southern wing of the party alienated many northern Democrats who wanted their politicians to act in the best interest of northerners, which further divided northern and and southern Democrats.

Bleeding Kansas is just one in a series of growing acts of violence surrounding slavery and abolition in the lead up to the Civil War. This event led to the crisis over the Lecompton Constitution as the violence surrounding Kansas put pressure of national politicians to accept a constitution that definitively legalized or prohibited slavery in an attempt to stop the bloodshed. Although horrified over the violence, Republicans used the events in Kansas to their political advantage to build their base, whereas the events only widened the divide between northern and southern Democrats. The political ramifications highlight the growing sectional tensions and the violence that ensured. Although not a direct cause of the Civil War, Bleeding Kansas represented a critical event in the coming of the Civil War.

Suggested Reading:

- The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Extension, and the Coming of the Civil War By: Michael F. Holt

- The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War 1848-1861 By: David M. Potter