Election of 1860 Political Cartoon, showing the four candidates dividing the electoral map.

“Believe there is the utmost danger to be apprehended from the election of LINCOLN, we shall not cease to appeal to the good and true men of all parties to cast their vote for the only candidate who have the remotest chance of obtaining the electoral vote of the entire South...” proclaimed a newspaper article printed in The Tennessean on October 24, 1860. The newspaper pointed out the division within the Democratic Party in the 1860 presidential election while noting sectionalism and fears of abolition and the Republican Party in Southern states. The United States balanced at the edge of civil war, and many voters of differing perspectives believed the outcome of the election would threaten the unity and future of the nation.

The presidential Election of 1860 set up a politically charged situation and produced deep division and new political power. The incumbent president—James Buchanan—decided not to run for re-election, opening opportunity in the Democratic Party. Eventually three candidates split the Democratic Party’s vote: John C. Breckinridge, Stephen A. Douglas and John Bell. The recently formed Republican Party had entered candidates in previous presidential elections but without success. In 1860, the Republican Party had several strong contenders during the nomination convention, but Abraham Lincoln became the chosen candidate. Slavery and the continuing questions of political power between slave and free states were top issues that all candidates and their platforms had to address or pointedly ignore.

Since 1844, James Buchanan had been a regular contender for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination. He was nominated and won the 1856 presidential election. Buchanan’s administration had faced political moments that emphasized the issue of slavery beginning to tear the country apart, setting the stage for a tense next election. Buchanan supported the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott Decision, tried to let Kansas became a slave state and held to Southern views for the cause of the economic Panic of 1857. Many people felt he lacked leadership to guide the politically fracturing nation through a difficult four years and were somewhat relieved that he had promised not to seek a second term.

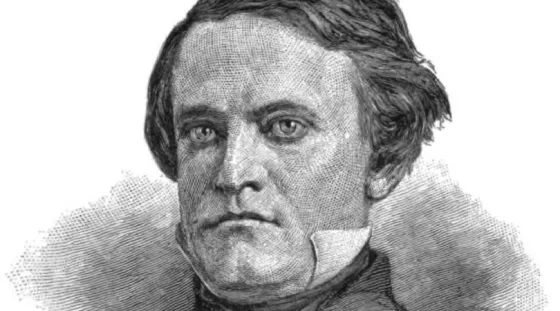

John C. Breckinridge—the youngest vice president in U.S. History—came from the Buchanan administration. Originally from Kentucky, Breckinridge had a law career and then went into politics, serving in the state legislature and later representing the Bluegrass State in the U.S. House of Representatives. When he joined the election ticket in 1856, he had supported two other Democratic Party nominees before endorsing Buchanan, and throughout the administration, the president and vice-president had a strained working relationship. However, Breckinridge showed leadership in the Senate in the presiding role. He made a notable speech in 1859 expressing hope for continued national unity but at other times seemed to regard sectional conflict as a unfortunate and inevitable reality. He also had publicly endorsed the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott Decision and spoke against John Brown’s Raid, saying it was evidence of Republicans’ preference for violence and racial equality. The Democratic Party’s Convention in Charleston, South Carolina reached no conclusion on a presidential candidate, and some of the Southern states’ convention delegates walked out. At a later convention held in Baltimore, Maryland, the protesting delegates nominated Breckinridge who agreed to run, despite his nomination fracturing the party. During the campaign season, Breckinridge’s speech-makers and managers branded him as favoring secession and sometimes presented him as a “fire-eater” willing to break up the unity of the nation. Breckinridge did not favor secession during the months of the 1860 election campaign.

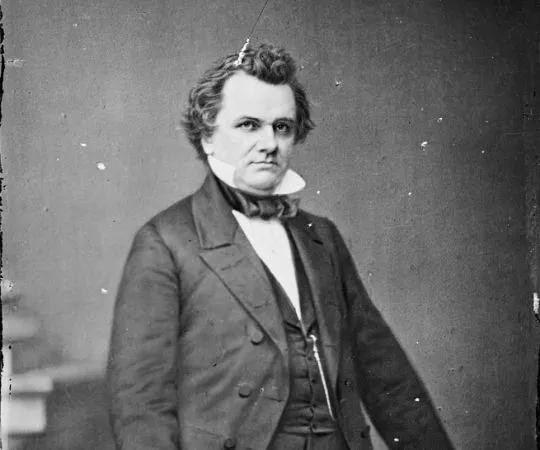

Stephen A. Douglas had been active on the political scene for decades. Hailing from Illinois for most of his political career, he served in the House of Representatives and the Senate. Achieving fame or infamy—depending on constituents’ perspective—Douglas had drafted the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. This act allowed for popular sovereignty to determine if Kansas and Nebraska Territories would be admitted to the nation as slave or free states. While the concept bypassed the Missouri Compromise and put balancing slave and free state power in Congress into the hands of the states’ residents, it also led to violence in the territories. In the 1858 Senate race, Stephen Douglas debated rising political leader Abraham Lincoln in a series of public discussions. The Lincoln-Douglas Debates put questions of slavery, abolition, free and slave state power in Congress into the newspapers and encouraged people to think about the issues. Though Douglas won the Senate race, the debates pushed the boundaries in the discussions of current affairs. At the 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, Douglas received the most delegate votes but did not get a majority since many delegates from the Southern states did not support him. During the second Democratic National Convention in Baltimore—despite the absence of many Southern delegates who bailed out and nominated Breckinridge—Douglas was nominated by the remaining majority. In the following months, he broke candidate precedent and went actively campaigning, making speeches in northern states and upper southern states. He campaigned promising to keep the Constitution as it was.

John Bell—a well-known politician in his era—had represented his home state of Tennessee in the House of Representatives and the Senate. During William Henry Harrison’s brief administration (1841), Bell served as Secretary of War. The Democratic Party’s National Convention in 1860 had reached no consensus on a candidate after meeting in Charleston, South Carolina and planned to reconvene and try again later in the year at Baltimore, Maryland. Between the conventions, the Constitutional Union Party formed a third party but drawing from Democratic Party voters. This new party nominated John Bell and highlighted a neutral position on slavery and the importance of keeping the country together. Bell struggled with popularity as a candidate, and many people thought his platform was too broad. He held hopes that none of the presidential candidates would get the necessary number of electoral votes and that, if the election was sent to the House of Representatives, he would be the selected candidate for a compromise and hopes of keeping the nation united.

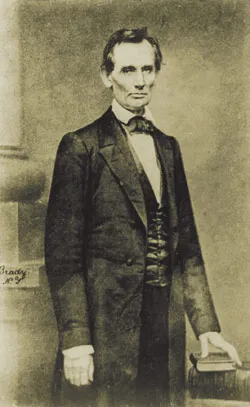

Abraham Lincoln was nominated as the presidential candidate of the Republican Party at their convention in Chicago, Illinois. Lincoln had served in the Illinois state legislature, practiced law and had a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives. Over the years, Lincoln supported free soil policies and spoke against the moral conflicts of slavery without taking hard-core stance or solution at the time. In 1858, he ran against Stephen Douglas for a Senate seat and his views became better known through the Lincoln-Douglas Debates. Lincoln lost the Senate race but continued rising in the Republican Party’s attention. In February 1860 his Cooper Union Speech made headlines for his argument that the Founding Fathers had tried to restrict slavery and that support for slavery meant moral compromise. The speech helped to secure interest in nominating Lincoln as the Republican Party’s presidential candidate, and for the first time a major political party’s presidential ticket did not have a Southern candidate or running mate. Lincoln’s supporters nicknamed him “The Rail-Splitter” and “Honest Abe” evoking his frontier beginnings and common man image. Wide Awakes—a political club that aligned with the Republican Party—marched in torchlight parades in northern communities and cities, adding extra excitement to the campaign and fueling fears in Southern states.

With multiple candidates drawing votes in the Democratic Party, the Election of 1860 became like a sectional referendum among voters; slavery and where to allow it was at the top of election issues. North, South, Midwestern and Pacific Coast States divided politically—typically rallying by the candidate whose views on slavery or what to do or ignore about slavery aligned with the regional preferences. Minnesota and Oregon were included in the election for the first time. Some Southern states did not print ballots for Lincoln.

Election Day fell on November 6 in 1860, and eligible male voters completed their trips to the ballot boxes. 81.2% of eligible voters cast their ballots—the highest voter turnout up to that point in U.S. History. When the votes were tallied, Lincoln had won the majority of electoral votes (needing at least 152 to win) but only 40% of the popular vote. The 18 states that Lincoln electorally won were all free states, and he did not win one state where slavery was legal. In the end, Lincoln carried 180 electoral votes, Breckinridge totaled 72, Bell tallied 39 and Douglas had just 12.

Tension continued to rise after the election. Stephen Douglas went on a speaking tour through Northern and Southern States, encouraging citizens to accept Lincoln’s coming presidency and appealing to them to keep the country united. Meanwhile, Southern states took steps toward secession with South Carolina declaring itself out of the union on December 20, 1860. The Secession Winter began, and six more southern states would leave and then form the Confederate States of America. Conventions and attempts to keep the country together and remain peaceful were held but had no significant effects.

When Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, his inaugural speech emphasized that he would support and defend the U.S. Constitution and asking Americans to not see themselves divided and as enemies. Just weeks later, Confederates fired on Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, and the American Civil War began.

The Election of 1860 occurred on the brink of the Civil War. The nation grappled politically with the question of slavery, resulting in divided political parties and deep sectionalism which influenced the outcome of the election. These tensions had existed and simmered for decades and in some ways the 1860 Election made Americans feel that their differences of opinions could not be reconciled. Politics highlighted. Secession tested. And Civil War would eventually decide the issue of slavery and some questions of citizenships along the principle that the nation should stay united.

Further Reading:

The Election of 1860: "a Campaign Fraught with Consequences" by Michael Fitzgibbon Holt (University Press of Kansas, 2017)

Lincoln and the Election of 1860 by Michael S. Green (Southern Illinois University Press, 2011)