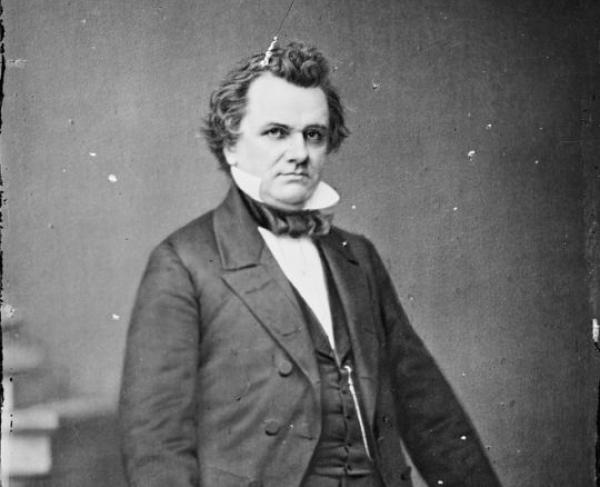

Stephen Douglas

Although a complex statesman, Stephen Douglas stood as one of the leading political figures in the coming of the American Civil War.

Stephen Douglas was born in the midst of the War of 1812, on April 23, 1813, in Brandon, Vermont and grew up on his uncle’s farm in the state. Douglas studied law in New York before leaving the northeast in 1833—settling in Jacksonville, Illinois. While in Illinois, Douglas became involved with state and local politics before he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1842. Douglas served as a Congressman for two terms until he joined the Senate in 1847—a position he held until his death in 1861. While serving in Congress, Douglas earned the nickname “the Little Giant” because at 5’4” Douglas was short in stature, heavyset, with a quick temper, yet he was a gifted orator. Douglas admired President Andrew Jackson, who greatly influenced the Little Giant’s politics. Douglas was a member of the Young Americans, a group of politically ambitious young Democrats who wanted to revitalize the party with the Jacksonian spirit of aggressive expansion and national power. This Young American platform combined with his quick fuse made Douglas unpopular among most of the establishment members of the Democratic Party.

Douglas was instrumental in the passage of the Compromise of 1850 as he broke up the compromise into individual bills and had Congress vote on those rather than the entire package, which met resistance during voting. Following this victory, Douglas sought the Democratic presidential nomination but lost to Franklin Pierce—it took forty-eight ballots at the party’s national convention before Douglas conceded. Following the deaths of the Great Triumvirate: John Calhoun (d. 1850), Henry Clay and Daniel Webster (d. 1852), the Little Giant ranked among the most celebrated and dominant national political leaders. This national recognition only grew with the passage of his most infamous piece of legislation—the Kansas Nebraska Act.

Douglas staunchly supported U.S. territorial expansion and desired a transcontinental railroad, a free land/homestead policy, and the formal organization of U.S. territories. It was these desires that led to Douglas’s most famous piece of legislation: the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was the most consequential piece of legislation passed in the antebellum era and was Douglas’s personal pet project. He worked tirelessly to ensure the passage of the legislation, which served as the foundation in his plan to settle the west. However, Douglas faced accusations of being a “Dough Face Democrat” and his creation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act had serious unforeseen consequences not only to Douglas’s political career but to the state of the Union. In the summer of 1854, following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Douglas went on a speaking tour across the North to cool passions and garner support for the bill. While on this speaking tour, he faced crowds so hostile that he recalled later he “could have traveled clear across the North by the fiery light of [his] own burning effigy.” By October the hostility began to die down and Douglas won back some support he lost. However, this speaking tour highlighted the increased anger northerners displayed against those politicians who they believed bent to the will of the slave power.

One of the more damaging effects the Kansas-Nebraska act placed on Douglas’s political career came about during the Lecompton Crisis, a direct result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Popular sovereignty served as the core of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Douglas believed that popular sovereignty was the best way to alleviate the crisis over slavery in the territories. However, when Kansas applied for statehood under the Lecompton Constitution, a constitution that violated popular sovereignty, Douglas could not support it. President James Buchanan risked his entire administration to get this constitution passed in Congress, but Douglas broke with Buchanan and the Democratic Party and joined with the Republicans to block the passage of this statehood bill in Congress. Douglas’s actions during this crisis ruined the Little Giant in the eyes of southerners because they viewed his opposition to the statehood bill as the ultimate betrayal. Douglas would never regain their support, which had significant consequences during his campaign for president in 1860.

In the 1858 Illinois senatorial race Douglas faced a challenge from future President Abraham Lincoln, a relatively unknown member of the emerging Republican Party. Although Douglas was by far the most famous politician in the West, if not in the whole country, victory in this election required some head-to-head campaigning, which Douglas achieved through a series of public debates. Between August and October 1858, Lincoln and Douglas debated seven times throughout the state on some of the most controversial topics of the time, including slavery, popular sovereignty, Douglas’s role in the slave power, Bleeding Kansas, the existence of the Republican party, race equality, etc. Newspapers published transcripts of these debates which led to Lincoln gaining recognition with national Republicans as an articulate anti-slavery leader—a significant moment in his road to the presidency. Despite Lincoln’s stellar performance in these debates, Democrats won a majority in the Illinois legislature and re-elected Douglas to the Senate. By winning another term, Douglas solidified his leadership of northern Democrats and positioned himself to be the party’s candidate in the 1860 presidential election. However, his break with the southern Democrats just a few months prior put a foil in Douglas’s plan.

By the time of the Democrat National Convention in the spring of 1860, the divide between northern and southern Democrats reached its breaking point and the schism that ensued destroyed the last remaining party with a national constituency and foreshadowed the breakup of the Union less than a year later. After fifty-seven ballots, the walkout of lower South delegates and a six-week recess, the Democratic Party still did not have a candidate to nominate for president or even a platform to run on. When the convention reconvened in Baltimore without the lower South delegates, compromise appeared to be within reach; however, that changed when the upper South delegates walked out within days of the convention. Without any sectional opposition, the convention adopted a resolution that declared they unanimously nominated Douglas for President. His running mate was Herschel V. Johnson of Georgia. The day after Douglas’s nomination, the southern delegates nominated their own candidate, the then-current Vice President John C. Breckenridge. After a decade of sectional strife, the Democratic party formally split into two separate parties—the Northern Democrats and the Southern Democrats.

This sectional split of the Democratic party contributed to Lincoln’s election. The potential four-way contest in reality became two, two-way contests: one between Lincoln and Douglas for the free states and the second between Breckenridge and Constitutional Unionist John Bell for the slave states. Unlike Lincoln, Douglas emphasized in his speeches that the United States was on the verge of a crisis with this election: Douglas told northerners that disunion was a very real possibility not simply a baseless southern threat and he reminded southerners that talks of secession were treasonous and would lead to disaster. Historians argue that in these speeches, the Little Giant showed a level of personal responsibility that was unmatched by any other candidate; after all, it was his legislation that aggravated sectional tensions and contributed to the fragility of the Union. In early October 1860, when Douglas heard that Republicans won the gubernatorial elections in Pennsylvania and Indiana, he immediately changed his campaign plans, saying “Mr. Lincoln is the next president. We must try to save the Union. I will go South.” This decision to campaign in the South where Douglas had almost no chance of winning damaged Douglas in the polls. Unlike the Republicans, Douglas recognized and actively communicated that the Union was in peril.

However, Douglas's attempts were for naught as Lincoln achieved victory in the Electoral College and received a plurality of the popular vote. Douglas came in second place for the popular vote but last in the number of Electoral College votes—receiving 29.5% of the vote but only 12 votes in the Electoral College carrying Missouri and part of New Jersey. During the secession crisis in the winter of 1860-1861, Douglas worked tirelessly alongside like-minded politicians to preserve the Union by serving on the Committee of 13 and introducing his own compromise into Congress. Despite his best efforts, the attempts for a compromise failed and the crisis divulged into war. After the firing on Fort Sumter, Douglas urged Americans to volunteer in defense of the Union and staunchly supported the war effort. However, years of drinking and exertion wore out the Little Giant and at the age of 47 he succumbed to typhoid fever on June 3, 1861.

Stephen Douglas remains an incredibly complex statesman. His decision to choose party over country with the Kansas-Nebraska Act unequivocally contributed to the coming of the Civil War. It remains to be seen if Douglas could have known that his legislation would have such devastating consequences. Yet, Douglas’s commitment to popular sovereignty and his country is admirable. By breaking with the Democrats over the Lecompton Constitution and his politically costly decision to campaign in the South, Douglas illustrated his commitment to his principles and to the Union.

Suggested Reading:

The Shattering of the Union: America in the 1850s

The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War 1848-1861

The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Extension, and the Coming of the Civil War