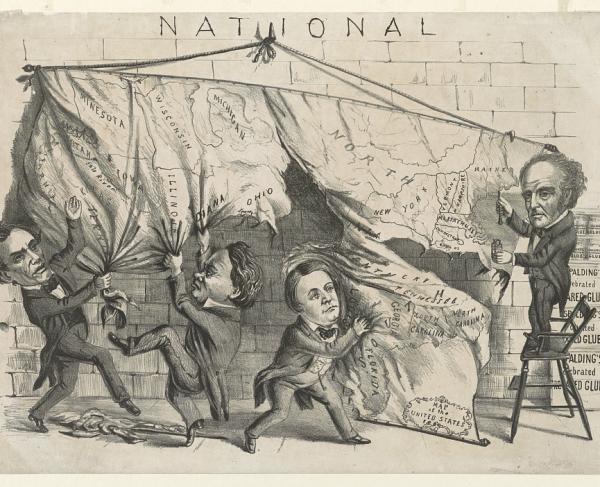

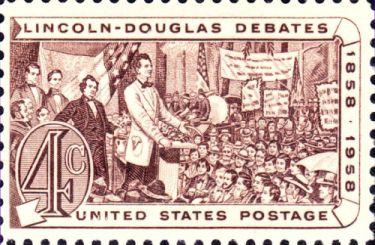

In the summer and the fall of 1858 two of the most influential statesmen of the late antebellum era, Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln faced off in a series of debates focused on slavery as they vied for a United States Senate seat representing Illinois. In the long term, the Lincoln-Douglas debates propelled Lincoln’s political career into the national spotlight, while simultaneously stifling Douglas’ career, and foreshadowing the 1860 Election.

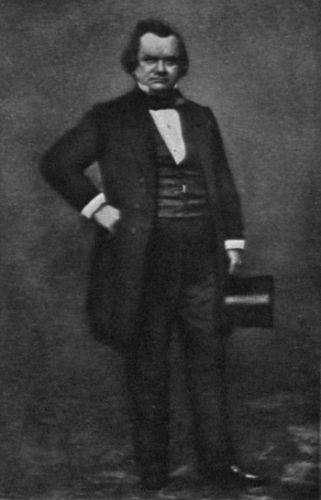

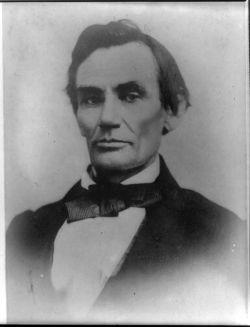

By 1858, Stephen A. Douglas was the most prominent politician in the West, if not the entire country. However, Douglas was in the midst of a massive feud with the Buchanan administration and the Democratic Party bosses over the Lecompton Constitution, which seriously affected his chances of being re-elected. The Lecompton Constitution was a state constitution for Kansas that illegitimately used popular sovereignty to push through a pro-slavery constitution that did not represent the will of Kansans. Douglas also faced an enormous backlash in the North for the Kansas-Nebraska Act, so by coming out against the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, Douglas highlighted that popular sovereignty could be used to restrict slavery in the territories, which pleased his those constituents who supported anti-slavery measures. In contrast, Lincoln was a relatively unknown, “prairie lawyer” with only one term in Congress under his belt, which he served over a decade prior to his senatorial candidacy. Lincoln was also a member of a relatively new anti-slavery party—the Republican party. Despite Douglas’ fame, and Lincoln’s lack of it, for Douglas to achieve victory in this contest required some campaigning, which led to the debates.

From August 21 to October 15, 1858, Lincoln and Douglas traveled to seven cities across Illinois to engage in public debates. Unlike our modern political debates where candidates go back and forth roughly every few minutes, the format for the debates between Honest Abe and the Little Giant featured one candidate talking for an hour followed by the other candidate speaking for an hour and a half before the first candidate was given thirty minutes for a rebuttal. Lincoln and Douglas alternated which candidate went first and which candidate responded, although, as the incumbent, Douglas spoke first in four out of the seven debates. Citizens across the Midwest traveled in droves to see Lincoln and Douglas speak, and those who missed the debates would read their transcripts in Democratic and Republican newspapers the following day. Additionally, after the election, Lincoln edited the transcriptions and published them in a book, which became popular among Republicans. It is important to note that at that time the general public did not elect senators through a popular vote as they do now. Rather, Illinoisans elected members to the state legislature and whichever party received the majority of seats would then elect their candidate to the U.S. Senate seat. Consequently, Lincoln and Douglas were not simply campaigning for themselves but also for their respective political parties.

The main focus of these debates was slavery and its influence on American politics and society—specifically the slave power, popular sovereignty, race equality, emancipation, etc. Although personally against slavery, Lincoln reiterated in these debates that he wanted to “avoid doing anything that would bring about a war between the free and slave states” and as such supported a free-soil platform rather than an emancipation platform. Lincoln believed that slaves were humans, and as humans deserve the fundamental right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” which Lincoln interpreted as only the right to not be enslaved, not the right to citizenship. Lincoln believed that one race must be superior to the others and he was “in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.” First and foremost, Douglas believed in the inferiority of African Americans and often articulated this conviction quite bluntly. However, Douglas believed just because this group was inferior did not automatically mean that they should be enslaved. To Douglas, it was up to the citizens in respective states/territories to decide if they wanted slavery—reconfirming his support of popular sovereignty. Whether blacks were free or enslaved did not matter to Douglas, what mattered was they were never to be citizens and always subordinate to whites. One of the biggest differences between Douglas’ and Lincoln’s views on slavery is that, unlike Lincoln, Douglas did not consider slavery a moral issue, an agonizing dilemma, nor was it an issue that would tear the Union apart.

In the end, Douglas triumphed over Lincoln with Democrats gaining forty-six seats to the Republican’s forty-one. However, while Douglas might have won the battle, Lincoln won the true war: the 1860 Presidential Election. The popularity of these debates and of Lincoln’s book propelled Honest Abe into the Republican spotlight, who appreciated this articulate anti-slavery leader. Lincoln’s stellar performance in these debates enabled his nomination for President in 1860.

For his part, Douglas, already on thin ice with the southern wing of the Democratic party, ruined any chance of reconciliation by supporting the Freeport Doctrine, which provided a free-soil foil to the southern pro-slavery version of popular sovereignty. During a debate in Freeport, Illinois Douglas fell right into Lincoln’s trap when answering a question about how territories could restrict slavery in the wake of the Dred Scott decision. The Freeport Doctrine is derived from Douglas’s response in which he argued that slavery could only exist in places with support from local police regulations. By unequivocally supporting this doctrine, Douglas hurt his chances to achieve victory in 1860.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates remain steeped in folklore and historians and the public alike consider them to be a representation of true grassroots democracy. The thirty years prior to these debates were marred with conflict over slavery, and never in that time did two politicians go head to head to discuss this contentious issue in such a public and articulate way. These debates reinvigorated Lincoln’s political career and propelled him to the spotlight among Republicans. Simultaneously, Douglas used these debates to reaffirm his support for popular sovereignty which further alienated the senator from the Democratic Party. All in all, these debates set the stage for a much more important showdown, both for these politicians and for the country, the Election of 1860.

Further Reading

- Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America By: Allen C. Guelzo

- The Lincoln-Douglas Debates Edited by: Edwin E. Sparks