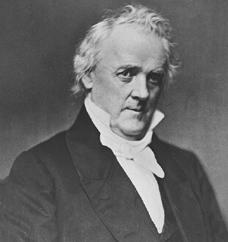

In early 1857, in response to the violence surrounding Bleeding Kansas, President James Buchanan resolved to admit Kansas as a state as soon as possible. At this time, Buchanan, a southern leaning Democrat from Pennsylvania, did not care if Kansas was a free state or a slave state—all that mattered was Kansas’s quick admission into the Union. Buchanan faced immense political pressure after the Republicans used Bleeding Kansas as political ammunition against the Democrats, arguing that the Democrats supported the pro-slavery forces who perpetrated this violence. In reality, both pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces engaged in this guerrilla war over slavery. Buchanan figured the best way to stop the violence was to definitively determine if Kansas was to be a free state or a slave state.

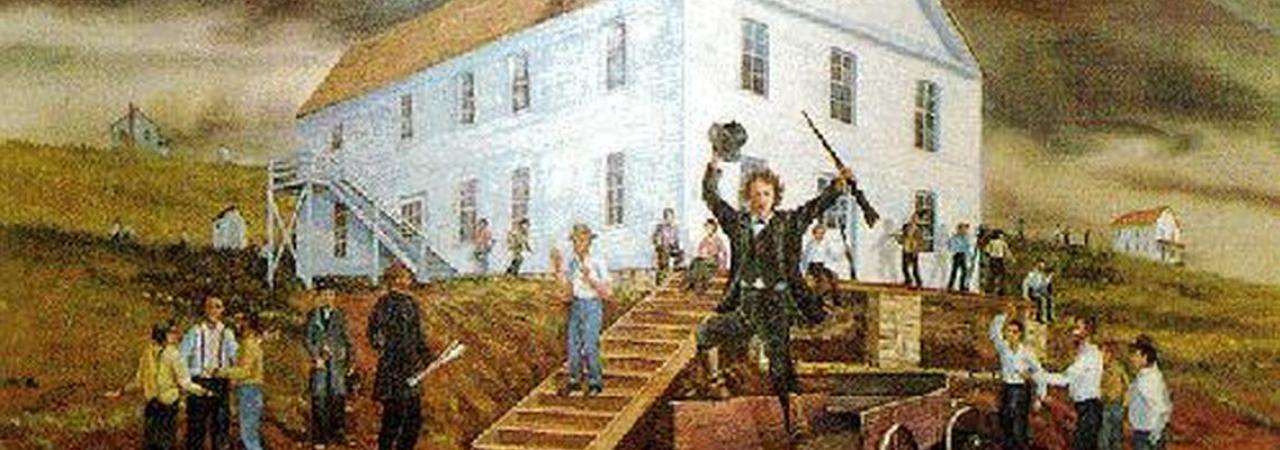

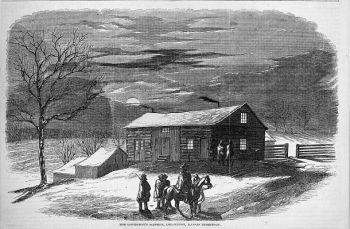

In his quest to achieve Kansas’s admission into the Union, Buchanan persuaded Senator Robert Walker (Democrat-Mississippi) to serve as the territorial governor, Walker agreed on the condition that any constitution written must be voted on entirely by all the bone fide residents of Kansas, which Buchanan approved. Prior to Walker’s arrival in Kansas, the pro-slavery territorial legislature called for a constitutional convention to be held in Lecompton, Kansas in September 1857. Free-state men refused to participate in the June 1857 election for convention delegates as they believed pro-slavery influences and fraud tainted the election. Consequently, pro-slavery delegates dominated the constitutional convention. However, the Lecompton Convention waited to act until after the territorial legislative vote in October. Initially, pro-slavery forces won that election. Similar to previous elections in the territory, widespread voter fraud permeated this election—the main culprit of this fraud were border ruffians who poured over the border from Missouri to stuff the ballot boxes. In a departure from previous elections and without the authority to do so, Governor Walker threw out the fraudulent ballots which gave anti-slavery forces control of the territorial legislature. Walker’s intervention infuriated the pro-slavery settlers and his relationship with them never recovered. Alienated from both factions and frustrated over the lack of progress, Walker left Kansas in mid November 1857, never to return.

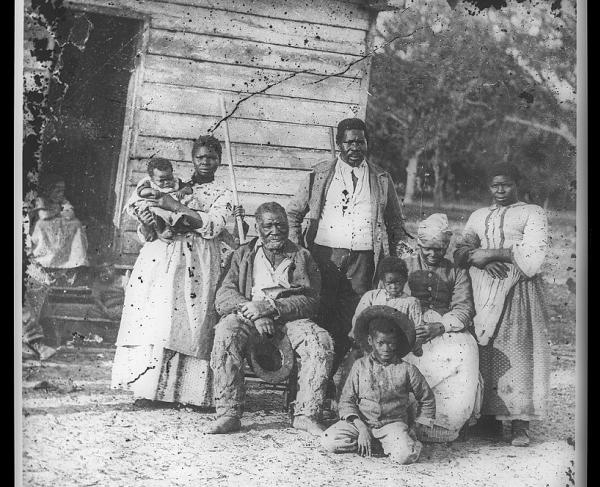

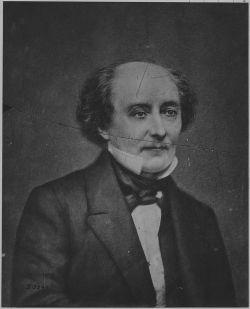

Between October 19 and November 8, 1857, the pro-slavery Lecompton Convention wrote a state constitution that deviated from the pattern of previous state constitutions. First, the Lecompton Constitution prohibited any amendment for a period of seven years. The constitution required governors to be citizens for at least 20 years and prohibited free blacks from entering the state. Additionally, the constitution guaranteed slaveholders their property rights for the approximately 200 slaves and their descendants currently residing in the territory. The constitution left the question if new slaves could be brought into the territory to the voters. The convention wanted the voters to have the option of the constitution with slavery or the constitution without slavery. There was not the option to reject the constitution entirely, which would have represented the true anti-slavery choice because even if the constitution was approved with the prohibition of new slaves brought in, it still would allow the perpetuated enslavement of those currently held in bondage and their descendants. Members of the convention argued that Kansans risked sacrificing their statehood if they voted on the Lecompton Constitution in whole. However, the vote on this document does not represent true popular sovereignty as voters were not given the option to reject the constitution entirely—the true anti-slavery option. Fresh off his resignation, Walker warned Buchannan that the Lecompton Constitution did not fulfill the promise of popular sovereignty and that blood may be shed over it. Additionally, Senator Stephen Douglass (Democrat-Illinois), the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, vehemently opposed the Lecompton Constitution because it lacked true popular sovereignty and he threatened to oppose President Buchannan publicly if he continued his support for it. Despite these objections, Buchanan’s support for the Lecompton Constitution never wavered and it became increasingly clear that he would stake his administration on the passage of Kansas statehood bill under this document.

However, despite this clear majority opposing the Lecompton Constitution, Buchanan demanded Congress approve it and admit Kansas as a slave state. His unrelenting support for the constitution alienated many Democrats, including Stephen Douglas, who felt this constitution violated popular sovereignty. Douglas broke with Buchanan and joined with the Republicans trying to block the Kansas statehood bill. Douglas represents a growing trend among northern Democrats in the late 1850s. It was becoming increasingly difficult to sell slavery to their northern constituents. To these northern citizens Buchanan’s insistence that Kansas be admitted under the Lecompton Constitution when a clear majority of Kansas did not approve of it was a clear indication of the slave power manipulating northern Democrat politicians. Additionally, northern politicians, Democrat and Republican alike, knew that if Kansas became a slave state under the objections from its citizens Republicans would dominate the midterms in 1858 and possibly even the election of 1860.

Despite Douglas’s objections the Kansas statehood bill passed the Senate on March 23, 1858 by a vote of 33 to 25. However, the main battle for Kansas statehood would take place on the other side of the Capitol. Northern anti-Lecompton Democrats and Republicans successfully blocked the passage of the bill by a vote of 120-112 in the House causing a stalemate. On March 29, 1858, they anti-Lecompton Democrats offered Buchanan a compromise to break the stalemate—they would vote in favor of the statehood bill on the condition that Kansans could amend their constitution at any time and not wait the seven years stipulated. For some unknown reason that baffles historians and commentators alike, Buchanan rejected this deal. A joint House-Senate Committee broke the stalemate when they adopted the English Bill proposed by Representative William English (Democrat-Indiana) which proposed the Lecompton Constitution be sent back to Kansas to be voted on again. On August 2, 1858, Kansans overwhelmingly rejected the Lecompton Constitution 11,300 to 1,788 and Kansas remained a territory until 1861 when it was admitted as a free state.

Building on the consequences of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Bleeding Kansas, the crisis over the Lecompton Constitution further fractured the Democratic Party while building the Republican’s base. However, Stephan Douglas’s break with the party had significant and damaging consequences. Southerners felt betrayed by Douglas’s actions and blacklisted him. This was one of the reasons that the Democrats ran two sectional candidates in the Election of 1860, Stephen Douglas as the Northern Democrat candidate and John C. Breckenridge as the Southern Democrat candidate. It was this split in votes which made the Democratic Party unable to stop Lincoln’s Election, which served as the main catalyst for the secession of the lower South states. While the crisis over the Lecompton Constitution did not directly cause the Civil War, the political fallout that ensured was critical to the war’s coming.

Suggested Reading:

- The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery and the Coming of the Civil War

- The Shattering of the Union: America in the 1850s