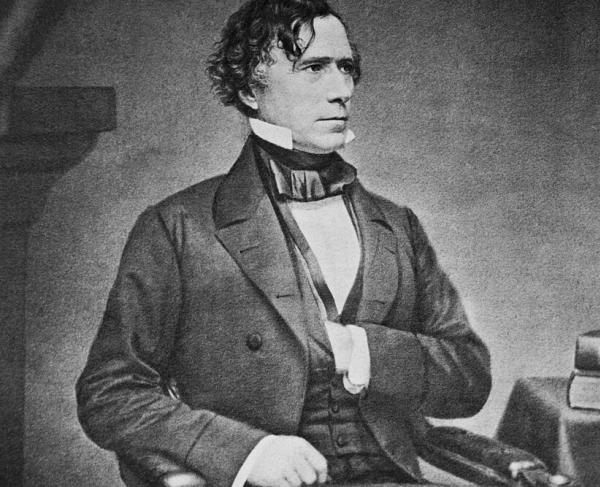

James Buchanan

Historians often label James Buchanan as one of the worst presidents in United States history. His presidency was marked with conflict, a conflict that had been brewing for over thirty years. Yet, Buchanan’s actions, and at times his inactions, aggravated sectional tensions to the point where the Union dissolved.

James “Old Buck” Buchanan was born to wealthy Irish immigrants on April 23, 1791, in rural Cove Gap, Pennsylvania. He entered Dickinson College at the age of 16, two years later he graduated with honors. After his graduation in 1809, Buchanan studied law and as his legal career grew so did his political one. Buchanan served in a reserve unit during the War of 1812 and did not experience any combat, and shortly after the war, the Old Buck served in the Pennsylvania State Legislature before his election to serve in the United States House of Representatives from 1821 until 1831, where he sat on the House Judiciary Committee.

Initially a Federalist, Buchanan left that party as it began to crumble and attached himself to the political movement of the rising star in the Democratic-Republican Party: Andrew Jackson. When the Democratic-Republican Party morphed into the Democratic Party under Jacksonian values in 1825, Buchanan became a leader of the party in Pennsylvania. Although Jackson turned on Buchanan when he believed the young Congressmen participated in the “corrupt bargain” that cost Old Hickory the election Buchanan remained loyal to Jackson and helped him win the state of Pennsylvania in the 1828 and 1832 elections. Jackson rewarded Buchanan’s loyalty by appointing him as Minister to Russia in 1832. When Buchanan returned from Russia in 1833, he ran for the Senate and won. While in the Senate, the Pennsylvanian served on and eventually chaired, the Foreign Relations Committee. From 1845 until 1849, Buchanan served as Secretary of State under President James Polk and worked toward a compromise between Polk and England over Oregon’s northern boundary. Following President Zachary Taylor’s election in 1848, Buchanan returned home to Pennsylvania with presidential ambition in his eyes.

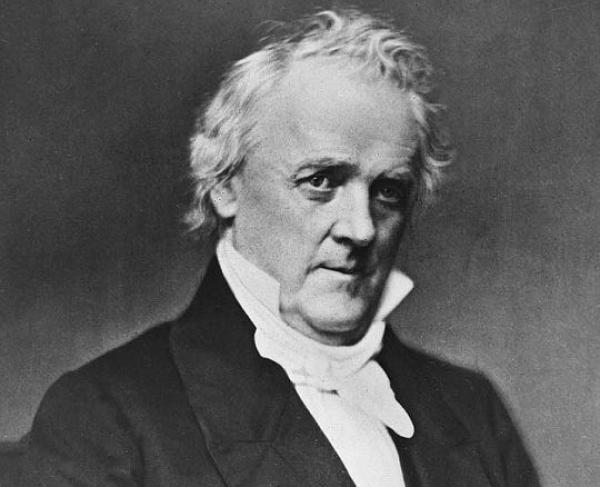

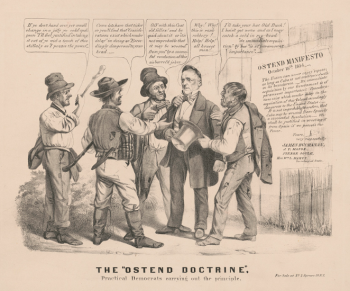

The Old Buck and Senator Stephen Douglas, also known as Little Giant, bitterly fought for the Democratic nomination in 1852 until the little known New Hampshire politician Franklin Pierce came on the scene and secured the nomination. After this showdown, Buchanan despised Douglas, as he perceived Douglas’s candidacy denied Buchanan the presidency—their relationship never recovered. President Piece appointed Buchanan to the position of Minister to England which turned out to be a blessing for Buchanan’s presidential ambitions as it kept him active in politics, but distant from the turmoil in the Pierce administration, specifically the fallout from the Kansas-Nebraska Act. When Buchanan’s plan to purchase or conquer Cuba in order to expand plantation land and slavery came to light in 1854 with the Ostend Manifesto, he enraged anti-slavery forces but garnered support among southerners who viewed the Pennsylvanian as a politician who sought to expand and protect slavery. This support proved to be vital to his presidential campaign.

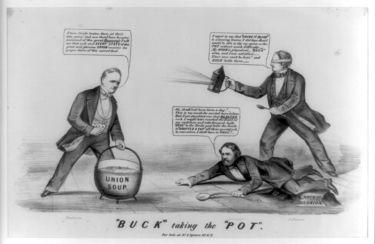

Buchanan’s absence during the Kansas-Nebraska Act debacle enabled his nomination for President in 1856. Party leaders viewed Buchanan as a compromise between the splintering northern and southern wings of the party—as Buchanan was a northern man with southern principles. Running against Buchanan was the politically incompetent John C. Frémont, nominated by the burgeoning Republican Party, and former President Millard Filmore of the practically dead Know Nothing Party. In this three-way electoral contest, Buchanan was the only true national candidate as both Frémont and Filmore catered to sectional interests. Southerners threatened to secede if Frémont was elected, which foreshadowed their reaction to Abraham Lincoln’s candidacy only four years later. This threat of secession aided Buchanan as northerners were more inclined to vote for a candidate that would prevent disunion. Although Buchanan won the election, he lost to Frémont in the North, carrying only five states. In contrast, Buchanan won every southern state except Maryland. In doing so, the Pennsylvanian was the first president since Andrew Jackson in 1828 to win the presidency without carrying a majority of free states along with the slave states. This marked the ever-growing sectional imbalance in the Democratic Party.

Buchanan’s presidency was marred with conflict; however, one of the most significant events of his presidency began to unfold even before his inauguration. At the heart of the Dred Scott v. Stanford case was the status of slavery in the territories, an issue that had plagued American politics since the Missouri Compromise. Buchanan desperately hoped that the Supreme Court would unequivocally settle this massive issue before his inauguration in March of 1857. In violation of presidential ethics, on February 3, 1857, the president-elect began corresponding with Justice John Catron of Tennessee. Buchanan inquired as to when the country would learn about a decision and if the decision would be narrowly focused or broad. In his response, Catron did not answer as to when a decision would be handed down but did mention that the territorial question would be involved. On February 23, 1857, Justice Robert Grier of Pennsylvania responded to an earlier letter of Buchanan and tipped him off to the coming decision, writing “six if not seven will declare that the compromise law of 1820 to be non-effect.” With this prior knowledge in his inaugural address, Buchanan referred to Dred Scott as a decision that would “speedily and finally” resolve all questions about slavery in the territories, and he would “cheerfully submit to that decision.”

On March 6, 1857, two days after Buchanan’s inauguration, Chief Justice Roger Taney released the Court’s decision. In this decision, the Court ruled that black Americans, free and enslaved, lacked citizenship rights and thus lacked the ability to sue for their freedom. Most significantly, the Court ruled that neither Congress nor a territorial government could restrict slavery in the territories, as doing so violated the fifth amendment. Although Buchanan certainly overstepped by corresponding with these justices and encouraging them to release a broad decision instead of a narrow one, his critics imagined something much worse. In their minds, the “slave power” controlled every aspect of this case—from the president and justices to Dred Scott’s lawyers—all were members of the slave power and conspired to deliver a radical pro-slavery decision. It was not the fringe members of society who propagated this fanatic conspiracy. William Seward of New York, the most famous Republican politician at the time accused Buchanan and the Supreme Court of “conspiracy, tyranny, deception, and subversion.” Lincoln also propagated this theory although he toned down his rhetoric, often using humor to reproach Buchanan. There is no explicit evidence that the Dred Scott decision was a large plot orchestrated by the slave power. The very fact that Buchanan inappropriately corresponded with the justices highlights his lack of knowledge prior to Justice Grier heavily alluding to the decision. In reality, it was a last minute decision to deliver such a broad verdict. However, Buchanan continued to face charges of being a “Dough Faced” Democrat and the controversy surrounding the decision and his role in it plagued his administration.

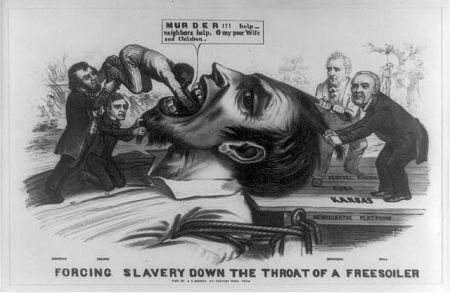

However, Buchanan’s role in the Lecompton Crisis proved to be detrimental to his presidency. As soon as Buchanan took office, he resolved to rapidly admit Kansas into the Union, either as a slave state or a free state. As time went on, it became increasingly clear that Buchanan would not settle for anything except Kansas’s admission under the Lecompton Constitution, a pro-slavery constitution that violated popular sovereignty. The Old Buck had strong personal and professional relationships with many of his southern colleagues, relationships that would be destroyed if he came out against the Lecompton Constitution. Additionally, Buchanan faced political ruin if he denounced the constitution as a violation of popular sovereignty as southerners were his main political base: 112 out of 174 of his electoral college votes came from the South.

Consequently, Buchanan firmly supported the Lecompton Constitution and staked his reputation on its passage through Congress. Putting a foil in Buchanan’s plan was his old rival Senator Douglas who publicly opposed this bill and worked with Republicans to stop its passage. With memories of his failed bid for the 1852 nomination still on Buchanan’s mind, he was always frosty to the senator because the experienced statesmen often felt threatened by the younger Douglas who was a gifted orator and by all accounts a better politician. Douglas’s opposition turned out to be fatal as he mobilized enough northern Democrats in the House to block the passage of the bill. These northern Democrats offered to end the stalemate and vote for the constitution, slave clause and all, if Kansans could amend their constitution at any time and not wait the seven years currently stipulated. In one of the most puzzling and self-destructive decisions of his presidency, Buchanan rejected this offer. Eventually, the Lecompton Constitution failed for good, and it remained a territory until 1861.

Buchanan’s unwavering support for the Lecompton Constitution stressed the already fractured relationship between the northern and southern wings of the party. Unlike with the Kansas-Nebraska Act when Piece took similar enormous risks for it to pass, Buchanan’s political risks never paid off. In the 1858 midterms, northern Democrats faced a bitter fight with almost 50% of northern Democratic seats being turned over to Republican ones, and Republican’s gained control of the House of Representatives. Of the northern Congressmen that kept their seats the majority opposed the Lecompton Constitution. Buchanan’s actions during this crisis made it increasingly clear that the Democratic Party, as a national party, would cease to exist if the President continued to subjugate northern interests to southern ones. Additionally, Douglas’s reelection combined with the failure of the Lecompton bill illustrates that Buchanan had almost no control over his party and lacked true political power. By the end of 1858, Douglas was the most powerful man in the Democratic party.

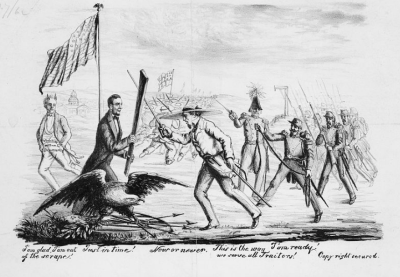

In mid-October 1859 abolitionist fanatic and murderer John Brown raided the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia in an attempt to initiate a slave rebellion that would lead to the abolition of all slaves. Sectional tensions exploded after this event with northerners viewing Brown as a martyr and southerners terrified that their greatest fear came true: servile insurrection led by secret abolitionists masquerading in southern society. In another huge misstep in his presidency, Buchanan did nothing to alleviate these sectional tensions, thereby allowing them to fester. While his inaction with John Brown’s “raid,” aggravated sectional tensions, his inaction during the secession winter proved to be fatal—both to his reputation and more importantly to the Union.

Buchanan did not seek the Presidential nomination in 1860 as he vowed before his inauguration to only serve one term. Abraham Lincoln’s victory triggered the secession of the lower South states with South Carolina issuing their ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860. During this period, Buchanan tried to remain conciliatory, neither wanting to alienate Unionists nor secessionists but in doing so pleased no one. Buchanan refused to take any action against the South which enabled the creation and operation of the Confederate government, which possibly could have been prevented with decisive action. Buchanan’s inaction simply prolonged the aversion of the war. His official response to the crisis came in his annual message to Congress on December 6, 1860, Buchanan recommended a new Constitutional Convention to solve the crisis which never came into fruition. Buchanan’s anti-climactic annual message reinforced the perception that the Buchanan White House was weak, and that the President simply wanted to avoid war until he left office.

After Lincoln’s inauguration, Buchanan retired to Pennsylvania to live a relatively quiet life. In response to vicious attacks on his presidency, Buchanan wrote his memoirs in which he attempted to defend his name. These memoirs were published in 1866, a year after the Civil War ended. After the publication, Buchanan became a recluse, rarely leaving his home which he died in on June 1, 1868, of respiratory failure.

Before the Civil War was even over contemporaries blamed Buchanan for the war, a pattern that continues to this day. And while the Old Buck certainly is responsible for the events that unfolded, during his presidency, he is not the only character responsible for the events. This crisis had been brewing for over thirty years and grew each time a politician chose their party or a specific policy over Union. Most historians agree that in the 1850s the war could have been averted but politicians, Buchanan included, made disastrous decisions which only aggravated the crisis and pushed the country closer and closer to war.