The Fall of Fort Henry

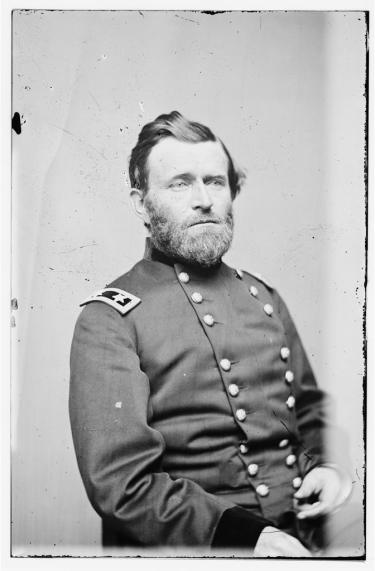

Beginning in the autumn of 1861, a variety of voices in the Union command structure began speculating on the possibility of seizing Forts Henry and Donelson to open a water route into the Confederate heartland. On January 30, 1862, Brig. Gen. Ulysses Grant received the long-anticipated word that he and Flag Officer Andrew Foote would lead a joint expedition against the twin forts. The two divisions of infantry under Grant numbered some 15,000 men and were accompanied by Foote’s flotilla of ironclad and timberclad gunboats.

Spirits in the Union ranks were high, but the situation inside Fort Henry was vastly different. The 2,800 Confederates under Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman were poorly armed — many of them with flintlock rifles dating from the War of 1812 — and the inclement weather had left many ill. Although Fort Henry’s walls were 20-feet high and 20-feet thick at the base, winter rains had swollen the river, leaving the parade ground submerged beneath two feet of water and much of the powder in the magazines damp.

On February 4–5, Grant’s infantry disembarked, out of range of Fort Henry’s guns. Upon learning of the size and composition of the Union force from scouts, Tilghman withdrew entirely from the incomplete walls of Fort Heiman, on the west bank of the river, and dispatched the majority of the force inside Fort Henry overland to the more defensible Fort Donelson. Still, he determined to make a stand against the coming gunboats rather than abandon Fort Henry to the enemy.

At noon on February 6, 1862, Foote began his assault, entering the fray with four ironclads and three timberclads. As ordered, the ships closed to a point-blank range of less than 300 yards, wreaking havoc on the Confederate defenses. Before long, all four of the defensive heavy guns had been lost and 21 Southerners were casualties, prompting Tilghman to ask Foote for terms. The sailor’s response presaged Grant’s 10 days later at Fort Donelson: “Your surrender will be unconditional.”

In a ceremony onboard the Cincinnati, 12 officers and 82 men surrendered. When Grant’s infantry arrived a few hours later, they found a large quantity of provisions and six mobile cannons mired in the mud, evidence of the alacrity with which the last vestiges of the Confederate force had vacated the doomed position.

In the fighting, the Confederate guns did inflict some significant damage on Foote’s fleet. A direct hit to the middle boiler knocked the ironclad Essex out of commission, causing 32 casualties in one shot and disabling her for the rest of the campaign. The Cincinnati took 32 hits, the St. Louis seven and the Carondelet six.

With the Tennessee now open before him, Foote dispatched his three timberclads, Tyler, Conestoga and Lexington, as far as Muscle Shoals, Ala., destroying supplies and infrastructure as they went, even capturing the uncompleted Confederate ironclad Eastport. The raid’s critical flaw was sparing the railroad bridge at Florence, Ala., which would play a critical role in the Battle of Shiloh two moths later.