How much do you know about the final days of the war in Virginia? Here are some facts about the battle and the surrender to help shed a little light for newcomers and test the knowledge of veterans.

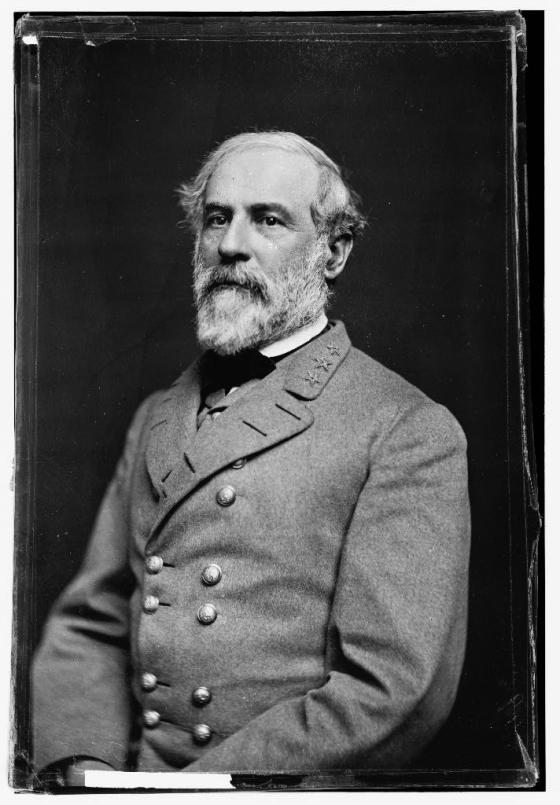

Fact #1: Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant following a battle earlier that morning.

The surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia – the most celebrated Confederate army – followed a defeat in the final battle of the war in Virginia. The Battle of Appomattox Court House was the climax of a campaign that began eleven days earlier at the Battle of Lewis’ Farm.

Fact #2: In just over one week before the battle at Appomattox Court House, Lee had lost more than half of his army.

During the Siege of Petersburg from June 1864 - April 1865 Lee had about 60,000 men under his command to oppose more than 100,000 Union troops. On April 1, a Union victory at the Battle of Five Forks made it possible for Grant's forces to wrap around Petersburg, leaving Lee’s entrenchments vulnerable. When Federals broke through Confederate defenses at Petersburg the next day, Lee was forced to evacuate.

Thousands of soldiers were captured at the battles of Five Forks, the Petersburg Breakthrough, and especially Sailor’s Creek – where about a quarter of the army surrendered after being cut off from Lee. Grant's forces harried the Rebels constantly as they continued to retreat west along their tenuous supply lines. Desertion was rampant among the starving and beleaguered soldiers, and Confederates took heavy casualties at several battles.

Fact #3: At Appomattox Court House, Lee made his final attempt to escape Grant's reach.

Heavily outnumbered and low on supplies, Lee’s situation was dire in April 1865. Nevertheless, Lee led a series of grueling night marches, hoping to reach supplies in Farmville and eventually join Maj. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army in North Carolina.

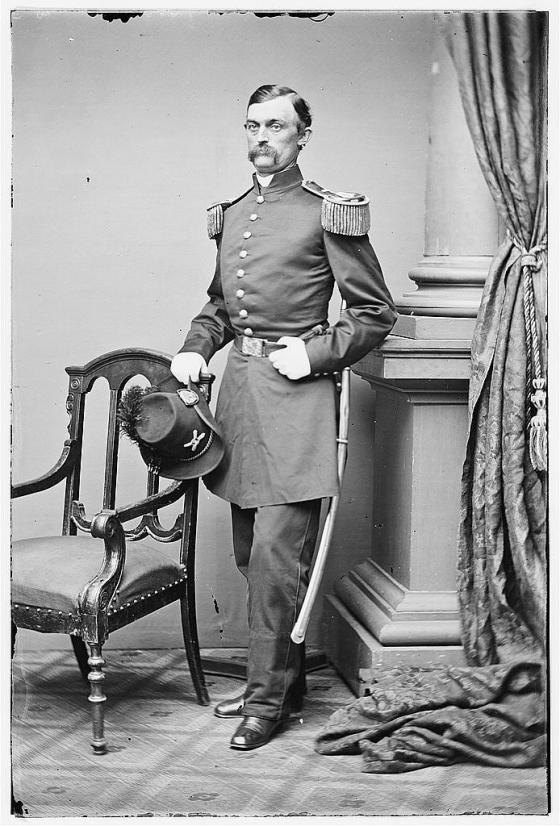

On April 8, the Confederates discovered that the army’s escape was blocked by Federal cavalry. The Confederate commanders decided to try to break through the cavalry screen, in the hope that the horsemen were unsupported by other troops. Grant anticipated Lee’s attempts to escape, however, and ordered two corps (XXIV and V) under the commands of Maj. Gen. John Gibbon and Bvt. Maj. Gen. Charles Griffin to march all night to reinforce the Union cavalry and cut off Lee’s escape.

At dawn on April 9, the remnants of Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon’s Corps and Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry drove off the Federal cavalrymen. Upon capturing the ridge that the Yankees had defended the Confederates realized that they had been gravely mistaken: Gibbon and Griffin’s corps had completed their night marches, and promptly drove back the weary Rebels.

Fact #4: Lee decided to surrender his army in part because he wanted to prevent unnecessary destruction to the South.

When it became clear to the Confederates that they were stretched too thinly to break through the Union lines, Lee observed that “there is nothing left me to do but to go and see Gen. Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.” Not all his subordinates agreed with him; one such officer, Brig. Gen. Edward Porter Alexander, suggested that Lee disperse the army and tell the men to regroup with Johnston’s army or return to their states to continue fighting. Lee rejected the idea, explaining that “if I took your advice, the men would be without rations and under no control of officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal in order to live. They would become mere bands of marauders…. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from.”

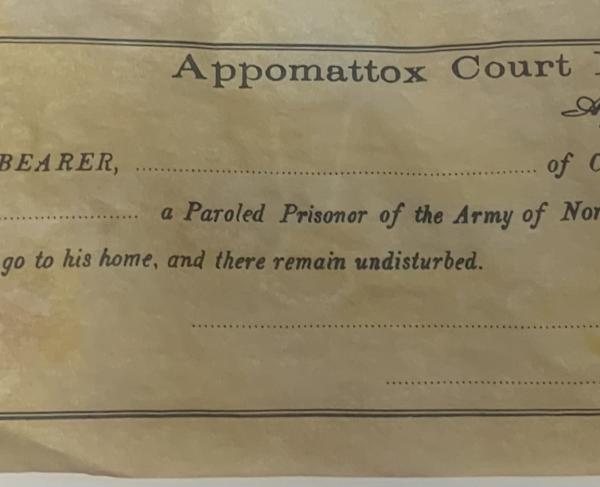

Fact #5: Grant agreed to parole the entire Army of Northern Virginia rather than take them as prisoners.

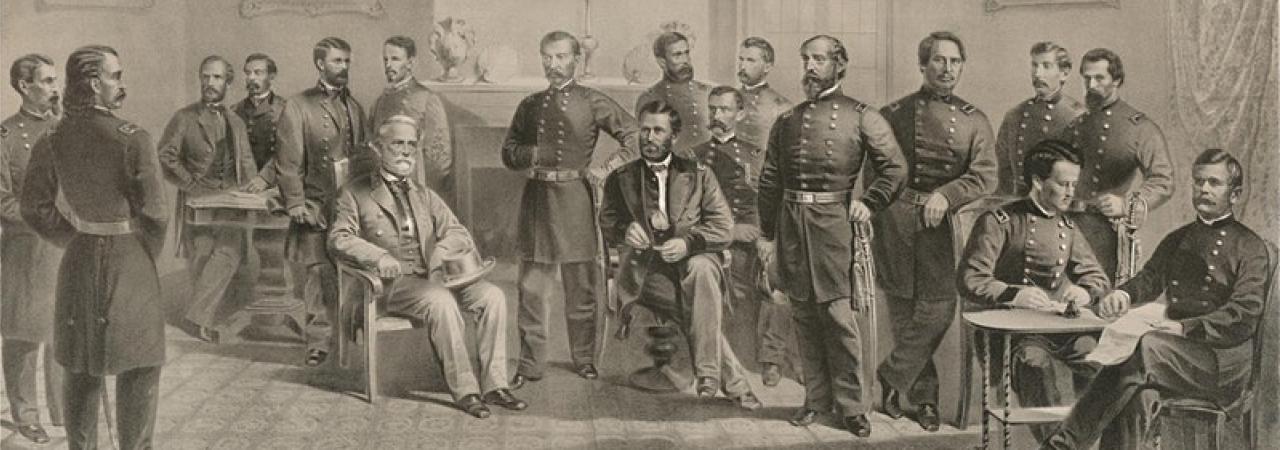

At around 1:30 in the afternoon on April 9, Lee and Grant met at the McLean House in the village with a group of officers. The Union general granted Lee favorable terms of surrender: allowing the men to return to their homes and letting the officers, cavalrymen, and artillerymen keep their swords and horses if the men agreed to lay down their arms and abide by federal law. Grant even supplied food to the Rebels, who were desperately low on rations.

Grant's leniency – together with Lee's reluctance to risk a guerrilla war – can be partially credited for the relative peacefulness of the Reconstruction.

Fact #6: The surrender terms were drafted by a Native American.

The official copies of the surrender terms signed by Lee and Grant were drafted by Grant’s personal military secretary, Lt. Col. Ely S. Parker. Parker was a Seneca Indian Chief from New York who had studied law. He became friends with Grant after the Mexican-American War, and Grant secured an officer’s commission for him. He accompanied Grant to the McLean house on April 9 and witnessed the surrender. Parker would eventually rise to the rank of brigadier general.

Fact #7: Wilmer McLean moved to Appomattox Court House to avoid the war.

In summer 1861, Wilmer McLean and his family lived in Manassas, Virginia. His house was on the outskirts of the battlefield, and was used as Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard’s headquarters. After the battle, McLean began selling sugar to the Confederate Army, and moved to Appomattox Court House where he believed he would be able to avoid the fighting and the Union occupation, which impeded his work. After the war, McLean would famously observe that "The war began in my front yard and ended in my front parlor."

Fact #8: Union troops saluted their former enemies at the surrender ceremony.

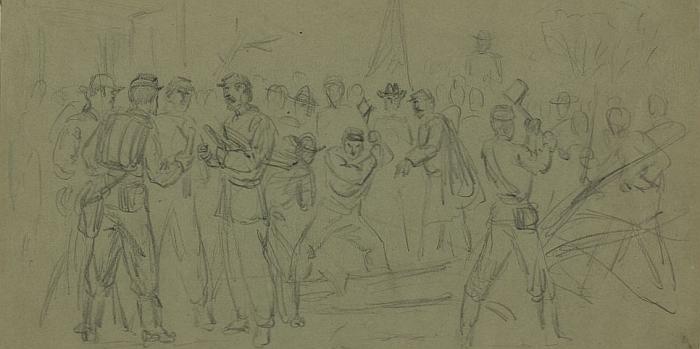

The surrender was a highly emotional affair for the participants, many of whom had been fighting for four years. Soldiers on both sides cheered and cried – often at the same time – upon hearing the news.

The formal ceremony and collection of weapons took place on April 12 under the supervision of Brig. Gen. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. As ranks of Confederate soldiers came forward to hand over their weapons and flags, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute their defeated adversaries as a gesture of respect. Other witnesses also reported that interactions between Yankees and Rebels were almost entirely kind and friendly.

Fact #9: The surrender agreement at Appomattox did not end the war.

After Lee's surrender, the Army of Tennessee remained in the field for over two weeks, until Johnston finally surrendered the army and numerous smaller garrisons to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on April 26. Johnston's surrender was the largest of the war, totaling almost 90,000 men.

The final battle of the Civil War took place at Palmito Ranch in Texas on May 11-12. The last large Confederate military force was surrendered on June 2 by Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith in Galveston, Texas, and the broken country began to pick up the pieces from years of fighting.

Fact #10: After the surrender, many already historic artifacts were taken or destroyed by soldiers seeking souvenirs.

After Lee left the McLean House on April 9, some of the Union officers present promptly bought much of the furniture in McLean’s parlor. The phenomenon was not limited to the upper echelons – soldiers of all ranks from both armies tried to take a piece of their experience home with them. Northerners bought Confederate dollars from the Rebels, and soldiers tore up their own regimental flags as souvenirs.

Since the nineteenth century, a more concerted effort has been made to preserve the history of Appomattox Court House for everyone to experience. The Appomattox Court House National Historic Park was created in 1940, and encompasses about 1,700 acres, including some of the battlefield land, the Court House, Lee’s headquarters, and a reconstructed McLean House (still missing much of its original furniture, which is scattered across the country). The American Battlefield Trust has preserved additional acreage which includes ground used during Griffin’s counterattack and land where Bvt. Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s cavalry division checked an advance down the LeGrand road by members of Brig. Gen. Martin Gary’s Confederate cavalry brigade.

Bonus facts:

- Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee was Robert E. Lee’s nephew, and participated in his uncle’s final council of war on April 8 with Generals Longstreet and Gordon.

- Robert E. Lee’s son, Maj. Gen. William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee, also participated in the battle, commanding a cavalry division in the battle under the leadership of his cousin Fitzhugh.

- Lee's family was almost certainly on his mind as he considered surrender; both his oldest son (Maj. Gen. George Washington Custis Lee) and his youngest son (Capt. Robert E. Lee, jr.) were missing in action. As it turned out, Custis was captured at Sailor's creek, and Robert had been cut off from the army and eventually surrendered after hearing news of Appomattox.

- Ever one to overestimate his importance, when a Confederate envoy asked him for a truce while the surrender was arranged, Custer instead demanded Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s unconditional surrender. Fortunately, Gen. Sheridan (Custer’s commanding officer) arranged for the ceasefire anyway.

- Confederate President Jefferson Davis was disappointed by Lee’s surrender, but he was truly bitter that Johnston gave up virtually all remaining Confederate troops in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida without being decisively beaten by Sherman’s army. Davis called the surrender “something unparalleled, without good reason or authority.”

- The McLean House was dismantled in 1893 in an attempt to move it to Washington, D.C. as a Civil War museum. It was never relocated, and was eventually reconstructed in the 1940s.

Learn More: The Appomattox Campaign

Related Battles

152

500