The Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863 was the largest cavalry engagement in American history and had a profound impact on the Gettysburg Campaign. The American Battlefield Trust has preserved more than 2,159 acres of this Virginia battlefield.

Fact #1: The Battle of Brandy Station was the largest cavalry battle in American history.

The Battle of Brandy Station came on the heels of a dramatic reorganization of the Army of the Potomac's cavalry. When Gen. Joseph Hooker replaced Ambrose Burnside in 1863, he aggregated previously disparate mounted units into a single cavalry corps. At last, the Federal horsemen were able to operate in numbers large enough to compete with their Confederate counterparts.

Thus, when the blue and gray troopers of both armies clashed on the field of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, a total of 18,456 horsemen became involved in the fighting. The ensuing action was the largest one day cavalry battle in American history.

It should be noted at an additional 3,000 Federal infantrymen were also present at Brandy Station, raising the total number of combatants to 21,456, and prompting some to argue that the 1864 Battle of Trevilian Station is the largest "all-cavalry" battle of the war. This technicality, however, belies the fact that even without these foot soldiers, 1,500 more cavalrymen fought at Brandy Station than at Trevilian the following year.

Fact #2: The Battle of Brandy Station was the opening engagement of the Gettysburg Campaign.

The fight at Brandy Station came a little over a month after the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May of 1863. Although Chancellorsville was a Confederate victory, it left the grey army considerably bruised and did little to change the strategic situation in Virginia. Recognizing the threats posed by the Union siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, the loss of Middle Tennessee, and the desolate state of the Virginia countryside, Robert E. Lee began an invasion of the North on the night of June 2, 1863. He hoped to at least find food and supplies for his starving troops, perhaps take pressure away from the other theaters of war, and at best force a peace by destroying the Army of the Potomac outside of Washington. The leading elements of Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s Cavalry Division moved into Culpeper in order to screen Lee’s march into the Shenandoah Valley and was in the vicinity of Brandy Station by May 15.

Fact #3: J.E.B Stuart held three reviews in the three weeks before the Battle of Brandy Station, frustrating his men and revealing his position to Union scouts.

On May 22, June 5, and June 8, J.E.B. Stuart assembled his horsemen on the southern banks of the Rappahannock River for inspection. Inspecting 10,000 troopers, however, required a significant amount of exertion from man and beast alike. Stuart was also fond of extravagance, and supplemented the reviews with a mock battle demonstration and a grand ball on June 5. Union officers observed these displays with great interest. The sound of cannon fire from the mock battle added to Union Gen. John Buford’s suspicions that the Confederate cavalry was concentrating near Culpeper, Virginia. After the June 8 review, the day before the battle, Confederate Gen. "Grumble" Jones speculated that, "no doubt the Yankees...have witnessed from their signal stations, this show in which Stuart has exposed to view his strength and aroused their curiosity. They will want to know what is going on and if I am not mistaken, will be over early in the morning to investigate." Jones was wrong about the Federal intelligence—Pleasonton remained convinced that Stuart was in Culpeper—but he would surely see the enemy in the morning.

Fact #4: Pleasonton's very complicated plan was based on a faulty premise

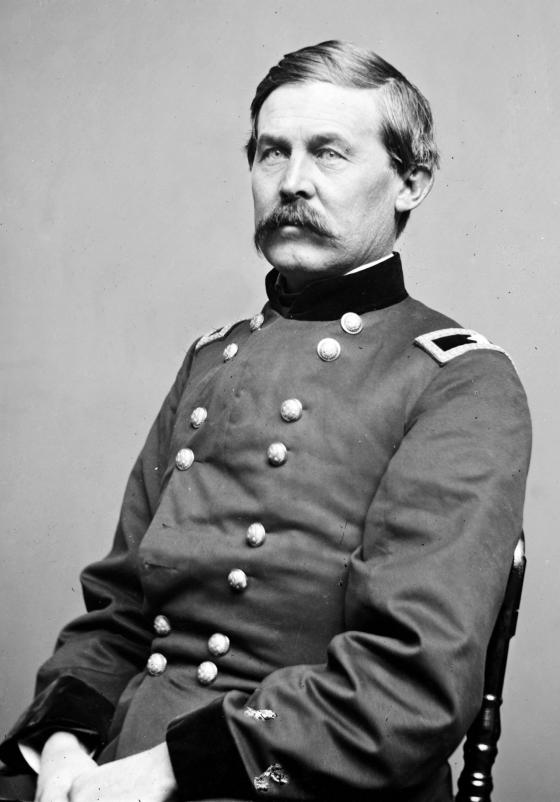

With his army preparing to move north, Gen. Lee ordered J.E.B. Stuart to screen the movement with his cavalry. Union officers suspicioned the sudden build-up of Confederate horsemen in the vicinity of Culpeper, leading Gen. Hooker and his ambitious new cavalry chief, Gen. Alfred Pleasonton to assume that Stuart was preparing for another of his trademark raids.

In order to "disperse or destroy" the rebels, Pleasonton planned a raid of his own. The Federal cavalry were to cross the Rappahannock at two places. John Buford's division was to cross the Rappahannock at Beverly's Ford; David McMurtrie Gregg's men would cross at Kelly's Ford. Once across, the two Yankee columns would reunite at Brandy Station—precisely where Stuart had massed his cavalry. The Union plan for June 9 unraveled the moment Buford's troopers splashed across Beverly's Ford.

Fact #5. Many of the Confederate troopers rode bareback during the battle.

The first Union column into battle forced a crossing at Beverly’s Ford at 5 A.M. The surprised Confederate pickets fled towards the main camp, firing their pistols in the air to announce their approach through the early morning fog. News of the attack reached most of the Southern troopers while they were still in bed. With enemy cavalry only two miles away, Stuart’s men were racing against the clock from the beginning of the fight. Many galloped towards the sound of guns without taking the time to saddle their horses or even fully dress. Nevertheless, they put together a stiff defensive line that checked the Union advance.

Fact #6. The first Union attack was disordered by the death of Col. "Grimes" Davis.

Almost immediately after crossing at Beverly’s Ford, Buford's lead element, under Col. Benjamin "Grimes" Davis ran into pickets of the 6th Virginia, who made every effort to retard the Federal advance. Very soon, the road from Beverly's Ford to St. James Church became engulfed in a congested hand-to-hand brawl. The Yankees' advantage in numbers soon began to tell, compelling the Virginians to withdraw. Before falling back, however, Lt. Robert Owen Allen of the 6th Virginia dashed upon Col. Davis, who was then in the act of rallying his troops. In a brief encounter, Davis was brought down with a bullet to the skull, mortally wounded. Although Davis’ men fought hard for their beloved commander, his death prevented the coordination necessary to swiftly punch through the Confederate line. Buford’s surprise attack became a grinding uphill battle as more Southern reinforcements joined the fray.

Fact #7. Pleasanton’s complex battle plan nearly broke down due to delays with his Kelly’s Ford column.

While Buford's troopers faced off against the main Confederate force at St. James Church, Gen. David McMurtrie Gregg's column was running behind schedule. First off, Col. Alfred Duffie's division was late to its rendezvous at Kelly's Ford. Then, Gregg's lead elements unexpectedly encountered Confederate pickets on the other side of the Rappahannock. Men of the 1st New Jersey snatched up the Rebel vedettes before they could sound the alarm, but time was ticking by. When the Pennsylvanian finally got his men across the river, he was ninety minutes behind schedule and Buford was already engaged. The Confederates in their front—North Carolinians under Gen. Beverly Robertson—compelled the Federals to make a longer march to Brandy Station. When Gregg finally (and unknowingly) arrived in Stuart's rear, a few shots from a single Confederate cannon convinced him that position on Fleetwood Hill was a formidable one. Gregg’s delay at the base of the hill allowed Stuart barely enough time to pull men out of the fight against Buford and beat back the new threat in his rear.

Fact #8. College friends Confederate Brig. Gen. William H.F. Lee and Union Lt. Col. Charlie Mudge fought each other at Yew Ridge.

With his frontal assaults at St. James Church failing, Buford decided to test the Confederate flank in the direction of Yew Ridge. In ordering this assault, he unwittingly pitted two old friends against each other. Gen. William Henry Fitzhugh "Rooney" Lee, the middle son of the Confederate commander, and Lt. Col. Charles Mudge had grown close as classmates at Harvard. Both had been oarsmen for the "Harvard Eight" crew squad and both were members of the “Hasty Pudding” social club. As the fighting on June 9 moved toward Fleetwood Hill, Rooney, leading a brigade of Confederate cavalry, faced off against Charlie’s 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. After repulsing several assaults, Rooney led a counter-attack on northern Fleetwood Hill and was wounded in the attempt. Charlie himself only had three weeks to live—he was killed while leading his own charge at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Fact #9. Brandy Station "made" the Federal cavalry.

After fourteen hours of grueling combat, Pleasonton realized there was nothing to be gained in continuing the fight and ordered his men to break off their attack. Stuart was left in possession of the field, but his men were in no shape to pursue. Although the battle can be considered a narrow Union defeat, it proved to have a great positive impact on the morale of the Northern horse soldiers. In the words of Stuart’s chief aide, "Brandy Station made the Federal cavalry." The Confederate cavalry commander was harshly criticized for allowing himself to be surprised and so nearly defeated on his own soil. The Richmond Examiner, perhaps inspired by the excessive reviews, went so far as to call the Confederate cavalry "puffed up." Nevertheless, Stuart deserves credit for conducting the battle well and winning, in spite of his ill-considered actions in the weeks previous. Lee’s infantry remained undetected as they marched towards the Shenandoah Valley.

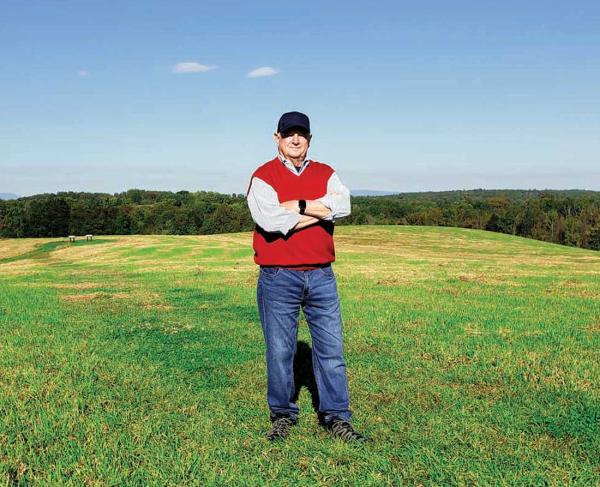

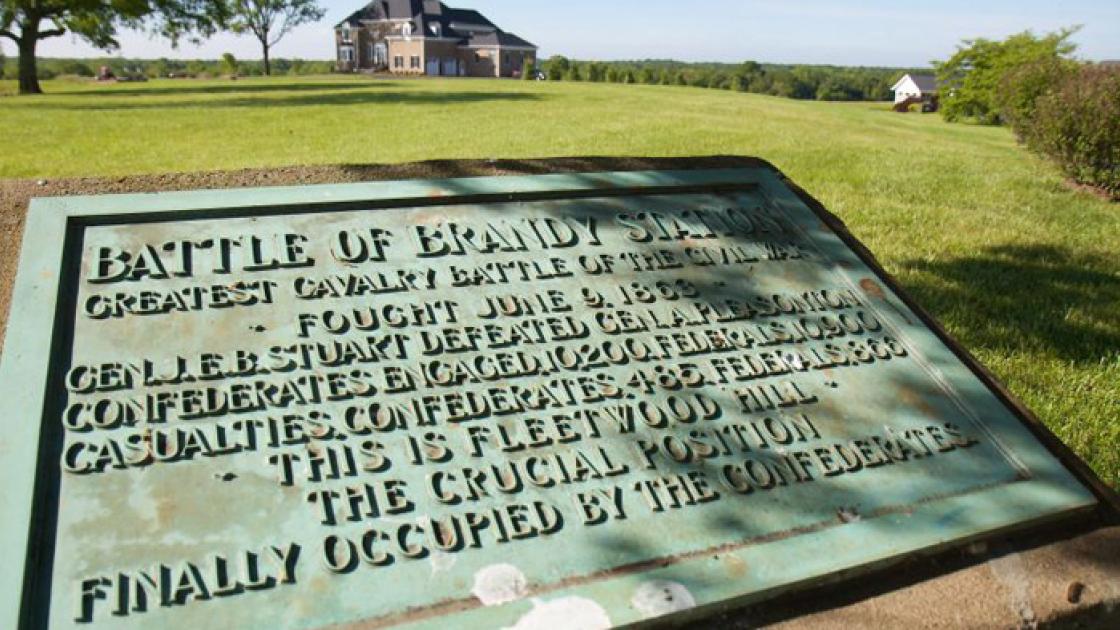

Fact #10. The American Battlefield Trust has saved more than 2,000 acres of the Brandy Station battlefield, including Fleetwood Hill.

In 2013, the American Battlefield Trust embarked on a venture to preserve 56 acres of the Brandy Station battlefield known as Fleetwood Hill. This property was the site of Stuart’s headquarters during the battle and was the site of the heaviest cavalry fighting to ever take place on the American continent. Thanks to a $700,000 grant from the Commonwealth of Virginia and the generosity of its members, the Trust was able to preserve this vital portion of America's largest cavalry battle.

Learn More: J. E. B. Stuart

Related Battles

866

433