10 Facts: Malvern Hill

To help you appreciate the importance of the Battle of Malvern Hill, please consider these ten facts about the battle.

Fact #1: Malvern Hill was the last of the Seven Days' battles.

On June 26, 1862, less than a month after taking command of the newly-christened Army of Northern Virginia, Gen. Robert E. Lee put his troops on the offensive. Over the next week, attacking Confederates drove their blue-clad counterparts from strong positions outside Richmond, unraveling Gen. George B. McClellan's scheme to capture the Confederate capital. Bloody fighting at places like Beaver Dam Creek, Gaines' Mill, Savage's Station, and, on June 30, Glendale altered the tempo and tenor of the war in Virginia.

The morning of July 1, 1862, found Lee's army once again threatening the retreating Army of the Potomac. The Yankees, however, held a strong defensive position on a gently sloping eminence just two miles north of the river, called Malvern Hill, inviting Lee to strike. The Confederates launched a series of uncoordinated assaults that ran headlong into the well-placed Federal artillery. When darkness fell, Lee's men had failed to dislodge the Yankees, who withdrew that night. Lee did not pursue; the Seven Days battles were over.

Fact #2: The Battle of Malvern Hill, was the first time during the Seven Days that the entire Army of the Potomac was united on the same field.

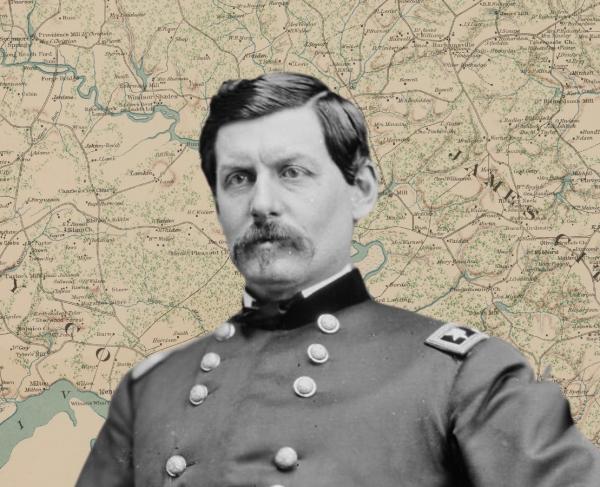

Lee's unexpected and violent assaults in the last week of June 1862, caught Gen. George B. McClellan completely off guard. Almost immediately, "Little Mac" determined that he could no longer take Richmond, and set his army into full-blown retreat to the James. Along the way, elements of the Army of the Potomac made brave stands, attempting to slow Lee's advance—but McClellan never deployed the bulk of his army to check the Rebel offensive.

On July 1, 1862, all five Federal corps were in the same place at the same time for the first time that week. The open nature of Malvern Hill itself allowed the Yankees to deploy the entirety of their immense army in a way they hadn't since the seven days began. However, elements of three corps were detailed to guard the Federals' right flank, and consequently, saw no action. Even with all his troops in one place, McClellan did not utilize his whole army.

Fact #3: General McClellan did not direct his army during the battle.

Once McClellan determined to withdraw, the Federal commander seemingly abdicated all responsibility for managing his army while they struggled to cope with Lee's relentless advance. He spent most of June 30 aboard the gunboat Galena while the Army of the Potomac staved off disaster at Glendale.

While McClellan was on the field during most of the Battle of Malvern Hill, his role not much more active that it had been previously. In the early hours of July 1, McClellan met with his favorite subordinate, Gen. Fitz John Porter to discuss the disposition of his troops, before again retiring to the Galena—presumably to prepare the army's supply base at Harrison's Landing. The commanding general returned to the field later, but was content to let Porter and his other corps commanders manage the battle on their own. Unlike the battle the previous day, however, McClellan's subordinates had a clear view of the battle plan, and, with Porter serving as de facto army commander, the Young Napoleon could be assured that plan would be carried out.

Fact #4: Faulty maps significantly delayed the Confederates’ arrival at Malvern Hill.

To strike the Federals a Malvern Hill, Lee needed to mass the disparate elements of his army. Lee dashed off orders to his commanders, directing them to approach Malvern Hill by two main axes of advance—Carter’s Mill Road and Willis Church Road. Unfortunately for the Confederates, the map their commanding general used when planning this relatively simple maneuver incorrectly labeled the Willis Church Road, the "Quaker Road." This, it seems was a colloquial name for a number of roads which, presumably, lead to a nearby Quaker meeting house. Thus, local guides shepherding Lee’s troops led them down the wrong road and away from the battlefield. The confusion was eventually sorted out, but caused the Confederates an hours-long delay.

Fact #5: The "farcical" performance of the Confederate artillery allowed the Union artillery to dominate the battle.

Taking advantage of high ground north of Malvern Hill, Robert E. Lee ordered the placement of two "grand batteries"—massive arrays of his artillery—in support of the left and right wings of his army. Lee believed fire from these massed cannon would converge on the Union center and weaken the Yankees' ability to resist the force of the infantry assault that was to follow.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, logistical problems kept all but a fraction of Lee's artillery from ever reaching the field, and those that did were put into action piecemeal. Embittered division commander Gen. Daniel H. Hill went so far as to call the performance of the Confederate batteries "most farcical." Union artillery—as many as 40 cannons massed in the center of the Federal position—made quick work of suppressing their Rebel counterparts. With the Confederate guns no longer a major factor, Yankee gunners directed their attention to the lines of gray-clad infantry advancing up the slopes of Malvern Hill, thus dominating the battle.

Fact #6: The nature of the terrain forced the two wings of Lee's army to wage two separate battles.

The elevated plateau known as Malvern Hill consisted of large open farm fields ranging from the steep slopes of Malvern Cliffs on the west to the Western Run, on the east. The Willis Church Road, which runs roughly north to south, bisected the Union position on the crest of the hill. To the west of this road, the land is a gentle rise from the northern portion of the field to the crest of Malvern Hill, near the Crew House. The Confederates on this portion of the field under Benjamin Huger and John Magruder made their advance while being constantly exposed to Federal artillery and small arms fire which devastated their ranks.

The eastern portion of the field, "Stonewall" Jackson's front, is broken by awkward projections of woods and steep swales. These features allowed the Jackson's men to advance toward the Union line out of sight of the Federal gunners on the crest of the hill, but they were also completely cut off from their comrades west of the road. Unable to see—let alone support—one another the two wings of Lee's army were left to fight separately.

Fact #7: Despite the dominant role of Union artillery, Confederate infantry inflicted significant casualties on the Federals.

Col. Henry J. Hunt's well-placed Union artillery rained great destruction upon the Confederate infantry, but Lee's troops continued their advance, even getting into effective range for their rifled and smoothbore muskets to endanger the Union gunners. As a result, nearby Yankee infantry—such as Charles Griffin's Fifth Corps brigade or the Irish Brigade—was rushed forward to drive off the Rebels and protect their artilleryman from small arms fire.

This was especially true on Stonewall Jackson's front, where the topography allowed the Confederates to advance out of sight of the Union artillery. Gen. Darius Couch's division of blue-clad foot soldiers—including a brigade of New Yorkers under Gen. Daniel Sickles—rushed down the slope to check this advance.

This challenges the simplistic view of Malvern Hill as merely a battle between Confederate infantry and Union artillery. However, as historian Bobby Krick points out, given the negligible role played by the Confederate artillery during the battle, it is more than likely that a good portion of the more than 3,000 Union casualties at Malvern Hill were the result of these infantry fights.

Fact #8: The much-heralded Irish Brigade earned its reputation at Malvern Hill.

Since its formation, the Union army's Irish Brigade had received a great deal of attention from the Northern press, much of it self-promotion on the part its commander, Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher. However, apart from a handful of troops who had been engaged at First Bull Run, most of these Irish soldiers had yet to see significant action. On July 1, 1862, that began to change.

As Confederate attackers came closer and closer to the Federal gunners on Malvern Hill, Union infantry were sent forward to drive them back. Among the units called upon for this duty was the Irish Brigade, which was thrust into battle late in the day to stave off the last Confederate attacks at Malvern Hill. From that moment on, the Irish Brigade's began to back up its early war hype with solid battlefield performances.

Fact #9: Though victorious, the Federals withdrew after the battle, effectively ending McClellan's campaign to take Richmond via the Peninsula.

The Union victory at Malvern Hill, while a morale booster for the Army of the Potomac, did nothing to alter the circumstances facing the men in the ranks of the Federal army. Their back was to the James River, their supply lines vulnerable, and they were exhausted from a week's worth of hard marching and heavy fighting. So, despite an excellent performance, early the next morning the Yankees continued their retreat to Harrison's Landing, twelve miles away. The campaign to take Richmond via the Peninsula was over.

In fact, George McClellan had made up his mind to abandon this movement against Richmond as early as the night of June 26. McClellan, who called the retrograde motion of his army a "change of base," lavished praise upon his army for their "survival against adversity." Stopping the Confederates at Malvern Hill merely allowed the Yankees the chance to complete their retreat to the safety of their supply base, and deny Lee the chance to destroy the Federals once and for all.

Fact #10: The American Battlefield Trust has saved hundreds of acres at Malvern Hill.

Over the years, the American Battlefield Trust and its partners have preserved hundreds of acres of the Malvern Hill battlefield. Add these to the 130 acres previously owned by the National Park Service, and visitors can now walk the entire length of the Confederate attack and appreciate just how greatly the ground itself impacted this important 1862 battle.

Learn More: Seven Days Battles

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

2,100

5,600