American military history is infused with examples of amphibious military operations. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, the American merchant marine was second in size only to that of England. The move to create a world-class navy was only natural.

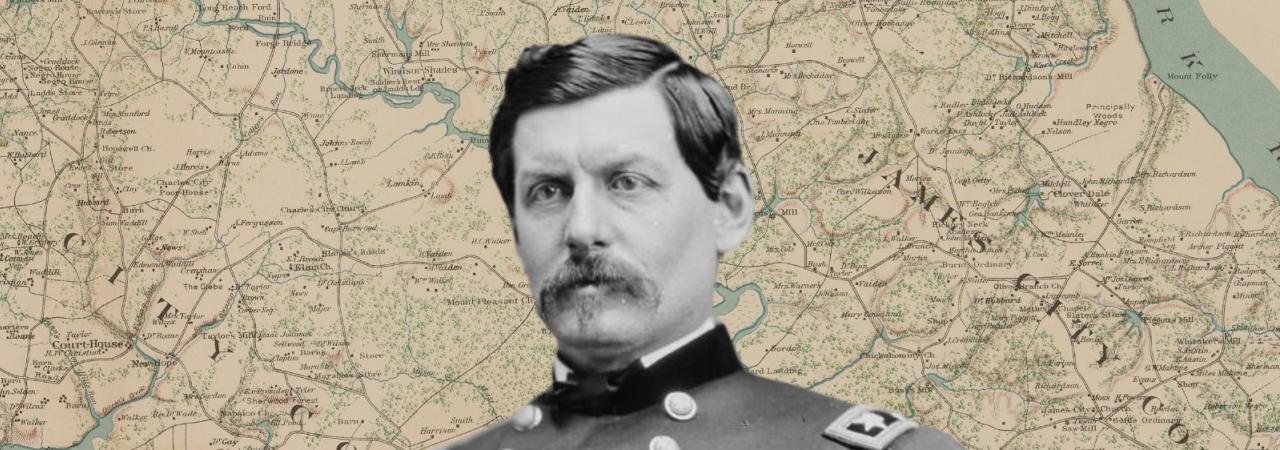

While most American amphibious operations were successful, Union General George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign of 1862, which aimed to end the Civil War by capturing the Confederate capital of Richmond, stands out as a notable failure. The lack of a results-oriented campaign with clear, achievable steps for implementation hampered the successful completion of the Peninsula Campaign and prevented an expedited ending to America’s bloodiest war.

McClellan’s initial thinking was correct. Taking advantage of the initiative and maneuverability granted by the Union’s exterior lines, he could ferry his army from Washington to a site on one of Virginia’s several peninsulas to flank the divided Confederates, preferably landing at Urbanna. By doing this he would be utilizing the Union’s formidable navy to keep his troops supplied. The Confederates were already entrenched outside Washington, and he used the ability of the attacker to pick the place of battle, preferably where the Union’s advantages could be brought to bear. Additionally, an amphibious operation was greatly preferable to marching overland from Washington, given the hostile nature of the country and the numerous natural barriers.

Unfortunately for McClellan, General Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, felt overexposed and shifted his forces south, negating the advantage of any Union landing at Urbanna. Despite this, McClellan pressed to go ahead with his plan, selecting a new landing site at Fort Monroe on Virginia’s lower peninsula. Such a plan afforded a few additional advantages. Firstly, while he would no longer be flanking the Confederates, “gunboats could protect his flanks” as he advanced up the peninsula. Secondly, Fort Monroe was already under federal control, providing a secure base from which to direct his campaign.

President Lincoln was concerned about leaving Washington open to attack and stated that McClellan was merely “shifting and not surmounting” the inevitable head-on encounter with Confederate forces. Hypothetically, the Confederates could make use of their nimbler interior lines, and quickly mass their own troops to oppose the Army of the Potomac.

McClellan’s plan began to unravel when his inability to effectively use the navy became apparent. All involved—rebel and Yankee alike—understood that the success of his plan depended upon the ability of the Union navy to supply and support his army. The US Navy would be unable to do so if faced with Confederate naval opposition. With this in mind, McClellan’s subordinate generals demanded that naval superiority be a prerequisite for landing troops. While McClellan acquiesced, he never acted or even made a plan to ensure that the federal navy went unopposed.

The chief object of concern here was the CSS Virginia, a former US frigate converted into a practically impenetrable iron barge that terrified the Union blockade in Hampton Roads. After the USS Monitor, another ironclad, fought the Virginia to a draw on March 9th, McClellan felt he could safely land troops and convinced the navy to do so. However, the situation was not solved: a delicate naval stalemate evolved in which federal commanders were reluctant to conduct any naval operations further up the James River outside the protective screen of their blockade and the Monitor. From the outset of his campaign, McClellan was denied one of the key advantages of undertaking it in the first place.

Union forces began landing at Fort Monroe on March 24th; on April 4th, the army was fully massed and McClellan set out for the first line of Confederate defenses. But without the naval support on either flank, his army quickly found itself deterred by a small Confederate contingent commanded by General John B. Magruder, who would have retreated had the federal navy advanced up either flank, per his field orders. The ill-considered use of the navy thus helped set McClellan’s campaign back by weeks.

The next major failure in McClellan’s execution was a lack of reliable intelligence. He relied almost exclusively upon the famed private-eye Allan Pinkerton, who was woefully ill-suited for collecting military intelligence in the field. To compound problems further, McClellan’s “handsome Coastal Survey maps were dreadfully inaccurate”.

As his army moved toward the Confederate entrenchments on April 4th, it quickly became apparent that the Warwick River was not a mere creek as indicated on the Union maps; rather, it was a marshy morass directly in front of the Confederate positions. Furthermore, the Confederates had dammed parts of the river, creating impassable lakes, and concentrated their artillery on the few remaining open paths.

Intelligence errors plagued the general on another front, too: troop numbers. Whatever the battle, no matter the circumstance, McClellan was always convinced that Confederate forces outnumbered his own. His unwavering belief in this unreality was only reinforced by the sycophantish Pinkerton, who fed McClellan a rumor from a captured Confederate soldier “that Johnston was arriving with 100,000 soldiers.”

In reality, the Confederate defenders initially numbered only 13,000 to the McClellan’s 121,500. The general’s firm belief that he faced substantial opposition made him reluctant to commit his troops to a pitched, open battle, settling for a long siege instead. Nor did it help that he was denied access to reinforcements in the form of McDowell’s corps, which continued to protect Washington, D.C. instead of joining the campaign. Moreover, the siege of Yorktown and the Warwick line provided the Confederates additional time to concentrate and mass their defenses. The original defenders were augmented each day by new units committed in piecemeal fashion from around Virginia. By April 14th, 31,500 Confederate troops were either defending the Warwick line or on their way to do so. During this period, defensive lines were under construction further up the peninsula near Williamsburg, and still, additional lines were being built around Richmond.

By besieging Yorktown McClellan provided the Confederates time to develop a primitive defense-in-depth, a strategy masterminded by the Germans during the First World War which ensures that even a military steamroller is eventually sapped of momentum. The Confederates had the time they needed to negate the effect of McClellan’s overwhelming forces and instead fight a form of war that maximized their own advantages.

The Confederates understood McClellan’s cautious nature as a commander. Taking advantage of this, General Magruder continuously kept his troops on the move to give the impression of a large field force. In just one example, he marched a single unit along a road visible to Union observers and then into a thicket where their movements could not be perceived. They would then go back to the start of their march, unseen, and move along the same road. The whole operation acted as a conveyor belt. McClellan was thrown by the tactic, which appeared to confirm his belief that the Confederates outnumbered him.

However, while Magruder did all he could to trick McClellan and fortify his position, his orders to delay came from General Robert E. Lee, who was responsible for coordinating Confederate strategy against the Union in the east. As soon as the Union plan became apparent, Lee intrinsically understood that time was the Confederates’ most important resource. He “believed that invaluable time could be gained by delaying McClellan [on the lower peninsula] as long as possible.” Quickly forming a countering plan, Lee sprang into action, navigating the tricky politics of the Confederate capital and high military command to build up Confederate forces in Richmond and on the peninsula. Lee also personally oversaw the construction of batteries at Drewry’s Bluff, a promontory overlooking the James River approach to Richmond.

Thus, Lee “benefitted by the extreme caution of his opponent” to openly confront the Confederates, using his nimble interior lines to mass his forces. By the time McClellan did reach Richmond, he was faced with the bulk of Confederate forces in Virginia.

Back on the peninsula the Confederate forces, now directly commanded by Johnston, held out as long as they could—as soon as McClellan had brought up his siege guns, Johnston abandoned his position and started a headlong retreat towards Richmond. Federal forces pursued, engaging the Confederate rearguard at Williamsburg on May 5th. The battle was indecisive, and the Confederates continued their retreat, checking a federal amphibious landing on their York flank along the way. As the advance continued, federal forces slowed and McClellan failed to “grasp the tactical opportunities made available by the Confederate retreat.”

As noted by Carl von Clausewitz, success in any campaign is often not determined by the outcome of a single battle or confrontation, but rather by the ability of the advancing general to follow up on strategic or tactical victories and ultimately rout the opposing force. McClellan displayed neither the vigor nor the organization needed to exploit his forward momentum, again bogging down his campaign.

Matters in Hampton Roads and on the James would not be decided by McClellan, but by Lincoln, who took control of the situation during his visit to Fort Monroe. Lincoln was “amazed to find that McClellan had made no provision for the capture of Norfolk,” which was now open to attack following the rebel retreat on the peninsula. Further, occupying Norfolk would deny the Confederates the Virginia, opening the James River to naval operations.

Norfolk was easily captured on May 10th and the Confederates scuttled the Virginia, allowing a flotilla of Union vessels to be sent up the James River towards Richmond. However, they failed to pass the Confederate gun emplacements on Drewry’s Bluff. Had they done so, the campaign would have been over in the Union’s favor. His forces passed the point Union transports could land troops on the York and the Union fleet unable to reach Richmond, McClellan again denied the forward support of the navy.

The situation on Drewry’s Bluff may have been solved in McClellan’s favor had he simply landed a modest detachment from his sizable army across the river and assaulted the position on land—it was only defended by a single brigade.

At last, McClellan’s forces reached the outskirts of Richmond. Confronted with yet another line of Confederate entrenchments along the Chickahominy River, McClellan opted to turn northward, which would allow him to connect with the units under General McDowell before driving south to take Richmond. McClellan was confronted again with bad geography: taking a northern approach to Richmond involved negotiating the bogs surrounding the Chickahominy River, which was swelled following heavy rains. Making matters worse, while McClellan needed to cross the river, his superiors ordered him to keep a substantial portion of his army north of the river to link up with McDowell. His forces were now divided on either side of the river, a tenuous position the Confederates gladly exploited. With a three-pronged attack, Johnston sought to take each federal corp one at a time with the entirety of his own force. Ironically, the reinforcements from McDowell—on whose account McClellan’s forces were exposed—never arrived as they were redirected to the Shenandoah.

While Johnston’s plan ultimately descended into confusion, Robert E. Lee took direct command after the general was badly wounded and launched aggressive strikes against the isolated forward elements of McClellan’s army in a series of battles collectively termed the Seven Days’ Battle, eventually reversing momentum and pushing Union forces back down the Peninsula.

The Battle of Malvern Hill offers an example of what might have happened had McClellan simply chosen to confront the Confederates head-on from day one. Against the now massed, whole, undivided Army of the Potomac, the tenacious Confederate offensive crumbled, resulting in massive casualties for the Confederates and saving the Union army from a rout.

General McClellan, through his failure to effectively implement his sound strategic ideas, granted the Confederates room to operate in a way that allowed them to maximize their own unique advantages—a condition never permitted by the best of tacticians or strategists. Following further strategic blunders during the Battle of Antietam, he was dismissed by President Lincoln. However, General McClellan left his country with a well-trained, veteran army, ensuring that the Union at least had its means of preservation. Several years of bloody fighting would elapse until the Union again had a path to Richmond, this time led by a commander sure to deny the Confederates every advantage possible all while utilizing federal numeric and technological superiority.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

2,283

1,560

369

24

2,100

5,600