10 Facts: Sailor's Creek

Expand your knowledge of the Battle of Sailor's Creek with these ten facts about the Battles of Sailor's Creek.

Fact #1: The Battle of Sailor's Creek was actually three separate engagements.

While often thought of as a single engagement, three distinct actions make up what is commonly referred to as the Battle of Sailor's Creek. First, the Confederate rear guard under Gen. John Gordon was forced to make stand against the Union Second Corps under Gen. Andrew Humphreys on the James Lockett Farm. To the south, the Union Sixth Corps under Gen. Horatio Wright, bombarded then assaulted Gen. Richard Ewell's two divisions along Little Sailor's Creek near the James Hillsman Farm. Lastly, Confederate divisions under Gen. Richard Anderson squared off against Gen. Wesley Merritt's three divisions of Union cavalry in the vicinity of Marshall's Crossroads.

These three disparate battles occurred almost simultaneously with one another, thus giving the illusion of one large general engagement. However, the fight at the Lockett Farm between Humphreys and Gordon took place two miles to the northwest of the other two engagements. And though the Wright-Ewell and Merritt-Anderson fights were closer to one another geographically, neither of the Federal commanders made a concerted effort to cooperate with the other. More importantly, the two Confederate corps there were fighting practically back-to-back and, thus, unable to render aid to one another.

Fact #2: The Battles of Sailor's Creek are known by various different names and spellings.

As with many Civil War battles, historians do not always agree on what to call the fighting that took place on April 6, 1865. Firstly, the stream over which the two armies contended was not Sailor's Creek, but rather one of its tributaries, called Little Sailor's Creek. Secondly, the battlefield is broken into three geographic areas—the Lockett Farm, the Hillsman Farm, and Marshall's Crossroads—each of which can be regarded as a battle in its own right.

The issue most familiar to students of the Civil War, however, is one of spelling. Though the earliest maps of the area label the stream which gives the battle its name as "Sailor's Creek," by the 19th Century a number of variations of that name (Sailer's, Saylor's, and Sayler's) had become common, and even appeared on some wartime maps. As a result, many prominent historians have used what they believed to be the historic name for the stream and called the battle, the Battle of Sayler's Creek. The National Park Service and the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission, however, have established "Sailor's Creek" as the proper spelling of the stream and the battles that raged over it on April 6, 1865.

Fact #3: A Union roadblock at Jetersville prompted Lee to move his army toward Farmville, beginning the chain of events that led to battle on April 6, 1865.

Following the fall of Richmond and Petersburg, Gen. Robert E. Lee's primary objective was to get his army into North Carolina and unite with Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate force there. To get there, Lee directed his armies to converge at Amelia Court House to resupply and then move toward the railroad hub at Danville. To thwart this maneuver, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant sent the bulk of his effective force—infantry from five corps and Gen. Philip Sheridan's cavalry—to pursue Lee and block the road to Danville.

Rain-swollen rivers and mislaid food stores delayed Lee's army and allowed the Federals to gain ground. While the Confederates were scouring southside Virginia for food at Amelia, elements of the Union Fifth Corps managed to get in front of Lee at Jetersville. With Federal entrenchments blocking the road to Danville, Lee was forced to find an alternate route. He ordered his army to move west on the evening of April 5, setting in motion the series of events that led to the fighting in the valley of Sailor's Creek.

Fact #4: Federal cavalry caused three corps of the Army of Northern Virginia to become isolated, thus setting the stage for the fighting along Sailor's Creek.

Gen. Phil Sheridan's Union cavalry had been hounding Lee's army since the Appomattox campaign began. On April 6, 1865, the Yankee horsemen rode parallel to the Confederates' line of retreat and made a series of hit and run attacks as they made their way from Amelia Court House to Farmville. Gen. George Crook's division of Federals made one such effort at Holt's Corner which compelled the Confederate corps under Gen. Richard Anderson, Gen. Richard Ewell and Gen. John Gordon to halt their march and make preparations to repel a general assault. When no assault was forthcoming, the Confederates renewed their march. The halt, however, had put two miles between Anderson's corps and the nearest Confederate unit to the west. Making matters worse, Union. Gen. George Custer observed this gap and blocked the road with his division of cavalry. Anderson and the two corps behind him were now cut off from the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Fact #5: General Ewell's Confederates had no operational artillery.

Following the halt at Holt's Corner, Gen. Richard Ewell and his fellow generals Richard Anderson and John Gordon made a decision that they hoped would protect the army's supplies. The supply wagons were rerouted to the north, with Gordon's corps following for protection. Meanwhile, Anderson and Ewell continued westward to link up with the rest of the Confederate force. Any ammunition in the train with Gordon's force would be lost to Anderson and Ewell. If that weren't enough, around 2PM, Gen. George Custer spied an unprotected ordinance train just ahead of Anderson's troops at Marshall's Crossroads, which Custer's Yankees snatched up. Thus, when Union artillery opened fire on Ewell's troops later that day, the Confederates had no artillery with which to answer the Federal bombardment.

Fact #6: Many of the Confederate troops were garrison troops from Richmond.

Of the three small Confederate forces engaged in the Battles of Sailor's Creek, one of them, that under Gen. Richard Ewell, was composed primarily of men that had spent the majority of their service guarding the Confederate capital of Richmond. Among these, the heavy artillery units under Gen. Stapleton Crutchfield are perhaps the most notable. These troops had been trained to both operate the heavy guns in Richmond's forts and to carry rifles and fight like infantry. Despite their relative inexperience, however, these garrison troops displayed great bravery while facing off against the Federals on April 6, 1865.

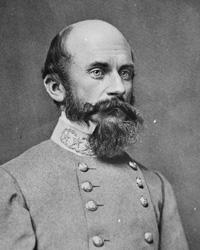

Fact #7: Eight Confederate Generals were captured during the battle, thus ending the fighting.

As the Confederate defense began to crumble under the weight of the Federal attacks on April 6 and Confederate troops began to surrender en masse, so too did many of their commanding officers. A total of eight Confederate generals ended the war on April 6, including some of the Confederacy's most well-known commanders. Richard S. Ewell, Joseph B. Kershaw, Montgomery Corse, Eppa Hunton, Dudley M. DuBose, James P. Smith, and Seth Barton all became prisoners that day. But perhaps the most notable capture that day was Gen. George Washington Custis Lee, Robert E. Lee's eldest son.

Fact #8: Lee's army lost 1/4 of its force on April 6, 1865.

When the dust settled on April 6, more than 8,800 Confederates had become casualties in the last major battle of the war in Virginia. Of those, roughly 7,700 had been captured or surrendered--one of the largest surrenders of an army without proper terms during the whole war. This was a substantial blow to Lee's already crippled army, which that morning had numbered scarcely 30,000 effectives.

Fact #9: After Sailor's Creek both armies knew the end was near.

Following the series of debacles along Little Sailor's Creek, generals from both sides were aware that the end of the war in Virginia was in sight. Gen. Robert E. Lee, watching his army disintegrate at Marshall's Crossroads, remarked to Gen. William Mahone, "My God! Has the army dissolved?" To further underscore the scope of the disaster, Lee wrote to President Jefferson Davis that "a few more Sailor's Creeks and it will all be over."

On the Union side, the never bashful Gen. Philip Sheridan wrote of his success to General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant. "If the thing is pressed," wrote Little Phil, "I think that Lee will surrender." Sheridan's report reached President Lincoln who responded by saying, "Let the thing be pressed." The next morning, April 7, Grant sent a note to Lee, thus opening the dialogue that led to Lee's surrender on April 9.

Fact #10: The Civil War Trust has saved hundreds of acres at Sailor's Creek.

Over the years, the Civil War Trust has preserved multiple important portions of the Sailor's Creek battlefield. Though most of this land is near the Hillsman Farm, with the help of our members were have protected portions of the historic Lockett Farm, and Marshall's Crossroads. Much of the land we have saved has since become part of the Sailor's Creek Battlefield Historical State Park.

Learn More: Appomattox Campaign