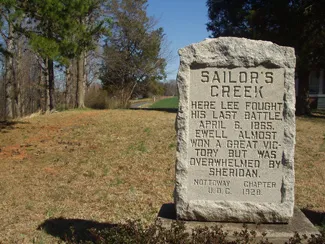

The Battles of Little Sailor's Creek

It had been one disaster after another for Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia during that first week of April 1865. On the 1st, at a road junction in Dinwiddie County known as Five Forks, Federal cavalry and infantry smashed a similar force protecting the last supply line into Petersburg, the South Side Railroad. This southern command was composed of foot soldiers led by Generals George E. Pickett and horsemen by Fitzhugh Lee. This group was told by Lee to “hold Five Forks at all hazards,” since this important road junction was just south of the railroad and the avenue of approach to it. When word reached General Ulysses S. Grant about the victory there by Generals Philip H. Sheridan and Gouvernor K. Warren, he gave the order for a series of assaults on the main Confederate line defending the long sought after railroad center of Petersburg. By early morning of the 2nd of April, Grant’s columns successfully broke through Lee’s defenses, virtually dividing his forces in two. Sadly this day the Confederacy would lose one of its finest corps commanders, General Ambrose Powell, in a brief but deadly confrontation with two Federal soldiers. The rest of the day would see numerous clashes in different sectors of the lines and the names of Fort Mahone, Fort Gregg and Sutherland Station became battle honors for the men of both sides. That night, Lee would give orders to withdraw his forces from the three fronts he protected for almost nine and one-half months.

General James Longstreet’s First Corps, along with General Richard S. Ewell’s Reserve Corps, would leave the Richmond defenses and cross to the south side of the James River. General William Mahone, whose division held the Howlett Line between the James and Appomattox Rivers across Bermuda Hundred, moved inland to Chesterfield Court House. General Lee, with General John B. Gordon’s Second Corps and the remnants of Hill’s Third Corps, passed through the “Cockade City” and crossed to the north bank of the Appomattox. Finally, those cut off at Five Forks and by the breakthrough in the lines west of the city, would stay south of the Appomattox River. The rendezvous point of all these contingents of Lee’s army would be Amelia Court House on the Richmond and Danville Railroad, about 30 miles to the west.

Initially, plans had been made for the evacuation of Richmond and Petersburg with the idea that Lee would take his army to North Carolina and join up with that of General Joseph E. Johnston’s operating near Raleigh. To do this they would obtain supplies and subsistence at Amelia, then would follow the railroad toward Danville and the border. Making an all night march on the night of April 2nd-3rd, Lee was able to gain a lead on the Federals, who would take most of the day in occupying the newly captured cities of Petersburg and Richmond.

The first obstacle that confronted the Southern troops on the march was that most would have to recross the Appomattox River in order to get to Amelia. Plans had been previously made for three bridge crossings, one at Genito, one at Goodes and the other at Bevills. Unfortunately spring flooding made Bevills impassible and the failure to get pontoons to Genito caused complications there. Eventually the troops at the latter point, those of General Ewell, would plank the Richmond & Danville Railroad bridge near Mattoax to cross. Most all other troops then had to pass over the regular and pontoon bridges at Goodes. By the morning of the 4th, the Confederate troops were beginning to fill the streets of the county seat village. As Lee and his officers reached the area of the railroad station, they opened the cars to find large amounts of ordnance supplies but no food. Knowing his men could not go on without subsistence, he issued a proclamation to the local citizens for help. At the same time he ordered supplies sent up the railroad from Danville and awaited the arrival of the rest of his forces, particularly those coming from the Richmond defenses who were waylaid in crossing the Appomattox.

Grant, besides moving into Richmond and Petersburg, also began preparing his remaining troops for the pursuit. His numerous corps would be south of the Appomattox River and would stay as thus. Sheridan’s cavalry were already pressing the Confederates who escaped the debacle at Five Forks and continued to fight rearguard actions with the enemy at such places as Scott’s Crossroads, Namozine Church, Deep Run and Tabernacle Church. Seeing that the Confederates were falling back into Amelia Court House, it now became apparent where Lee’s army was locating itself. Realizing that the goal must be Danville and North Carolina, the troopers rode off to cut the railroad in front of Lee. If they could achieve this, and get enough infantry there to support them, Lee’s plan would be thwarted.

As the forage wagons began returning to the Court House on the 5th, Lee saw little arrive in the form of supplies. He had failed to feed his army, and, more importantly, lost his days’ lead on Grant’s forces. He later lamented that “this delay was fatal and could not be retrieved.” His commanders then set about putting the army in motion, marching down the railroad toward Danville and its next station, Jetersville. Lee would eventually join the van of the column after hearing skirmish fire in the front. A mounted cavalry officer in the distance proved to be his son “Rooney” (William Henry Fitzhugh) as General Lee and General Longstreet rode into the woods near Jetersville. There appeared to be trouble up ahead that might possibly change the plans of going directly to North Carolina. General W. H. F. Lee reported to his superiors what he had reconnoitered: dismounted Federal cavalry was entrenched across the road and infantry was surely to follow. Should Lee attack and clear the road or try another alternative? Because of the lateness of the evening and the fact that Lee’s column was well spread out, the general decided to change his original plans. He would make a night march, passing to the north of the Federal left flank, and head west for Farmville on the South Side Railroad. There he could obtain supplies for his army, then head south, intersecting the Danville rail line near Keysville. To be successful, once again he would have to out distance Grant’s army.

As the Confederates groped through the night, they had to first ford Flat Creek then pass through the country resort of Amelia Springs. As the morning of the 6th dawned, the troops had nearly bypassed the unsuspecting Federals, when the crack of skirmish fire was heard across the creek. Elements of Union infantry observed the final contingents of Lee’s column moving along the opposite ridge and immediately set out in pursuit. It was the beginning of what was later referred to by some historians as the black day of Lee’s army.

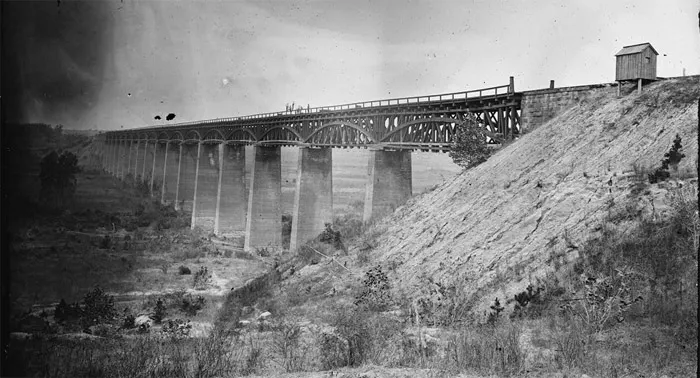

The route the Confederates followed ran through a couple of hamlets before reaching Farmville, twenty-three miles away. The first was merely a crossroads called Deatonsville. From there the road passed through bottomlands traversed by Little Sailor’s Creek (current spelling Sayler’s), a tributary of the Appomattox River. Continuing westward, the South Side Railroad was reached at Rice’s Depot and from there the road ran directly into Farmville. The terrain throughout the area was generally rolling being slashed occasionally by various watercourses: Flat Creek, Big and Little Sailor’s Creek, and Sandy and Bush Rivers. Bordering to the north was the generally unfordable Appomattox River with its only crossings being at Farmville and three miles northeast at High Bridge (South Side Railroad trestle).

In the van of Lee’s column was General James Longstreet’s combined First and Third Corps, followed by Richard Anderson’s small corps of Generals Pickett and Bushrod Johnson’s divisions, then General Richard S. Ewell’s Reserve Corps made up of Richmond garrison troops, the main wagon train, and finally General John B. Gordon’s Second Corps acting as rearguard. It would be the Federal II Corps that spied Gordon’s troops passing near Amelia Springs at daybreak on the 6th and set out in immediate pursuit. Following on a parallel road to the south of the one that the Confederates were moving on was fast riding blue cavalry under General Sheridan. Close behind them would be General Horatio G. Wright’s VI Corps leaving from their trenched position at Jetersville.

The showery morning march of Longstreet was broken when the general received news of a bridge burning party of Union cavalry and infantry, about 900 strong, heading for the High Bridge. They had been sent from General Edward O. C. Ord’s Army of the James at Burkeville Junction where the Richmond & Danville and South Side Railroads crossed. Longstreet immediately dispatched General Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry to chase then down and prevent any destruction to this important crossing. Not only were they successful in doing so, they completely captured the lot, although at the high cost of General James Dearing’s life (mortally wounded) in some brief but savage fighting. He would be the last Confederate general to die in the war.

While Longstreet was arriving at Rice’s Depot, the rear of his column became separated from the head of Anderson’s Corps. Observant Federal cavalry, led by General George A. Custer saw their chance to wreak havoc. Charging into the gap, the troopers were able to put up a roadblock in Anderson’s front. At the same time, Ewell, realizing that further attacks were imminent, decided to send the wagon train on a more northerly route than the one the army was traveling. This he did at a local crossroads called Holt’s Corner about a mile northeast of the Little Sailor’s Creek crossing. Gordon, being heavily pressed by General Andrew A. Humphreys II Corps, followed the trains, as did the Federals. The stage was being set for the Battles of Little Sailor’s Creek.

The area where Anderson decided to make his stand was at a crossroads bounded by the Harper and Marshall farms. This was about one mile southwest of the road crossing over the creek. As the wagon train was departing the main column, Ewell took his force to the southwest side of the creek. Here he formed a battleline on a ridge parallel to the creek facing northeast, over looking the Hillsman farm. Shortly, the opposite high ground would be swarming with Federals from the VI Corps who were quickly arriving on the scene. General Wright immediately set about emplacing his artillery, which began firing on the Confederate line. Ewell, devoid of any artillery, could not reply as his men hugged the ground to escape the flying shrapnel. It was now about quarter past five in the evening.

Simultaneous with this, Sheridan’s subordinate, General Wesley Merritt, was preparing the three cavalry divisions for an assault on Anderson. These horsemen were commanded by General George A. Custer, General Thomas Devin and General George Crook. Anderson’s men, a mile in front of Ewell, readied themselves by building breastworks out of fence rails as they dug in along the road. They did have artillery and would soon put it to use against the mounted troopers.

After a half hour bombardment, Wright’s men (two divisions under Generals Truman Seymour and Frank Wheaton) formed their battleline and advanced to the creek. Because of a spring freshet, Little Sailor’s Creek was out of its banks and ran from two to four feet deep. The men crossed this with great difficulty, reformed their line, and began the assault upon the Confederate position. When the Federals were within easy range, Ewell’s men rose and fired a volley into the blue line, causing its center to break and fall back.

Lieutenant George Peck, 2nd Rhode Island Infantry, was "seeing the elephant" for the first time in this battle, having just joined the army. He wrote with exactness his recollections after crossing the creek. "We were at the foot of a moderately steep, turf-covered declivity over whose summit the foliage of dense trees was visible. Some twenty rods to our left this growth, sufficiently dark and threatening, extended down the hillside to the creek....At the word 'FORWARD!' the men sprang to their feet, fired into the woods, and with a cheer dashed forward on the run. Gaining a few rods, they fell, loaded (officers meanwhile simply stooping), rose again, fired, and made a second dash....With the third dash came the words: 'Now close on them--Go for them!"

As Lieutenant Peck's company continued "at length I imagined I had about reached the summit, and must be ready to close on the hostiles, so I looked up; but lo! no one was before me. Surprised and perplexed, I turned to the left and no one was there. The colors were already half way down the hill and moving deliberately to the rear; the soldiers on the extreme left had already reached the creek. Glancing now to the right, I found the nearest man, eight or ten feet away, was wheeling about. As I did not care to present any Confederate with either sword, watch or revolver, and could offer but slight resistance when single-handed, I concluded to retrace my steps also, and accordingly commenced a march in common time to the rear."

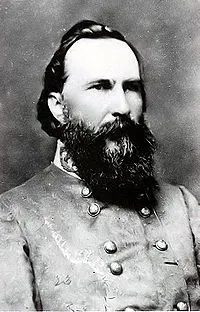

What happened then as Peck's regiment and others retreated to the creek, portions of General Custis Lee's command, caught up in the spirit of the moment, made a counterattack all the way to the creek, only to be thrown back themselves with great loss. Of particular note among their casualties was Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield, former Chief of Artillery in Jackson's Corps . Regrouping themselves, the Federals once again charged Ewell’s line, this time overwhelming it on both flanks but only after deadly hand-to-hand combat. Their efforts would result in the capture of six Confederate generals (Ewell, Custis Lee, Joseph Kershaw, Seth Barton, James Simms, Dudley Dubose) and more than 3,000 men as prisoners.

Farther to the south, Merritt’s cavalry prepared for their mounted attack. Some of the troopers, having lost their mounts during the campaign, had acquired mules to ride in their stead. One rider remembered "it took my mule just about four jumps to show he could outclass all others. He laid back his ears and frisked over [the] logs and flattened out like a jackrabbit....He switched his tail and sailed right over among the rebs, landing near a rebel color-bearer of the 12th Virginia Infantry...the color-bearer was a big brawny chap and he put up a game fight, but that mule had some new side and posterior uppercuts that put the reb out of the game."

Soon though the cavalrymen likewise overcame the Southerner's stubborn resistance and captured two more generals (Eppa Hunton and Montgomery Corse), although many of Anderson’s men managed to escape through the woods. As these refugees fled the battlefield and headed west toward Rice’s Depot, they had to scramble through the valley of Big Sailor’s Creek. General Lee had ridden to a knoll overlooking this creek and seeing this disorganized mob, exclaimed: “My God! Has the army been dissolved?”

What is collectively referred to as the Battle of Sailor’s Creek was actually three separate engagements. The fight at the Hillsman farm between Wright and Ewell, Merritt versus Anderson at the crossroads, and a third at Lockett’s farm two miles north from the first two. When the wagon train Gordon followed became bogged down at the double bridge crossing over the confluence of Big and Little Sailor’s Creek, his men were forced to protect them. Making a stand on the high ground around Lockett’s, the Confederates awaited the arrival of Humphrey’s II Corps just before dusk. The fighting became intense as the battlelines came together around the farmhouse. A Northern infantryman recalled "we advanced to a White House [Locketts] on Sayler's Creek, where we had an engagement and I found some protection behind the house. I called Sergt. Percival's attention to what I thought a better position near the hen coop, fifteen feet distance, but he ordered me to remain where I was. I thought I could get better aim from the other position. I had been hit just before reaching the house and wounded slightly. We had notified the occupants of the house to adjourn to the cellar; bullets came pattering against it" (The house still stands with evidence of the fighting visible). As the sound of fighting echoed from the south, the Federal infantry gradually pushed the Southerners back into the low ground along the creek. Using the wagons themselves as barricades, Gordon’s men fought desperately. Only when a Federal flanking column was seen crossing further to the north at Perkinson’s sawmill, did the Confederates retreat up the opposite slope. Nightfall brought an end to the fighting with the spoils being 1,700 prisoners and over 200 wagons for Humphreys’ men.

It would once again be another night march for veterans of the Army of Northern Virginia. The remainder of Gordon’s Corps would trudge on to High Bridge, crossing the Appomattox as they headed down the railroad for Farmville. Those remnants that escaped disaster at the other two fights were placed in command of Major General William Mahone who likewise crossed on the gigantic railroad bridge. Lee followed Longstreet’s troops and Fitz Lee’s cavalry along the road running south of the river into the town, arriving there in the early morning hours of the 7th. At this point they would find the long awaited subsistence, several train loads containing over 80,000 rations of meal and 40,000 of bread to be exact. Not long after his men began receiving their allowance and started preparing their meals, the popping of carbine fire was heard to the east: Federal cavalry were approaching the outskirts of town. The Confederates quickly closed up the boxcars and sent the trains westward down the rail line to Pamplin’s Depot. They would have to get their rations elsewhere and at another time, the most likely place being Appomattox Station thirty miles away. By 1:30 p. m., the Federals had gained control of Farmville as Lee’s army retreated to the north side of the Appomattox.

The Battles Of High Bridge and Cumberland Church

April 7, 1865

Farmville was a tobacco town of some 1,500 inhabitants in 1865, serving the Confederacy in numerous ways during its’ four years of existence. Nestled on the south bank of the Appomattox River, a wagon works was located here as was a Confederate General Hospital, boasting 1200 beds. Built principally for sick soldiers rather than battle casualties, with fighting now coming to the area for the first time in the war, it would soon be put to use by both sides. The South Side Railroad, in coming into Farmville from the east, followed a somewhat curious pathway. From Rice’s Station, about six miles away, the line crossed to the north bank of the river over High Bridge, then curved to the southwest, recrossing the Appomattox into the town. From that point west, it stayed south of the river to Lynchburg. The main reason for this seemingly out of the way route is that Farmville itself is in low bottom with a steep high grade to the east. Locomotives leaving the town and heading in that direction needed a gradual rise to do so, and this was only provided by this circuitous route. Consequently, there were two railroad bridges over the generally unfordable Appomattox in the vicinity of Farmville along with two wagon bridges that adjoined them. Lee figured that if he could get his men across then burn all four bridges behind them, the pursuing Federal forces would be stalled for some time while they waited for their pontoon bridges to arrive. In the meantime, he could use the respite to gain some distance between the armies. There was only one problem with this idea, and that was pointed out by one of his subordinates, General E.P. Alexander. Since the army was now heading west to Appomattox Station, by following the road north of the river, it was about 38 miles to that point. If they had stayed south and followed generally the rail line, it was only about 30. In other words, the shorter distance would be left open to the enemy.

As Sheridan’s cavalry (Crook’s Division) poured into Farmville from the eastern heights, the last of Lee’s troops crossed the covered wagon and railroads bridges, both of which were put to the torch. Confederate artillery peppered the blue troopers in the town from Cumberland Heights on the north side of the river, while the infantry would march forward to the sound of gunfire up ahead. What could it be? The enemy couldn't have crossed the Appomattox at High Bridge to the northeast could they? Lee soon found his orders had not been completely carried out and his worst fears were now realized. Although somewhat delayed, the High Bridge had been fired successfully with a section of it being destroyed, but the lower wagon bridge, fired too late, was quickly extinguished by Federal skirmishers allowing the following II Corps to cross. To take care of this unanticipated threat, General Mahone brought his forces to the high ground around Cumberland Church and began entrenching in a defensive position, covering the route of retreat Lee’s column would take.

Cumberland Church is located about five miles northwest of High Bridge and four north of Farmville. Describe as a “rural Virginia church, painted, but without a steeple and rudely finished,” the Confederates dug in with their breastworks laid out in somewhat of a fish-hook shaped line, facing toward the north and east. About 2 p. m., lead elements of Humphreys’ Corps arrived on the scene although with only two of the three divisions (First and Third). The Second Division, under General Francis Barlow, had followed Gordon’s column down the railroad toward Farmville before breaking off the moment just north of the river. In the skirmishing that took place along the way, General Thomas Smyth would be mortally wounded by a sniper’s bullet and he would become the last Federal general officer killed in the Virginia fighting.

General Nelson Miles’ First Division initially came in contact with Mahone’s Division, which was supported by artillery from Colonel William T. Poague’s command. A quick rush on Poague’s position by Federal skirmishers allowed them to capture a few of these guns, although they were quickly retaken by Southern infantry support troops. After realizing the large force in his front, Humphreys set about maneuvering his divisions into place with Miles facing to the south, and General Regis de Trobriand to the west. Seeing that the Confederate defensive position was protecting Lee’s wagon train and his route of withdrawal, it was determined that Miles would make an attack on Mahone’s left flank and attempt to turn it. Humphreys also felt that the VI Corps, which should now be in Farmville, would have crossed the river and be attacking Lee in his rear. Hearing firing in that direction, Miles sent one brigade, Colonel George Scott’s, charging across a rolling terrain broken by numerous ravines, which managed to get around and in rear of Mahone’s flank. Mahone quickly brought up reinforcements, probably from General “Tige” Anderson’s Brigade, who cut them off and scattered the group. One Union regiment, the 5th New Hampshire, lost not only its colors but 57 men captured in the action. Nightfall brought an end to the fighting.

Back in Farmville, the town was alive with Federal troops, but few were across on the north side of the river. In fact, only one division of cavalry, General Crook’s, was actually able to ford the river and menace Lee’s troops that afternoon. Riding into the retreating Southern wagon train about 4:00 p. m., the leading brigade under General J. Irwin Gregg made an attack on it. Nearby Southern horsemen would counter, and send the blue troopers scurrying back to Farmville, minus their commander, General Gregg, who was captured. It was this fighting that Humphreys probably heard and thought was the VI Corps assaulting Lee’s rear. Until a pontoon bridge could be built at Farmville, the Federals had to cross either the wreckage of the burnt bridges or ford as best as possible. General Ord’s Army of the James lent their pontoon bridge to the VI Corps, while they themselves stayed south of the river in the town.

The situation then, on the night of the 7th, was this. Grant would have one corps, the II, on the north side of the river with Lee; the VI would soon be over. In Farmville were Ord’s troops composed of the XXIV Corps and a division of the XXV Corps. Crook’s Division would return to Farmville then ride westward to Prospect Station on the railroad. The rest of the Sheridan’s cavalry was about seven miles to the southwest near Buffalo River. The V Corps, General Charles Griffin’s, were six miles south of Farmville at Prince Edward Court House. By early the next morning, they and Sheridan would reach the South Side Railroad at Prospect Station, to be joined by Ord and Crook. This entire command would then follow the shorter route to Appomattox Station. Depending upon which point they camped at on the night of the 7th, the men would have to march between 30 and 38 miles to get in front of Lee’s army. The 8th was going to be the day that could finally put an end to the campaign.

With nightfall ending the fighting at Cumberland Church, Lee realized that once again he must ask his men to make a night march to elude the Federals. Under the cover of darkness, his two columns continued their march toward Curdsville, New Store, Appomattox Court House, then Appomattox Station. Before leaving the area, the commanding general would receive a note through the lines from General Grant, now in his Farmville headquarters. In it Grant brought up the possibility of surrender for the Confederate army. Looking it over, Lee handed it to General Longstreet, who read it and replied, “not yet.” More bloodshed was yet to come.