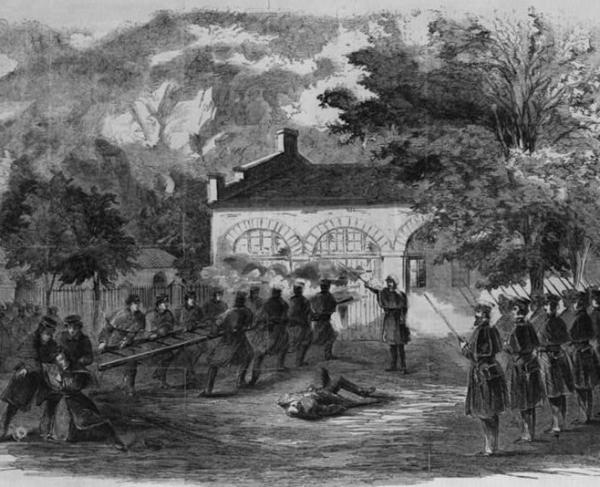

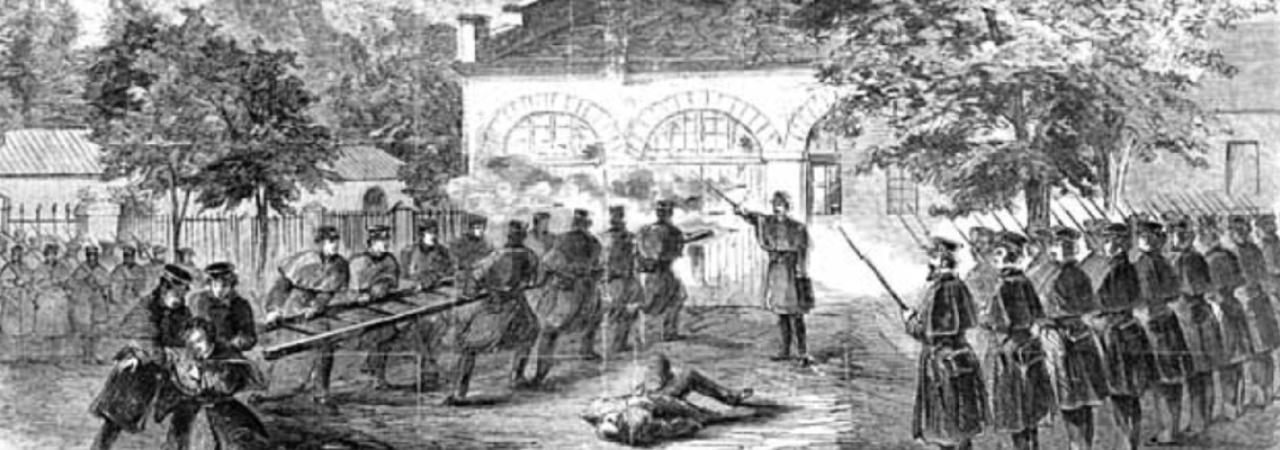

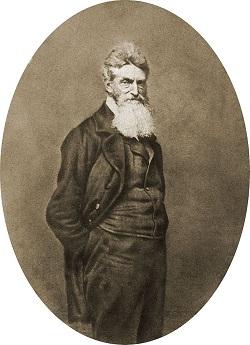

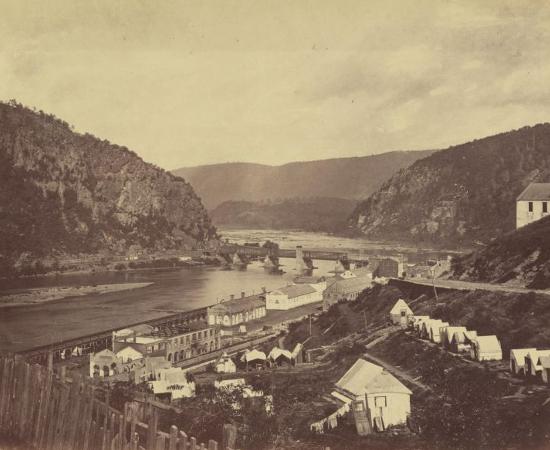

When the abolitionist John Brown seized the largest Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October of 1859, he forced the citizens of the United States to reconsider the immorality of the institution of slavery and the injustices enforced by the government. The raid on Harpers Ferry and the resulting execution of Brown was a major turning point in the American abolitionist movement, causing many peaceful abolitionists to accept more militant measures to push for the end of slavery. The legitimization of slavery by the state and societal violence, such as the “Bleeding Kansas” conflict, plagued a nation rapidly approaching civil war, and during the 1850s, the U.S. faced extreme sectional tension as slave-holding and free states struggled to maintain a balance of power in a divided government. Brown’s actions were a reflection of the violence of his time and a reaction to what he viewed as the legalized criminality of slavery upheld by the state under which he lived. Brown’s actions in Virginia and at the battle of Osawatomie, Kansas, were applauded by the antislavery populace, and New England abolitionists and intellectuals, such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, unaware of the bloody details of Brown’s operations at the Pottawatomie Massacre in Kansas, helped to establish the image of Brown as a martyr in the North. Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson championed John Brown’s sacrifice while overlooking the violent aspects of Brown’s character, in order to promote him as a heroic symbol for the abolitionist cause. As a result of this judgment by New England intellectuals and the ensuing martyrdom of Brown in the North, many Southerners viewed the raid as a larger Northern scheme to directly attack the South, leading to increased sectional distrust and accelerating the approach of secession in 1861.

The secession of the Southern states and the firing on Ft. Sumter on April 12, 1861, ended a long period of unsuccessful compromises that failed to maintain national unity. During the first half of the nineteenth century, the young nation struggled to preserve a political equilibrium between slave and free states as new territories in the west began to enter into statehood. In 1820 the federal government issued the Missouri Compromise to establish a balance between incoming slave and free states. Although half of the U.S. was composed of slave-holding states, Northern free states benefited from the institution of slavery. Major cities, such as New York City and Boston, grew rich from the textile industry, which heavily depended on the supply of cotton picked by American slaves. Ironically, the slavery-dependent textile industry increased the wealth of the city of Boston during the 1800s, allowing it to become a center of American art and culture, from which the abolitionist movement would emerge. Abolitionists demanded the emancipation of slaves in Washington DC and many began to demand the immediate abolition of slavery in the U.S., protesting the government’s legitimization of the slavery system. An increased number of antislavery petitions were sent to Congress but were blocked from consideration by the effect of the Gag Rule in the House of Representatives that had been put into place in 1836. To assuage the growing political tension between slaveholders and Free-Soilers, the federal government enacted the Compromise of 1850, which included the controversial Fugitive Slave Act, requiring free state officials to return runaway slaves to their masters, and in 1854 Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, allowing local citizens to decide whether slavery should be allowed in the Kansas and Nebraska territories through Popular Sovereignty. The U.S. government, constricted by the contrasting interests between slaveholders, Free-Soilers, and the more radical demands of the increasingly popular abolitionists, began to face extreme sectional disharmony, which was reflected in the escalation of violence in American society.

John Brown’s experiences in the first half of the nineteenth century would solidify his lifelong hatred of slavery into a more passionate commitment to combat the slave system and the government that upheld it. John Brown was born in 1800 and lived through a period in which there was suppression of antislavery ideas by the state, increased violence against abolitionists, and a number of slave revolts. Brown was influenced by Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, the bloodiest slave revolt of its time, which resulted in the deaths of more than fifty Virginian slaveholders. Although it was repressed, it had instilled fear into the citizens of slave states and threatened the plantation way of life. During the 1830s, anti-abolition riots took place in Northern cities, such as New York and Philadelphia, and Northern abolitionist printing press owners faced great risks from proslavery mobs. William Lloyd Garrison, one of the most well-known leaders of the abolition movement and the editor of the Boston newspaper The Liberator, barely avoided being lynched by an anti-abolitionist mob. However, it was not until the murder of the abolitionist newspaper writer Elijah Lovejoy that Brown truly devoted himself to fighting slavery. Reverend Edward Brown recalled his cousin John Brown’s words at a church meeting after the Lovejoy incident: “Here before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.”

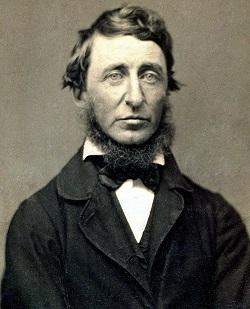

While most abolitionists were in favor of using peaceful ways to push for emancipation, Brown believed that militant action had become the only effective way to abolish slavery. Previous peaceful measures had failed to persuade the government to emancipate the slaves or to even enforce the restrictions that were already placed on the slave system. Garrison supported the use of moral and social reform and called for the extension of citizenship rights to African Americans. Frederick Douglass, the most influential black abolitionist, favored direct political reform. Henry David Thoreau placed value on the responsibility of the individual to defy laws that opposed one’s moral principles and to not participate in a government that upheld unjust institutions such as slavery. Unlike these New England-based abolitionists, Brown began to view violence as the last resort in the face of the growing intransigence of Southern slaveholders and increased injustices performed by the state: the Supreme Court Ruling in Dred Scott v. Sanford and the lack of government enforcement on the ban of the Atlantic slave trade (the last slave ship to arrive in the U.S. would do so in 1859). Only after Brown’s trial for his actions at Harpers Ferry did the abolitionist movement increase in popularity in the North. After Brown’s raid, many formerly pacifist abolitionists became willing to contemplate violent means for achieving emancipation. His militant abolitionist views were fueled by violence and oppression in American society and the injustices of the state, causing him to become a major turning point in the ideology of the abolitionist movement which had been previously based in nonviolence.

During the Bleeding Kansas conflict in the 1850s, Brown and his followers fought against proslavery “Border Ruffians,” gaining admiration from New England abolitionist elites and intellectuals. News of Brown’s defense against proslavery forces at the battles of Black Jack and Osawatomie was praised by New England abolitionists, and when Brown returned to New England from his exploits in Kansas, his friendship with Franklin Sanborn, a well-connected New England abolitionist, propelled him into the sphere of well-known Boston antislavery intellectuals, such as Emerson and Thoreau. When Sanborn introduced Brown to the Transcendentalists in Concord, Emerson’s and Thoreau’s admiration of Brown truly began to flourish as they saw Brown through the frame of view that Sanborn had developed for him. However, in New England abolitionist circles Brown rarely spoke of the Pottawatomie Massacre in Kansas, in which he had retaliated against the Border Ruffians by hacking to death five proslavery civilians with broadswords in the middle of the night. Although the murdered men were associated with proslavery groups in Kansas, at least three out of the five had not even owned slaves. The historian Tony Horwitz describes the bloody impact of the 1856 Pottawatomie Massacre: “Now, in a single strike, Brown had almost doubled the body count and inflamed his already rabid foes, who needed little spur to violence. Not for the last time, Brown acted as an accelerant, igniting a much broader and bloodier conflict than had flared before…If it was Brown’s intent to bring on a full-fledge conflict, he got his wish. The number of killings escalated dramatically in the months that followed, earning the territory the nickname ‘Bleeding Kansas.’” Nevertheless, Emerson and Thoreau had developed a positive perception of Brown through the help of Sanborn and the slowness and imprecision of the transfer of news during the time in which they lived. This positive view of Brown by New England intellectuals would be fundamental for the creation of Brown’s image as a martyr in the North after his execution.

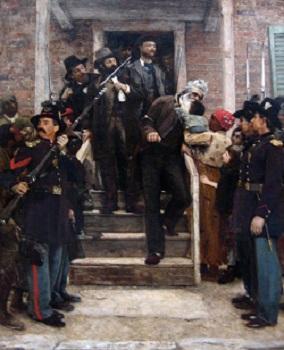

When the news reached the North that Brown and twenty-one of his followers had seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry on the night of October 16, 1859 in an attempt to instigate an armed slave uprising in Virginia, many Boston intellectuals and abolitionists rose to defend the man who had used violence to threaten the institution of slavery. However, most Northerners initially thought Brown had acted from insanity. The Chicago newspaper The Press and Tribune characterized Brown as an “insane old man” and a “monomaniac who believes himself to be a God-appointed agent to set the enslaved free.” Another newspaper in Cincinnati, Ohio, The Enquirer, stated that “the time will come when the transaction will be permitted to appear as it really is: and then, perhaps, we shall be able, without, bias, not only to measure the character of old Brown but to get a true estimate of those exceedingly shallow and foolishly mischievous men who are professing to discover the late Harpers Ferry abortion a great event in the progress of abolition.” Widespread Northern support for Brown was not immediate. While Brown was waiting in prison to be hanged for treason against the state of Virginia, Henry David Thoreau wrote a speech called “A Plea for Captain John Brown,” which he delivered to the citizens of Concord, Massachusetts. During a time of intense political turmoil, Thoreau sought to defend Brown’s ideals and image, not to save him from execution: “I am here to plead his cause with you. I plead not for his life, but for his character,--his immortal life.” Thoreau was not necessarily defending Brown’s use of violence, but rather the ideals for which Brown sacrificed his life. Thoreau viewed Brown as a hero and as a “man of rare common sense and directness of speech, as of action; a transcendentalist above all, a man of ideas and principles.” The fact that Thoreau, a leader of the American transcendentalism movement, characterized Brown as a “transcendentalist above all” truly showed Thoreau’s admiration for Brown’s sense of moral obligation and sacrifice of life to challenge the inequality and criminality legitimized by the state. Transcendentalism places value on the purity and self-determination of the individual in the face of a corrupt society that supports immoral institutions. Thoreau saw Brown as a fellow transcendentalist because he stood up against the institution of slavery. In “A Plea for John Brown,” Thoreau described only the positive qualities of Brown’s character in order to appeal to his audience’s emotions and sense of patriotism:

He was a superior man. He did not value his bodily life in comparison with ideal things. He did not recognize unjust human laws, but resisted them as he was bid. For once we are lifted out of the trivialness and dust of politics into the region of truth and manhood. No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature, knowing himself for a man, and the equal of any and all governments. In that sense he was the most American of us all. He needed no babbling lawyer, making false issues, to defend him. He was more than a match for all the judges that American voters, or office-holders of whatever grade, can create. He could not have been tried by a jury of his peers, because his peers did not exist.

The language Thoreau used to describe Brown emphasized the Transcendentalist traits Thoreau saw in his character. Thoreau stated that Brown challenged “unjust human laws” and sacrificed his life for a higher law, implying that Brown valued the “dignity of human nature” over the dignity of human life. Thoreau understood that the loss of human life was sometimes necessary to achieve a more ideal state, and, as a result, Thoreau indirectly excused Brown’s violence. When Thoreau portrayed Brown as a unique and heroic individual whose “peers did not exist,” he essentially was defining the significance of the transcendentalist individual in a corrupt society. However, Thoreau viewed Brown through a distorted lens and either was unaware or deliberately overlooked the full extent of Brown’s violence in Kansas.

This view of Brown’s character was shared by Ralph Waldo Emerson, another major leader of the American transcendentalist movement. A month after Brown’s execution, Emerson gave a speech in which he tried to persuade his audience of the virtue, religiousness, and courage of Brown in an attempt to disprove the accusations of Brown’s evils and savagery: “He grew up a religious and manly person, in severe poverty; a fair specimen of the best stock of New England; having that force of thought and that sense of right which are the warp and woof of greatness…Thus was formed a romantic character absolutely without any vulgar traits; living to ideal ends, without any mixture of self-indulgence or compromise…” By avoiding the issue of his brutality in Kansas, Thoreau, Emerson, and others were able to create a heroic and virtuous image of Brown, helping to establish him as a martyr in the North.

Because Brown had well known intellectual supporters in New England, many Northerners began to view Brown as a martyr instead of as a fanatic. In the article “John Brown’s Body,” historian Gary Alan Fine asserts that “cultural elites" in Boston were "in position to define and defend Brown’s reputation” and that during the mid-1800s they were “recognized as the dominant force in American arts and letters, a point that was widely acknowledged.” If Brown’s supporters had not placed him onto the moral high ground or had not built him up to be a brave man who had acted on higher principles, then their fellow Northerners would most likely have dismissed Brown as an insane fanatic, and the historical symbolism of Brown may have been extremely different. After Brown’s execution, these “cultural elites,” including Thoreau and Emerson, wielded power to establish Brown as a symbol of freedom despite their lack of information of his full character, causing many Northerners to see Brown in a more positive light, which further divided the people in the North and the South.

Although Thoreau, Emerson, and other supporters of Brown sought to persuade their fellow Northerners to take Brown seriously, most powerful slave-holding Southerners did not need to be told that Brown was a serious threat to their way of life. Many Southerners did not understand how a man who had murdered their people and threatened their entire way of life could be made a martyr and hero in the North. On the other hand, some Southerners gladly seized on the incident at Harpers Ferry as a way to energize and motivate the South to secede from the Union. Edmund Ruffin, a Virginian fire-eater and pro-slavery radical, wrote that Brown could “stir the sluggish blood of the South” into secession. The historian Karen Whitman also describes how the raid allowed the South to justify secession from the Union: “Brown forced the South to retreat from any further accommodation with the North. He offered Southern secessionists an argument and a warning. The argument was used by the South to hasten secession: the raid symbolized the ruthlessness of the North, of abolitionism, in attacking the cherished institutions of the South.” The trial and execution of Brown pushed the nation closer to civil war.

Bibliography

Secondary Sources:

Fine, Gary Alan. “John Brown’s Body: Elites, Heroic Embodiment, and the Legitimation of Political Violence.” Social Problems 46, no. 2 (May, 1999): 225-249.

Horwitz, Tony. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2011.

Meinke, Scott R. “Slavery, Partisanship, and Procedure in the U. S. House: The Gag Rule, 1836-1845.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 32, no. 1 (February 2007): 33-57.

Prince, Carl E. “The Great ‘Riot Year’: Jacksonian Democracy and Patterns of Violence in 1834.” Journal of the Early Republic 5, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 1-19.

Ruchames, Louis. “His Life in Brief.” In A John Brown Reader, 16-32. New York: Abelard-Shuman, 1959.

Turner, Jack. “Performing Conscience: Thoreau, Political Action, and the Plea for John Brown.” Political Theory 33, no. 4 (August 2005): 448-71.

Whitman, Karen. “Re-evaluating John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry.” West Virginia Archives and History 34, no. 1 (October 1972): 46-84.

Primary Sources:

Brown, Edward. “In the Words of Those Who Knew Him.” In A John Brown Reader, edited by Louis Ruchames, 179-81. New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1959.

The Clotilda: A Finding Aid. Accessed April 22, 2014. http://www.archives.gov/atlanta/finding-aids/clotilda.pdf.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “John Brown.” Speech presented in Tremont Temple in Boston, January 6, 1860. In A John Brown Reader, edited by Louis Ruchames, 296-99. New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1959.

Enquirer (Cincinnati). “An Insurrection Without Negroes.” December 4, 1859.

Press and Tribune (Chicago). “Where the Responsibility Belongs.” October 20, 1959.

Thoreau, Henry David. “A Plea for John Brown.” Speech presented in Concord, MA, October 30, 1859. In Walden and Other Writings, edited by Brooks Atkinson, 717-43. Modern Library Paperback ed. New York: Random House Inc., 2000.