Through the Eyes of the British

“Our non-emancipated soldiers are almost irresistibly tempted to desert to our foes, who never fail to employ them against us,” wrote an anonymous Patriot in Philadelphia in 1777. He was referring to the small number of enslaved men who had signed on to fight in the Continental Army. Most of them did so because they had no choice: their masters forced them to to take their spot in the army. However, this individual’s concerns focused on the glaring temptation that many enslaved Africans and Black Americans faced as the British Army had promised any slave their freedom in trade for their service in His Majesty’s army. For some Americans, the prospect of armed slaves fighting against the American Cause was terrifying.

From the start of American Revolution, many in Great Britain favored arming slaves with British weapons and resources; the hope being it would deprive the Southern states of workers, create an insurrection, and bring the American economy to a halt. Lord Dunmore, serving as Royal Governor of Virginia in 1775, issued a proclamation declaring that any slave who escaped and joined the British Army would earn their freedom. Soon, Dunmore had a fighting force of nearly 800 soldiers. After several battles, Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment was decimated by smallpox and disbanded.

The British also encouraged slaves to run away because they wanted to remove skilled slaves from American hands. Enslaved people were often trained and very talented in carpentry, masonry, as blacksmiths, shoemakers, seamstresses, bakers, and distillers. Many slaves in Maryland and Virginia used their knowledge of the tidal regions of the Chesapeake Bay to evade capture from their masters. Others, such as a free man named Jerry, were arrested for giving weapons to escaped slaves in support of the British. When South Carolina Royal Governor William Campbell protested his death sentence, an angry mob threatened to hang Jerry on his front doorstep. A man named Tye became a raider for New Jersey Loyalists around Monmouth, employing about 25 men of all nationalities. Tye’s Black Brigade was very successful until being gunned down by Captain Joshua Huddy, who defended his house from being plundered. Huddy single-handedly put down the raiders and kept his house.

Not all enslaved people took the British at their word. While it was generally believed within circles of enslaved people that the British offered the better opportunity of freedom from bondage, others refused to leave their plantations. Some stayed behind even after their masters had left, and refused to leave when British forces descended upon the vacant properties. Many recognized that Loyalist citizens owned slaves too. British officers were also known to acquire captured slaves for themselves. Even still, tens of thousands of enslaved people escaped their masters and crossed the British lines. Seldom few would actually see action in the British army.

The majority of African slaves who fled to the British were given non-military jobs with the army. These were usually manual labor positions that saw breastworks built and trenches dug. Indeed, the work experience that enslaved individuals brought with them proved formidable for British commanders who found useful methods of employing them. While a majority of the men were put to manual labor, others were given military training and armed with muskets. In 1779, the southern British army armed 200 slaves to defend Savannah, Georgia. Other former slaves in British uniforms fought in Virginia in 1781. A slave named Billy was convicted of treason by a Virginia court for attacking civilians from a British ship. His master, a lawyer, successfully overturned his death sentence by arguing that, as a slave, he could not be legally tried because he was not recognized as a citizen with rights. Despite this rare case, the effect of arming former slaves was immediate. American slave-owning communities “ran their slaves” by moving them regularly out of reach of British scouting parties. Many escaped slaves who were captured by their masters were punished by being sold at auction. In some cases, this actually proved to be a blessing. These very few were immediately freed by their purchaser.

As the British army became trapped at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781, many enslaved people with the British had come down with smallpox. In one of his last decisions as commander, British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis ordered all infected persons to return to their plantations. He hoped the disease would spread among the healthy population and devastate the countryside. His plan failed, and the British fell at Yorktown in October, essentially ending the British Army’s war against American Independence. As the peace treaty was being hammered out overseas in 1782, British commander Guy Carleton was being hounded by American farmers and masters who demanded the British hand over their property. Several state assemblies conveyed the help of Gen. Washington to persuade Carleton to comply. Washington and Carleton held a meeting, but the British refused to recognize any escaped person who had crossed over prior to a ceasefire agreement in 1782 as property. The problem was tens of thousands of former slaves, thousands of whom were women and children, had escaped to the British lines, and more than enough had lied and assumed the identities of free people instead of slaves. In the end, the Americans did not get their escaped slaves back and over 50,000 former slaves left North America with the British army in 1783. For decades, the unresolved situation lead to fierce anti-British resentment in the South, who lost a disproportionate amount of their enslaved population. Of the 50,000, many settled in Nova Scotia and the Caribbean while others sailed back to West Africa and Great Britain.

Fighting for American Independence

“I served in the Revolution, in General Washington’s army...I have stood in battle, where balls, like hail, were flying all around me. The man standing next to me was shot by my side - his blood spouted upon my clothes, which I wore for weeks. My nearest blood, except that which runs in my veins, was shed for liberty. My only brother was shot dead instantly in the Revolution. Liberty is dear to my heart - I cannot endure the thought, that my countrymen should be slaves.” - Dr. Harris, a veteran of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, in an address to an anti-slavery society meeting in Francestown, New Hampshire, 1842.

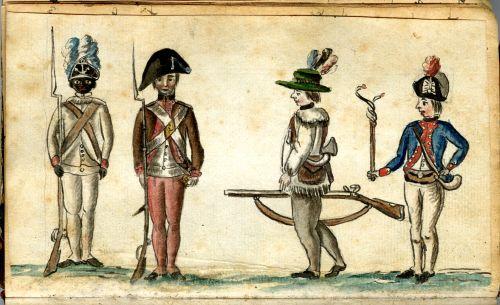

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment was an assembled unit in the Continental Army that has been documented as having a large and visible body of African-American soldiers within its ranks. Best remembered for their efforts to repel Hessian advancements during the Battle of Rhode Island in 1778, they were led by Maj. Gen. James Mitchell Varnum. Estimates indicate that between 120-140 soldiers out of 250 were Black. Though integrated like nearly all other Continental regiments, the 1st Rhode Island is remembered for employing slaves and freedmen before it was approved by Congress and Gen. Washington. Up until 1778, the Continental Army did not allow African-Americans to serve. Exceptions were made, however, to those who had served since the early days in Boston in 1775. These men were allowed. New recruits were not. Seeing this, Lord Dunmore issued his proclamation in 1775, enticing African-Americans, enslaved and free, to join the British. Washington did an about-face, but the states were still reluctant to arm African-Americans. This changed at the state level as 1778 saw huge shortages in enlistments from local townships. To fill their quotas, they began allowing enslaved people and free African-Americans to enlist. In return, slaves were promised their freedom for their service. By 1781, the Continental army was noted as being nearly one-forth African-American at Yorktown. Regiments were not segregated, and a German officer marveled at the professionalism and dress attire of America’s first Black soldiers.

Lemuel Haynes was born to a Black father and a white mother; he was indentured at five months of age to a white farmer who was also a Deacon. Haynes was raised as his son and was given an education. He eventually joined the Granville, Massachusetts militia in 1774 when he was 21 years old. He learned military tactics and was trained in Native American stealth-maneuvering. Haynes would write poems about his experiences during the war. He would later become the first Black ordained Congregational minister in the United States, and was a strong voice in the abolitionist movement. Some of his poetry consisted of the lines, “For Liberty, each Freeman strives; As it’s a Gift of God; And for it, willing yield their Lives,” (from The Battle of Lexington, 1775), and “I think it not [an exaggeration] to affirm, that even an African, has Equally as good a right to his Liberty in common with Englishmen...consequently, the practice of slave-keeping, which so much abounds in this land is illicit.” (from Liberty Further Extended, 1776).

Barzillai Lew served in the French and Indian War with his father. He married Dinah Bowman in 1768, a freedwoman from Lexington, Massachusetts who was a pianist. They would have several children who would all grow up to be musicians. Lew enlisted as a fifer/drummer in May 1775 in the 27th Massachusetts Regiment. He participated in the successful raid at Fort Ticonderoga in 1775 that brought the cannons back to Boston that drove the British out in 1776. He also fought at Bunker Hill in June 1775, playing the tune, “There’s Nothing Makes the British Run Like Yankee Doodle Dandy.” He was also witness to British Gen. John Burgoyne’s surrender to American forces at Saratoga, NY in 1777. The powder horn he carried throughout the war now sits in an African-American History museum in Chicago.

Peter Salem, a former slave, is credited with shooting and killing British Maj. John Pitcairn during the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775. Artist and soldier John Trumball painted the famous depiction of Bunker Hill, which he also participated in. Salem’s head can be seen in the top left corner beneath the three waving flags. Pitcairn can be seen to the right-of-center beneath the raised British flag, dying in his son’s arms. Salem had been in Concord, Massachusetts when the British marched to take the stockpiles of munitions there. Along with other American militia, Salem drove the British back to Boston. He would reenlist several times during the war, serving nearly five years before retiring to Massachusetts where he married and settled in Leicester. A monument stands there in his honor to this day.

Another brave American soldier, Salem Poor, was noted for his bravery during the events around Boston in 1775. Poor is credited with killing British Lt. Col. James Abercrombie, who is shown in Trumball’s painting, centered, laying flat on his back. Poor may or may not be the African-American depicted standing behind the white soldier with a drawn sword in the far right corner. For his efforts, Col. William Prescott petitioned to have him recognized for his services, “...we declare that a Negro man called Salem Poor of Col. Frye’s Regiment, Capt. Ames Company in the late Battle of Charleston, behaved like an experienced officer, as well as an excellent soldier, to set forth particulars of his conduct would be tedious. We would only beg leave to say in the person of this Negro centers a brave & gallant Soldier.” Poor would be with Washington at Valley Forge in 1778.

James Armistead Lafayette was a slave in Virginia owned by William Armistead. After gaining permission to join the war effort from his master, he came upon the British Army in Virginia in 1781 to gather intelligence for the turncoat, Benedict Arnold. In realty, Armistead was a double agent gathering intelligence for the Continental army under Maj. Gen. Lafayette. Armistead was very successful; his reports were vital to the planning of the Siege at Yorktown. He was so good at fooling the British that Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis is said to have been stunned at seeing Armistead standing next to Lafayette after the British surrender. Unable to secure his freedom because he had not technically served in the American army, William Armistead, along with the help of Lafayette, petitioned the Virginia assembly to free him. He was granted his freedom, and took Lafayette’s name as a thank you. In 1824, when Lafayette returned to the United States and toured Virginia, James Armistead Lafayette approached the tavern where the celebrated French general was receiving the cheers of the locals. Upon entering the tavern, Lafayette recognized him, embraced him and offered his thanks for his service. Armistead saluted the general one last time, and departed. Gen. Lafayette, a former slave owner turned abolitionist, once said, “I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery.”

James Forten is perhaps the most successful African-American in the early decades of the United States. Born free in Philadelphia, he was inspired as a boy when he heard the new Declaration of Independence read aloud in July 1776. Raised with a healthy work ethic and educated by abolitionist Quakers, Forten enlisted on an American privateer at age 14. Captured by the British, he evaded being sold into slavery by impressing the British captain with his skills and knowledge. He was instead treated as a prisoner of war and sent to the infamous prison ship HMS Jersey. 11,000 Americans died aboard the disease infested prison ships anchored in the New York Harbor during the war. Forten was paroled after seven months and joined a merchant ship where he spent years at sea. When he returned to Philadelphia, he took a job working for a shipping company owned by a family friend. Forten quickly learned how to make sails and riggings for tall ships. When the chance came to buy the company in 1798, Forten did so and revolutionized the industry. Soon, he became one of the wealthiest individuals in Philadelphia. Forten employed both Black and white workers and sought to improve the conditions of American society. He used his talents and influence to promote the abolitionist movement in the United States. Originally, he considered paying for free African-Americans to resettle in other countries, but he was convinced to change his position by Black Americans who considered the United States their home. He was a staunch opponent of the American Colonization Society, which sought ways to transport freed slaves and born-free African-Americans to colonize the new countries of Sierra Leone and Liberia. He befriended a young William Lloyd Garrison, a future firebrand in the abolitionist movement, and the two started the influential newspaper, The Liberator, which he contributed editorials to before his death in 1842.

Phillis Wheatley was born in Africa, and was kidnapped into slavery as a young girl. Purchased by John Wheatley of Boston in 1761 as a servant girl for his wife Susanna, Phillis showed her quick learning capabilities and was given an education by the Wheatley family. Phillis soon mastered Latin and Greek and was writing poetry by 1770. In 1773, she published Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Morale. It was the first publication of poetry by an African-American in the United States, and was recognized by the likes of John Hancock. Phillis wrote poems about George Washington taking command of the Continental Army in 1775. In return, Washington wrote her a letter thanking her, and invited the young woman to visit him at the army encampment in March 1776. It is unknown if she did. Having been freed following the deaths of John and Susanna Wheatley in the 1770s, Phillis married and struggled to earn a living for her family. Her writing work fell out of favor with the public during the war, and battling frail health, she passed away in 1784.

Further Reading

- African Americans Serving in the Armies of the Revolution (an online reading list)

- "The Black Pioneers and Others: The Military Role of Black Loyalists in the American War for Independence" By: Todd W. Braisted, in Moving On: Black Loyalists in the Afro-Atlantic World

- Dunmore's New World: The Extraordinary Life of a Royal Governor in Revolutionary America - with Jacobites, Counterfeiters, Land Schemes, Shipwrecks, Scalping, Indian Politics, Runaway Slaves, and Two Illegal Royal Weddings By: James Corbett Davis

- Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82 By: Elizabeth Fenn

- The Negro in the American Revolution By: Benjamin Quarles

- 'They Were Good Soldiers': African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783 By: John U. Rees