As the Revolutionary War’s first black-centered combat unit the short-lived Ethiopian Regiment merits attention. Like the segregated 1st Rhode Island Regiment (an integrated unit prior to February 1778, and integrated again as of July 1780) it was born of necessity and was centered around freed slaves. This monograph will examine the unit’s career, the events that led up to its formation, and the ripples of its existence even after disbandment.

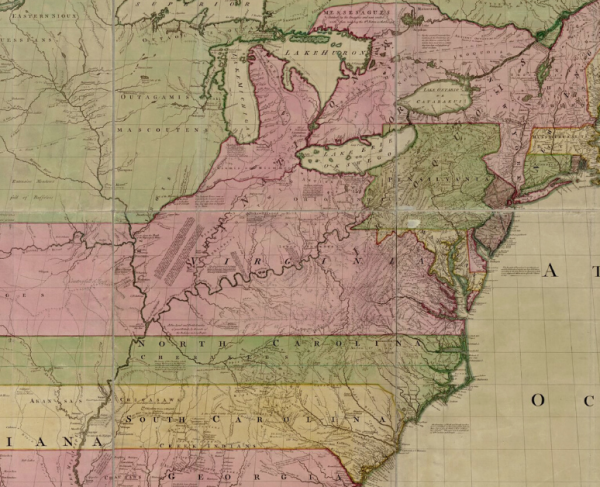

John Murray, fourth Earl of Dunmore, became Virginia’s reluctant Royal Governor in 1771. His career to that date had been relatively successful, from military service in the 1750s and 60s, through his 1770 appointment as governor of New York. In Virginia, his good fortune began to crumble. While his summer and autumn 1774 campaign against the Indians in western Virginia gained him some popularity, earlier that year he had dissolved the General Assembly after they passed a resolution supporting the people of the port of Boston, shut down and suffering under the Coercive Acts. To add to his troubles, members of the House of Burgesses reconvened as the First Virginia Convention, again pledged support for Boston, banned British trade, and elected delegates to the First Continental Congress.

Matters worsened the year following, when a Second Convention was convened. The members not only chose delegates for a Second Continental Congress, but Patrick Henry’s “Liberty, or … Death” speech, helped clinch the call for armed resistance. In April, with Virginians actively raising militia companies, Lord Dunmore decided to remove a large quantity of gunpowder from Williamsburg. After some difficulty, the stores were taken aboard the HMS Magdalen, but the confiscation only increased antipathy towards the governor. By early June Dunmore and his family had fled the capital for the safety of the armed ship Fowey in the York River. With that action, and despite any intention to do so, he permanently relinquished his governance of the colony.

Dunmore’s armed forces consisted of seamen and Marines from the few British warships in the area, plus a small number of loyal Virginians. In autumn, he was reinforced by the understrength British 14th Regiment (as of 23 October 1775, comprising about five companies, numbering 13 officers and 156 enlisted men). To remedy his predicament, more troops were needed, and the governor came up with a plan that would add to his little corps, simultaneously hitting the rebellious Virginians materially and financially.

During the Gunpowder Crisis, Dunmore threatened to "declare Freedom to the Slaves, and reduce the City of Williamsburg to Ashes.” In autumn 1775, he went one step further and created a corps of freed slaves, the Ethiopian Regiment. The British home government and others balked at instituting such measures. In October 1775, a group of “Gentlemen, Merchants and Traders” in Britain proclaimed their unwillingness to unleash the horrors of a slave rebellion on “our American brethren.” Lacking proper instructions British commanders in America proceeded on their own hook. Lieutenant General Thomas Gage took a hesitant lead. On 12 June 1775, he wrote William, 2nd Viscount Barrington, colonial secretary in London, “Things are now come to that crisis, that we must avail ourselves of every resource, even to raise the negroes, in our cause.” (Gage was likely prompted by Governor Dunmore, who two months earlier stated that if forced to react against rebellion, he could rely on “all the Slaves on the side of Government.”) South Carolina Royal governor Lord William Campbell advised Gage to not “fall a prey to the Negroes” and the Massachusetts military governor took no further action on that head.

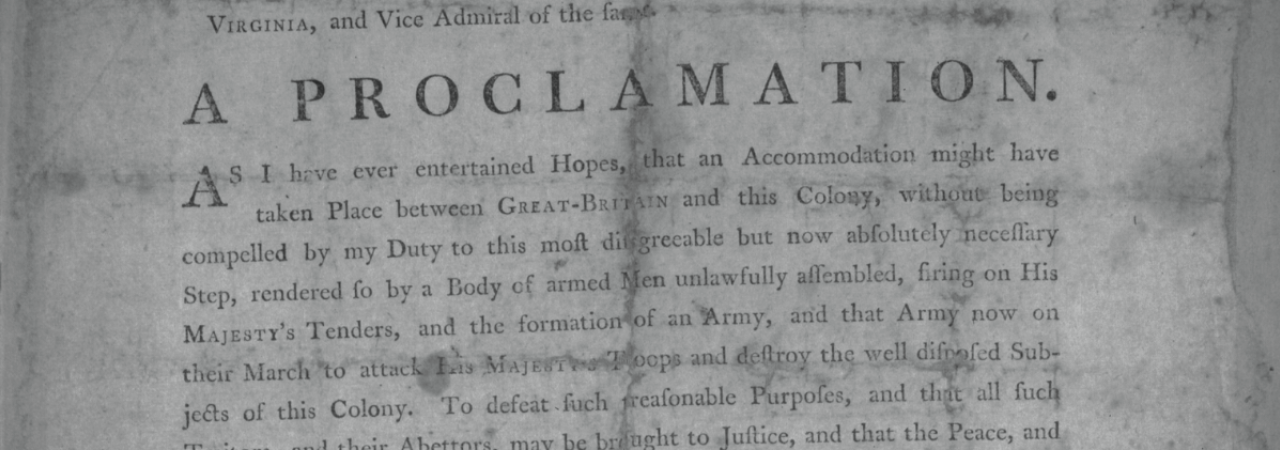

After quitting Williamsburg for shipboard accommodations in June 1775 Lord Dunmore soon added other vessels to his small fleet. This augmentation, along with a growing force of Loyalists and eventually the 14th Foot, enabled the governor to hit back at the rebels and gather recruits for the Ethiopian Regiment. One Virginian wrote that October, “Lord Dunmore sails up and down the river and where he finds a defenceless place, he lands, plunders the plantation and carries off the negroes.” These moves alarmed the insurgent Virginians, particularly when word spread and escaped slaves began placing themselves under the governor’s protection. An emboldened Governor Murray issued a 7 November 1775 proclamation, declaring martial law and announcing his intention to arm freed slaves: “I do hereby further declare all indented Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY’S Troops as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty …” On 30 November 1775 Lord Dunmore wrote Major General Sir William Howe, commander-in-chief in America, ‘you may observe by my proclamation that I offer freedom to the blacks of all Rebels that join me, in consequence of which there are between two and three hundred already come in, and those I form into Corps … giving them white officers and non commissioned officers in proportion …’. On 2 December the Virginia Gazette published the following: “Since Lord Dunmore’s proclamation made its appearance here, it is said he recruited his army, in the counties of Princess Anne and Norfolk, to the amount of about 2000 men, including his black regiment, which is thought to be a considerable part, with this inscription on their breasts:- ‘Liberty to Slaves.’” Along with the exaggerated estimate of Dunmore’s army, there is some question whether the use of that motto was true or a bit of Whig rabble-rousing; whatever the case, the phrase was extremely provocative.

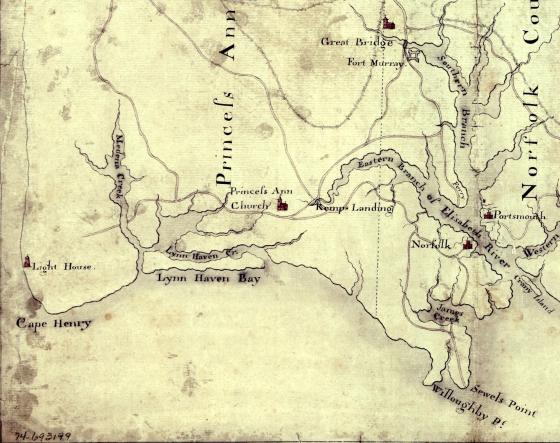

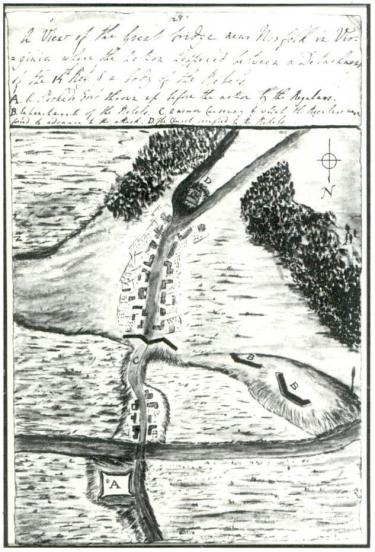

On 15 November 1775 Dunmore had gained a minor victory over local Whig forces at Kemp’s Landing, near Norfolk (during this action two black soldiers purportedly captured a Virginia officer). While some black troops participated in that affair, their first real combat was at Great Bridge where Crown and Whig forces had erected fortifications on opposite sides of a causeway. On 9 December Dunmore, in an effort to forestall a Rebel attack, sent his own forces against the opposing breastworks. The assault, led by the 14th Regiment, supported by contingents from the Queen’s Own Loyal Virginians and the Ethiopian Regiment, was a disastrous failure. While the Ethiopians saw little action at Great Bridge, among the casualties were two of Dunmore’s newly-freed slaves, now soldiers: wounded and taken prisoner were James Anderson, hit “in the Forearm – Bones shattered and flesh much torn,” and Casar, wounded “in the Thigh, by a Ball, and 5 shot – one lodged.” As a result of that defeat, Lord Dunmore’s troops were forced to abandon the mainland and return to their small fleet, occasionally occupying remote islands or isolated, defensible land in the area. (As a side note, William Flora, a free black Virginia militiaman, opposed the attack on the bridge, making this the first-known instance in this conflict of African Americans facing each other in battle.)

The following months were spent harassing and plundering waterside Whig properties, foraging for food, and other necessities. By late winter 1776, there was a new foe for Dunmore’s men to reckon with, variola major, otherwise known as smallpox. Compared to Europeans, North Americans were especially susceptible. Even more so were large southern slave populations, usually sequestered in the locale where they lived and worked, rarely traveling far afield. The men of the Ethiopian Regiment were hit hard, as were other former slaves who made their way to British protection. As the disease spread, Dunmore’s forces established an inoculation camp on Tucker’s Island, near Portsmouth. During that lengthy process they needed a more defensible position, so moved to Gwynn’s Island, in the Chesapeake Bay, at the end of May 1776. One British captain claimed most of the black soldiers had been inoculated while still at Norfolk and were felled by an unrelated fever, perhaps typhus, during the spring and summer. Several others noted that inoculations occurred on Gwynn’s Island. Whatever the case, the soldiers died in great numbers. In June Lord Dunmore wrote, “Had it not been for this horrid disorder I should have had two thousand blacks …” By the time the Royal governor abandoned Virginia, roughly 300 black men, women, and children sailed north with him. Approximately 150 were soldiers.

Reaching New York in late August 1776, the Ethiopian Regiment disembarked on Staten Island. The corps soon disbanded and its members dispersed. Some may have attached themselves to the “Company of Negroes,” a labor unit formed in Boston in 1775 and evacuated to Nova Scotia in March 1776. Others likely joined the Black Pioneers, the only black corps to be placed officially on the Loyalist establishment: with that recognition, the unit was allotted the same pay, clothing quality, provisions, and other necessaries, and served under the same discipline, as British troops. All other corps partly or wholly manned by African Americans and fighting for the Crown were privately organized or considered militia and did not serve under the same strictures or enjoy the benefits of the officially recognized Provincial Corps. The Black Pioneers were first formed in 1776, mostly with men from the Carolinas and a few from Georgia. The unit went north with Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton’s forces when they abandoned efforts to capture Charleston, South Carolina in late July. Unarmed, the Pioneers did menial work, from building fortifications and cleaning streets, to hauling wood, food, and other goods. They served in New York, Philadelphia (where they numbered 72 privates, 15 women, and 8 children), Rhode Island, and, later in the war, in Charleston. Many other African Americans labored as individuals or in small groups supporting the British war effort.

In the end, the Ethiopian Regiment served only one year, but its mere existence had far-reaching ramifications. First, it must be noted that Lord Dunmore’s notion of freeing enslaved men for military service had nothing to do with the abolition of slavery, but was a pragmatic act designed to strengthen his own small army and to hurt the rebelling Virginians; this is evidenced by the fact that the governor not only retained his own enslaved Africans, but allowed loyal Americans to do so as well. Despite any short-term benefit, Dunmore’s acts had a long-term deleterious effect. One historian notes, “His offer of freedom to slaves to fight against white Virginians and his recruitment of a regiment of black soldiers alienated most of the remaining influential planters and political leaders who until then had stayed loyal to the Crown.” And news of a Loyalist regiment formed of freed slaves soon reached the northern colonies. In 1775 some Whig commanders and politicians were having second thoughts about allowing African Americans, free or enslaved, to serve in the Continental Army; this despite the fact that numbers of black soldiers had fought during the 19 April Lexington and Concord operations, and again at Bunker Hill that June. By early 1776 the effort to deny black enlistment had failed and African Americans were (with only a few exceptions) accepted into Continental Army and militia service, a practice that continued to the war’s end. While not certainly known, this policy turnaround may have been at least partly due to the existence of the Ethiopian Regiment. Word that Crown military forces promised freedom for enslaved blacks spread quickly and far. In late September 1777, with Sir William Howe’s army about to capture the capital, Reverend Henry Muhlenberg took in “a nursemaid … with three English children of a prominent family which is fleeing from Philadelphia … There were also two Negroes, servants of the English family. They secretly wished that the British army might win, for then all Negro slaves will gain their freedom.”

A glaring dichotomy regarding black soldiers existed between Crown and Whig military forces. Despite the early enlistment of African Americans, in 1777 Major General Howe barred them from serving in Loyalist units on the Crown establishment. British army orders, New York, 16 March 1777:

The Commander in Chief being desirous that the Provincial Forces should be put on the most respectable Footing, and according to his first Intention be composed of His Majesty’s Loyal American Subjects, has directed that all Negroes, Mollattoes, and other Improper Persons who have been admitted into these Corps be immediately discharged. The Inspector Genl. of Provincial Corps will receive particular Orders on this Subject to Prevent such Abuses in Future.

By comparison, Continental Army and Whigs states’ militia were, with very few exceptions, integrated the entire war.

African Americans continued to serve as armed soldiers in Loyalist units after March 1777, but those were mostly militia or irregular corps. Perhaps the best known was a band of “refugees” commanded by “Colonel Tye.” Titus, or Tye, is known to have run away from his Shrewsbury, New Jersey master in November 1775, reputedly going on to serve in the Ethiopian Regiment. He later led a group of black and white Loyalists operating from the fortified Sandy Hook lighthouse. Tye and his men (known colloquially as the “Black Brigade”) harassed local Whigs from early 1779 until his death from wounds in autumn 1780. Tye’s “Brigade” disintegrated after his death. but Loyalist African American partisans, with their white counterparts, continued to operate along the New Jersey coast well into 1782.

Afterword: Smallpox remained a problem for the remainder of the war, particularly for blacks who left bondage behind to take their chances with the King’s forces. Historian Gary Sellick argues that the fact and danger of smallpox affected British military policy towards harboring African Americans as the war progressed. Lord Dunmore armed and inoculated ex-slaves in 1775 and 1776, but from 1777 onwards blacks under British protection, especially in the south, were not immunized. Instead, once infected with smallpox they were left without care and either quarantined or expelled from the lines. From Virginia to South Carolina hundreds, if not thousands, of formerly enslaved African Americans suffered and died as a result of this policy. One reason for this neglect was the 1777 British decision to not accept the service of armed blacks in the Loyalist military establishment. Without any military purpose, armed or otherwise, black men and their families were largely neglected. By contrast, African Americans in Continental service were inoculated along with their white comrades when a large-scale immunization program was instituted in spring 1777.

Further Reading

- Todd W. Braisted, ‘The Black Pioneers and Others: The Military Role of Black Loyalists in the American War for Independence’, in John W. Polis, (ed.), Moving On: Black Loyalists in the Afro-Atlantic World (New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1999), 3–37. https://tinyurl.com/Braisted-Black-Pioneers

- Todd W. Braisted, “’Such as are absolutely Free’: Benjamin’s Thompson’s Black Dragoons” “Journal of the American Revolution,” https://tinyurl.com/blkdragoon

- James Corbett David, Dunmore's New World: The Extraordinary Life of a Royal Governor in Revolutionary America--with Jacobites, Counterfeiters, Land Schemes, Shipwrecks, Scalping, Indian Politics, Runaway Slaves, and Two Illegal Royal Weddings (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013).

- Elizabeth A. Fenn, Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775– 82

(New York: Hill and Wang, 2002) - George Fenwick Jones, "The Black Hessians: Negroes Recruited by the Hessians in South Carolina and Other Colonies," The South Carolina Historical Magazine, vol. 83, no. 4 (Oct., 1982), 287- 302. https://www.academia.edu/42860211/The_Black_Hessians_Negroes_Recruited_by_the_Hessians_in_South_Carolina_and_Other_Colonies

- Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1973)

- John U. Rees, ‘They Were Good Soldiers": African–Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775–1783 (Warwick, U.K.: Helion and Company, 2019; U.S. distributor, Casemate Publishing, Inc.)

The author extends his thanks to Todd W. Braisted, Don N. Hagist, Don Troiani, and Gregory J. W. Urwin for their contributions to this work.

Related Battles

1

102