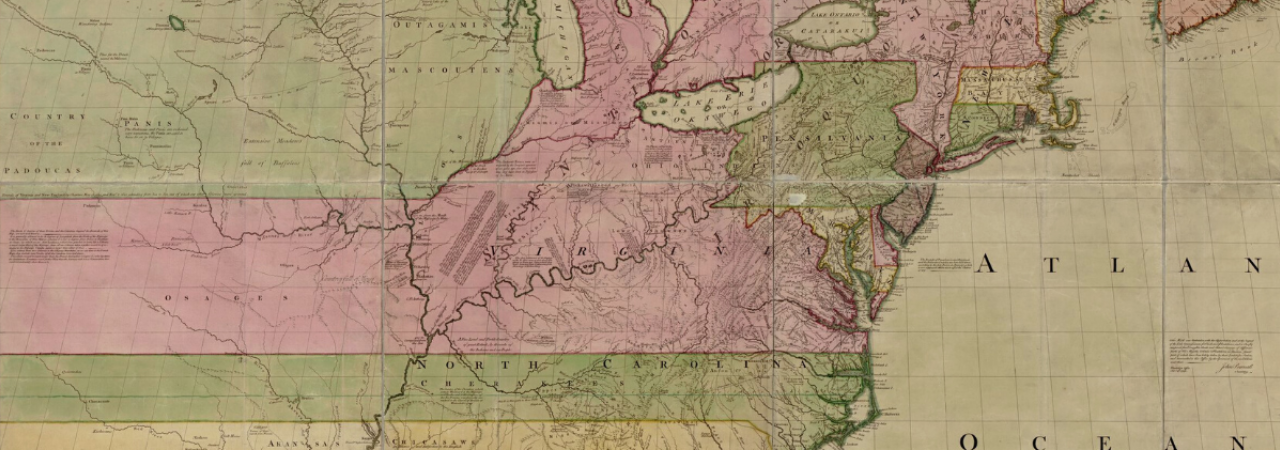

The governors of the Thirteen Colonies were pivotal figures in the period before and after the confrontation at Lexington and Concord. The way that these royal officials responded to the colonists’ challenges to their authority shaped the early months of the Revolutionary War.

General Thomas Gage was the Governor of Massachusetts. Since 1763, Gage had served as the commander-in-chief of British forces in North America. As the highest-ranking British officer in the Thirteen Colonies, Gage had lengthy experience dealing with the tension between the American colonists and the British Empire, especially over the quartering of troops in the colonies. After the Boston Tea Party, General Gage was chosen to replace Thomas Hutchinson as the governor of Massachusetts. To punish Boston, Parliament had passed a series of laws known as the Coercive Acts, which the colonists soon began calling the Intolerable Acts. As governor of Massachusetts, General Gage was responsible for implementing the Acts, which closed the port of Boston and limited the colony’s ability to self-govern. To enforce these laws, Gage withdrew British soldiers from across the colonies and gathered them in Boston. But while the city turned into an armed camp, rebel colonists dismantled royal authority in the rest of the colony. After Lexington and Concord, Gage and his men were besieged in Boston by an army of militiamen. Gage was replaced as commander-in-chief by General William Howe in September 1775, and while he retained the title of governor he spent the rest of the war in Britain.

William Tryon was the Governor of North Carolina and then New York. In both of these colonies, Tryon faced challenges to royal authority from colonists. In North Carolina, Tryon was responsible for suppressing the Regulator movement, which was an uprising in the western portion of the colony sparked by high taxes and corrupt officials. Tryon led a force of militia and defeated the Regulators at the Battle of Alamance on May 16, 1771. Shortly after suppressing the Regulators, Tyron left North Carolina for New York. As governor of New York, he succeeded in convincing the colonial assembly to provide funds for the quartering of British troops, but he was unable to enforce the Tea Act in 1772. In October 1775 Tryon left New York City for the safety aboard a British warship in the harbor. When George Washington marched the Continental Army to New York City, Tryon conspired with the city’s mayor in a failed plot to kidnap or assassinate Washington. In 1777 Tryon was appointed as a commander of Loyalist troops. He led several raids on towns along the Connecticut coast, including Danbury and New Haven, that were notorious for their brutality and deliberate targeting of civilians. In 1780 Tryon returned to Britain, where he would spend the rest of his life.

William Franklin was the Governor of New Jersey and the illegitimate son of Benjamin Franklin. The elder Franklin acknowledged William as his son, and used his influence in the British government to help get him the appointment as governor. As the American Revolution began, father and son found themselves on opposite sides. Benjamin Franklin had become an advocate for American independence, while William Franklin remained convinced that the colonies would be better off remaining in the British Empire. In January 1776, Franklin was placed under house arrest by rebel militiamen. After the Declaration of Independence, he was imprisoned in Connecticut for two years. He spent eight months in solitary confinement as punishment for continuing to secretly communicate with American Loyalists. In 1778, he was released as part of a prisoner exchange and went to New York City. There he became a leader and organizer of Loyalist military units. Franklin left for Britain in 1782, and he spent the life of his life there. He never fully reconciled with his father.

John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore was the Governor of Virginia. In June of 1775, Dunmore and his family left the Governor’s Palace in the colonial capital of Williamsburg for the safety of a British warship offshore, which carried them to the Loyalist stronghold at Norfolk. From this base, Dunmore recruited and organized supporters of the Crown and launched raids against plantations owned by rebels. On November 7, 1775, he signed a proclamation that offered freedom to any enslaved person who escaped from a rebel slaveowner and joined the British. Several hundred escapes slaves were formed into a unit called Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment. On December 9, 1775, at the Battle of Great Bridge, Dunmore’s forces attempted to disperse rebel militia that was gathering outside the town. The rebels repulsed the attack and soon after Dunmore and the Loyalists retreated from Norfolk to the small British fleet offshore. In August of 1776, after several months of launching minor amphibious raids along the Chesapeake Bay coast, Dunmore and his fleet sailed for New York. Dunmore himself returned to Britain, where he continued to receive his governor’s salary of governor until the end of the war.

James Wright was the Governor of Georgia. Georgia was the only colony to successfully implement the Stamp Act of 1765, and it was the only colony that did not send representatives to the First Continental Congress. But the revolutionary spirit eventually reached even this most loyal colony, and in January 1776 Wright was imprisoned by rebel militia. Wright escaped to a British warship and left for Britain. In 1778, Britain launched a campaign to retake the southern colonies. On December 29, 1778, the city of Savannah fell to British forces. Wright returned to the colony in July 1779, becoming the only colonial governor to regain control of his colony during the Revolutionary War. That control, which was never solidified outside the major cities, continued until the British evacuated Savannah in 1782.

Related Battles

1

102

93

300