Artillery Across Three Wars

The artillery park at Valley Forge.

“From some prisoners taken at Corinth it was learned that they were still unnerved from the moral effect of their assaults at Iuka. Those prisoners stated that, as they went into the assault, they recognized the bark of the guns of the Eleventh Ohio. Before these guns they had seen hundreds of their comrades fall like wheat before the harvester. They felt they could not again silence the guns of the Eleventh. It had taken five assaults to do so when the odds were many to one.”

Captain Henry Moore Neil, Eleventh Ohio Battery, remembering a group of Confederate Prisoners taken after the Second Battle of Corinth.

The sounds of the battlefield were every bit as iconic and overwhelming as its sights and smells, and those sounds were dominated by the thundering of artillery fire. By the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775, artillery had been a feature in European warfare almost since the introduction of gunpowder from China. These early, crude pieces (called bombards) were effective against the old-fashioned stone walls and castles of the Late Middle Ages, but they were completely impractical to use on the open field due to their immense size and weight. That changed in the 17th century during the height of the Thirty Years War, where the Swedish Army under King Gustavus Adolphus, "The Lion of the North," developed lighter cannon that could be moved into position quickly and efficiently, while still inflicting tremendous damage on tightly packed enemy formations. From that point onwards, artillery was used in much the same way for the rest of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The cannon of the Revolutionary War came in three main designs, and their functions depended on their projectile trajectory. The standard cannon (field guns) were used on buildings and infantry in a mostly flat trajectory known as direct fire. Field guns could fire two forms of ammunition. Roundshot, or cannonballs, were large pieces of iron or lead at infantry or fortifications. Canister or grapeshot was also fired at infantry, but involved firing a number of smaller balls that would spread outwards in a cone like a giant shotgun, a devastating weapon at close range.

Mortars and howitzers fired at a much higher angle. This meant that they usually had shorter range than a cannon, but could shoot over the heads of friendly troops. Mortars greatly resembled the oldest gunpowder artillery pieces, and typically fired a solid ball nearly one mile into the air. Once the ball reached its apex, gravity took hold and drew the shot down onto the target, devastating enemy fortifications. They also fired a kind of bomb that would explode on a timed fuse as well.

The War of 1812, as well as the contemporary Napoleonic Wars, had artillery function in much the same way. It did see the use of two important technological changes, one of which had a surprising effect on the United States. The first change was the development of "spherical case shot" with shrapnel, developed by a British surgeon named Henry Shrapnel. Spherical case functioned similarly to the bombs used previously: they were round objects with the thin shell that would explode via fuse. Instead of being simply filled with black powder, however, spherical case was filled with small chunks of metal, eventually named after Shrapnel, that would fly out in random directions, causing grievous injuries to anyone nearby. The other development was the use of rocket artillery, specifically the Congreve rocket. Although their invention was attributed to Sir William Congreve, they are virtually identical to the rockets used on British troops in India. When lit, the rocket would propel itself from a metal tube or trough, supported by a wooden tripod, and explode on impact. This made them much lighter and more maneuverable than any cannon and potentially had a much higher rate of fire, but they had much lower range and sometimes abysmal accuracy, and so the concept was never widely adopted in the 19th century. The rockets were used extensively at the Battle of Fort McHenry, where one witness, Francis Scott Key of Baltimore, included them in a line for his commemorative poem:

"And the rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night, that our flag was still there."

The poem would go on to become the United States' national anthem, and the "rockets' red glare" is included in most sung versions to this day.

Artillery in the Civil War, tactically speaking, was used in much the same way as the other wars, but the technological developments that were used it in had profound effects during the course of the fighting, and would lead to even greater changes later on. The most famous change was, of course, the widespread use of rifling guns, through which pieces were lined with spiral groves along the interior, causing the shells it fired to spin like a football which stabilized the flight path and led to much greater range and accuracy. The Parrott Rifle and the 3-inch Ordinance Rifle were used mostly by Civil War armies and mostly in the North.. It was expensive and complicated to produce, requiring complex machinery to ensure it remained reliable and durable in battle, which only the Northern industrial capacity was capable of providing. In fact, the more heavily industrialized economy in the Northern states ensured Union superiority in artillery throughout the war. Both sides still fielded other rifled guns, like the inexpensive but unreliable Parrott rifle, in addition to smoothbore designs like the Napoleon cannon.

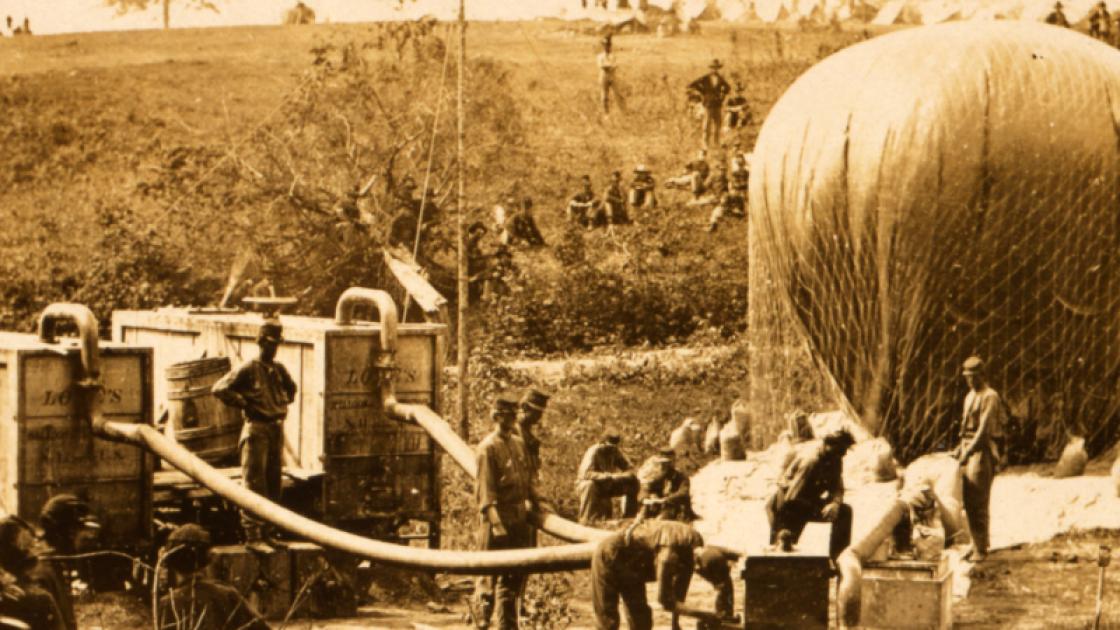

The major tactical change in the Civil War, came in the development of indirect fire. Indirect fire, using artillery to target enemies not within eyesight, had been done before, but artillery officers in the Civil War experimented in ways to use it effectively, most notably with the use of hot air balloons to spot formations, and communicate via signal flags to their own artillery crews on where to aim. Though not entirely successful, Civil War military ballooning was a major first step in aerial warfare.

The artillery tactics used in these three wars were slow to adapt to the various technological changes, if they adapted at all. Yet we cannot expect officers to grasp the full potential of their new weapons in the moment. The new developments lead, in later decades, to even more radical change as artillery became even more accurate at further ranges, new types of ammunition were introduced, and indirect fire was successfully reduced to a science. Even rocketry would eventually return to prominence on the battlefield during the Second World War. It was up to those that followed after the Civil War artillerymen to learn from their experiences, and adjust course accordingly.