Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key was born on August 1, 1779. His father, John Ross Key, had just returned from being a second lieutenant in Captain Thomas Price’s Maryland Rifle Company during the Revolutionary War, when Francis was born at the family mansion “Terra Rubra” in Frederick County, Maryland, now known as Carroll County. While the war continued, Francis Key grew up on the family estates. At the age of 10 he was sent to Annapolis, Maryland, to attend grammar school, and later St. John’s College—graduating from the latter in 1796. After graduation, he stayed with his paternal uncle Philip Barton Key to practice law. (Francis later named his son Philip Barton Key II in honor of his uncle. The younger Philip Barton Key was caught in an infamous Washington, DC, love triangle in the 1850s and was killed in broad daylight by Congressman and later Civil War general Daniel Sickles, in Lafayette Square, on February 27, 1859.) After passing the bar in 1801, he settled in Georgetown, DC, which at that time was an independent municipality. After starting a thriving law practice Key married Mary “Polly” Taylor Lloyd. The couple had eleven children.

Throughout his life, Key was a devout Episcopalian and he almost became a priest instead of a lawyer after graduating from St. John’s. Because of his religious beliefs, he also opposed the armed conflict known as the War of 1812. Regardless of his beliefs, the lawyer turned to soldiers, and enlisted with the Georgetown Light Field Artillery.

As a lawyer and a soldier, Key was chosen to help negotiate a prisoner exchange with British prisoner exchange agent Colonel John Stuart Skinner. The negotiations focused on the release of Dr. William Beanes, a Maryland physician and colleague of Key.

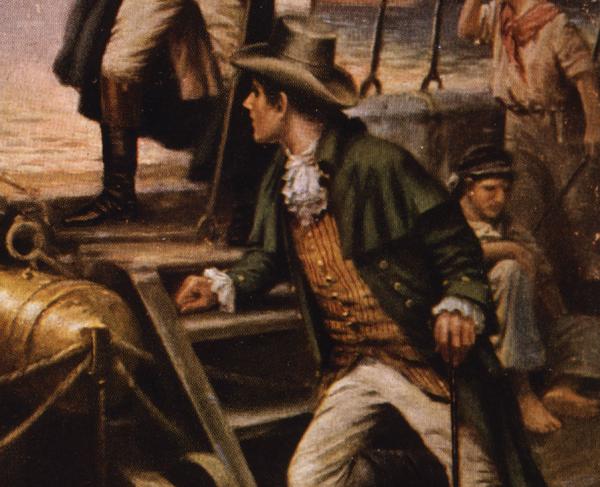

On September 5, 1814, Key and Skinner boarded the British HMS Tonnant stationed in the Baltimore Harbor in order to facilitate the exchange. The two sides came to an agreement and Beanes was set to be released; however, the British, who were in the midst of an active military campaign, were worried that the ship’s location had been compromised and would not allow Key, Skinner, or Beanes to return to shore.

On September 13th, the British opened a bombardment on Fort McHenry, as part of the larger Battle of Baltimore to control the city and the surrounding harbor. The British fired at the fort all night but could not overtake the fort. The next day, as the smoke from the artillery cleared, Key, Skinner, and Beanes could see an oversized American garrison flag flying over the fort. The British, knowing they didn’t have enough manpower to overtake the fort, withdrew. With this loss, the Battle of Baltimore ceased and the British fleet set sail for New Orleans.

Inspired by the events in Baltimore Harbor, Key wrote the poem “Defence of Fort M’Henry” and overlaid it with the popular tune from the song “To Anacreon in Heaven.” This song was written and composed in 1778 and 1780 respectively by Ralph Tomlinson and John Stafford Smith as the theme song for the Anacreontic Society, a London gentlemen's society that met monthly between 1766-1791 to discuss music. After its conclusion, the song was still popular in the United Kingdom and the Thirteen Colonies. On September 20, the “Defence of Fort M’Henry” was published by the Baltimore Patriot. This song was published as “The Star-Spangled Banner” by 1814.

While this was a popular song, it did not officially become the United States National anthem until March 3, 1931. During the interim, “Hail Columbia” and “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” were the de facto anthems. “Hail, Columbia!” was composed by Philip Phile in 1789 for George Washington’s inauguration as “The President’s March” and rearranged to by Joseph Hopkinson later that year. This song is still played to honor and introduce the Vice President. The motto “In God we Trust” may have been adapted from the line “In God is our Trust” in the fourth stanza of Key’s poem. The motto was codified in 1956 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and became the official motto for the United States. Before 1956, “E Pluribus Unum,” translated as “from many, one,” was the de facto motto and was approved by an Act of Congress in 1782 to be used on the national seal and coinage.

After the war, Key went back to his law practice. He argued in front of the Supreme Court multiple times, such as during Aaron Burr’s conspiracy trials in 1807, and gave legal counsel to President Andrew Jackson’s cabinet during the Petticoat Affair concerning Secretary of War John Eaten and his wife Peggy O’Neal. In addition, he prosecuted Richard Lawrence for his assassination attempt on President Jackson in 1833, and later Key served as the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia from 1833 to 1841.

During this time, slavery was a prominent legal issue. In 1816, Key helped found the American Colonization Society that promoted the emigration of African Americans from the United States to Africa. His family were slave owners and Key personally owned slaves until he freed them in 1830. As Attorney of DC, he prosecuted abolitionists and supported strict slave laws. Throughout his life he had varying, and contradictory, views on slavery, which mirrored the nation’s complex relationship with the institution leading toward the Civil War.

On January 11, 1843, Key died at the age of 63. While a prominent lawyer and figure in his own right, he also leaves behind the legacy as the writer of the United States National Anthem. Today, this anthem is synonymous with patriotism. With any symbol, it has been the means of veneration of the United States and protests for the country’s policies and procedures.

The lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner” go as followed:

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream,

’Tis the star-spangled banner - O long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore,

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a Country should leave us no more?

Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

O thus be it ever when freemen shall stand

Between their lov’d home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with vict’ry and peace may the heav’n rescued land

Praise the power that hath made and preserv’d us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto - “In God is our trust,”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.