The Battle of Bemis Heights

Shortly after the bloody fighting at the Battle of Freeman’s Farm on September 19, 1777, General John Burgoyne wanted to renew his assault on the American position. Before he ordered the assault though, he learned that General Sir Henry Clinton in New York City was going to make a move up the Hudson and attack some of the American forts in the lower Hudson. While it was unlikely his force would be able to make it up to Saratoga in time to assist Burgoyne, he hoped news of the attack may potentially draw off some of General Horatio Gates’ men from their strong position at Bemis Heights. Both sides settled into a stalemate at Saratoga which would last for three weeks. During this interlude, there was constant picket and patrol firing between the two armies as neither budged. The British fortified their position at Freeman’s Farm. At Freeman’s Farm, they built the Balcarres redoubt, named after General Lord Balcarres (also known as the Light Infantry Redoubt) and to its right they constructed the Breymann Redoubt named after Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann.

During this time, drama in the American camp threatened chances of an American victory at Saratoga. Gates wrote to the Congress about the action at Freeman’s Farm, but jealously refused to mention Arnold’s name, which led to a heated exchange between the two American generals. Arnold was also replaced by General Benjamin Lincoln. Lincoln, outranked Arnold and was therefore elevated to be Gates' second in command when Lincoln arrived at army headquarters. Arnold had proved to be the most capable officer in Gates’ army, but the two men traded barbs from late September until at least October 1, 1777. Arnold threatened to leave the army, but officers petitioned him to stay.

As the British continued to wait for help from Clinton, their supplies began to run low. By early October, Burgoyne was running out of options and either needed to drive the Americans out or retreat. Not wanting to retreat from their bloodily won position, he chose to perform an all-out assault on the American Army. His officers though balked at the idea based on their lack of information and after the deadly fighting at Freeman’s Farm. Burgoyne instead decided to attempt another reconnaissance in force on the American left flank.

On the morning of October 7, 1777, 1,500 men under the command of General Simon Fraser moved out from the British fortifications towards the American left flank. This foray included nearly a third of Burgoyne’s army. Fraser’s men advanced three-quarters of a mile outside their entrenchments and deployed into a battle line at Barber’s Wheatfield. On his left, Fraser had British grenadiers under the command of Major John Dyke Acland, in his center German troops, and on his right Light Infantry under the command of General Lord Balcarres. Gates, seeing the British advance, dispatched Daniel Morgan’s men to attack the British force.

The battle began a little after 2 p.m. Morgan was joined by Major Henry Dearborn who commanded light infantrymen armed with muskets and bayonets. They would work in tandem with Morgan’s riflemen. While the rifles were more accurate, after firing, when they needed to reload, they could fall behind Dearborn’s bayonets to prevent the British from driving them away. At this engagement, it worked perfectly for the Americans. Morgan and Dearborn fired on Balcarres’ men on the British right and a brigade of Americans under General Enoch Poor assaulted the British left while Americans under General Ebenezer Learned assaulted the British center.

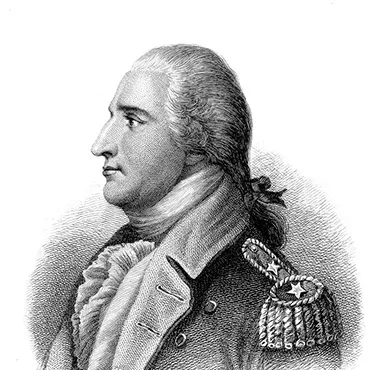

While having lunch together, Gates, Lincoln, and Arnold could hear the growing sounds of battle. Arnold urged Gates to allow him to take the fight to the enemy. Gates initially hesitated, later telling Arnold that he was unsure that he could trust him not to bring on a full-scale battle. Arnold assured his commander that he would not, and Gates allowed Arnold to take to the field. General Benedict Arnold rode onto the field to encourage the men in battle. Cheers went up along the American lines as Arnold rode into the fight. Heavy firing erupted all along the British line. On the British left, the grenadiers under Acland were having a difficult time with Enoch Poor’s men. Acland ordered a bayonet charge but as they advanced Acland fell wounded and many of his grenadiers were felled wounded or dead. The British left began to collapse. On the right, Morgan and Dearborn were proving to be incredibly effective in breaking up the British formations. General Fraser tried to move his men west but was repeatedly repulsed. With both flanks crumbling, Burgoyne rode back to the British entrenchments to prepare for a defense.

Soon the Americans had broken both flanks and the British began to withdraw in disorder. As Fraser’s men began falling back from Barber’s Wheatfield, Fraser attempt to reform his lines between the wheatfield and the British fortifications. At this moment, one of Morgan’s riflemen (often identified as Timothy Murphy) fired and hit General Fraser in the stomach and he fell from his horse mortally wounded. At this moment the British lost all order and broke and ran for their lines at Freeman’s Farm. The Americans, urged on by Arnold, closely followed.

Although Burgoyne’s reconnaissance had been repulsed, Arnold wanted to take the British fortifications in front of him. He ordered his men to assault the Balcarres’ redoubt. The British though put a determined stand against the surging Americans and halted Poor’s men from taking the fort. As the American attack stalled at the Balcarres’ redoubt, Arnold rode forward with men from Learned’s brigade to take the Breymann redoubt on the British Army’s extreme right flank. Assaulted by Morgan’s men on their right and Learned’s men on their left, the small German garrison of the Breymann Redoubt was pushed back. The Americans took the redoubt and continued to push the Germans back. Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann himself was killed by his own men after he had killed four of them who were attempting to retreat. As the charge continued past the redoubt, a musket ball struck Arnold in the leg and he fell to the ground with his horse. The Germans fell back, and the Americans now held a position on the British flank as the sun set and darkness covered the ground.

The battle had been a disaster for Burgoyne’s army. Burgoyne had lost more than 600 men killed, wounded, or captured. General Fraser died later that night and Burgoyne himself had almost been killed on multiple occasions during the intense fighting. Gates had lost about 150 men killed and wounded during the fighting that day.

With his right flank exposed, Burgoyne removed his men from the Balcarres’ redoubt that night, and the next day his battered army began the retreat north. Burgoyne and his 5,000 man army fell back towards to Saratoga (modern-day Schuylerville) and was surrounded by Gates’ army. On October 13, 1777, Burgoyne with no other options left, offered to open negotiations with Gates. After a couple of days of negotiating, Burgoyne agreed to surrender with the condition that his men would be paroled and return to England. Congress would later go back on this parole and Burgoyne’s men would spend the rest of the war in American prisoner-of-war camps. On October 17, 1777, Burgoyne and his 5,000 man army officially surrendered to Gates. This was the first British Army to surrender in world history and marked a major turning point in the Revolutionary War.

Further Reading:

-

Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War By: Richard Ketchum.

-

With Musket & Tomahawk Volume I: The Saratoga Campaign and the Wilderness War of 1777 By: Michael O. Logusz

-

The Compleat Victory: Saratoga and the American Revolution By: Kevin J. Weddle.

Related Battles

330

1,135