“The Battle of Brandy Station”

The Civil War Trust had a chance to sit down with noted Civil War cavalry historian and Trust member Eric Wittenberg, author of “The Battle of Brandy Station: North America's Largest Cavalry Battle.”

Civil War Trust: Eric, in 2006 you published “The Union Cavalry Comes of Age: Hartwood Church to Brandy Station, 1863” which included a great account of the Battle of Brandy Station. What made you want to revisit Brandy Station in your new book?

Eric Wittenberg: The way that I really learn about something is to research and write about it. By immersing myself in Brandy Station, and then by putting together the walking/driving tour, I had to really learn the battle in much great depth than ever before. I also thought that there was a niche for a mid-length tactical treatment on Brandy Station.

I also really enjoy telling the stories of the soldiers who fought these battles. More than most cavalry fights, Brandy Station was filled with examples of one-on-one combat, and there are tons of wonderful stories to tell. There’s no shortage of drama, and there’s no shortage of colorful personalities. The story almost tells itself.

Civil War Trust: The Battle of Brandy Station (June 9, 1863) was fought between the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. Help set the stage for this battle. What were the Union and Confederate cavalry forces doing at this time?

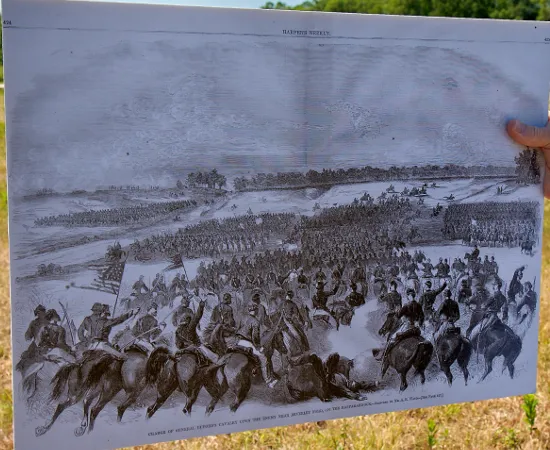

Eric Wittenberg: Robert E. Lee had ordered the Confederate cavalry to concentrate in Culpeper County, Virginia in anticipation of the forthcoming invasion of Pennsylvania. Five of the seven brigades of cavalry assigned to the Army of Northern Virginia came together there, forming the largest force of cavalry ever fielded by a Confederate army.

The Union cavalry was desperately trying to locate the main body of Lee’s army, trying to figure out what his intentions were. When it became obvious that the Confederate cavalry had concentrated, Joseph Hooker, who still commanded the Army of the Potomac at that time, grew worried that Jeb Stuart was preparing to launch a massive raid, and he decided to act. Hooker ordered the Union cavalry to destroy or disperse the great force of Southern horse soldiers that had gathered in Culpeper County, and that set the stage for the largest cavalry battle ever seen on the North American continent.

Civil War Trust: Prior to the battle J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry forces were engaged in several pomp-filled grand reviews and gallant balls around Culpeper. Did all of these social events impact the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry’s preparedness for the Battle of Brandy Station?

Eric Wittenberg: That’s an interesting question. The reviews served a purpose. They allowed first Stuart and then General Lee to see how well equipped and how well-prepared the Southern cavalry was, and it also provided Lee with an opportunity to ask the Confederate supply department to provide more and better ammunition to Stuart’s cavalry. All of those things are positive consequences of the reviews.

The flip side of that coin, however, is that the preparations distracted Stuart and his command such that they did not notice the approach of 12,000 Union horse soldiers. The reviews and the pomp and circumstance also tired out men and horses such that they were not at their peak of readiness when the Union cavalry splashed across the Rappahannock River on the morning of June 9, 1863.

Civil War Trust: In your book you describe Alfred Pleasonton’s Union attack plan at Brandy Station as an excellent one, but “based on flawed intelligence.” What were those key intelligence failings and how did it impact the Union attack?

Eric Wittenberg: Pleasonton’s plan was to divide his force into two wings, one of which would cross the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford and the other one would cross at Beverly’s Ford, which is eight miles upriver. The two forces would then converge on the town of Culpeper. Pleasonton assumed that the Confederate cavalry was occupying Culpeper and nowhere near the banks of the river.

The reality was that the Confederate cavalry was encamped near the river crossings, and the fords were picketed. So, instead of making easy, uncontested crossings and leisurely advancing on Culpeper, the Federal cavalry came under heavy fire immediately after crossing the river. The Union right wing not only had to deal with three brigades of Confederate cavalry, it also had to deal with all of the Southern horse artillery, which was camped near Beverly’s Ford.

The plan was well-conceived and well-considered, but it was based on flawed assumptions. Those flawed assumptions, in turn, doomed the plan to failure

Civil War Trust: Wasn’t the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry superior to its Union counterparts? If so how was it that the Confederates were so surprised by this large Union attack on June 9, 1863?

Eric Wittenberg: For the first couple of years of the war, Jeb Stuart and his cavaliers literally rode circles around their Union counterparts. There are lots of reasons for that. First, and foremost, the Union cavalry was not concentrated and formed into a cohesive command structure until Hooker ordered the formation of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps in February 1863. Until then, the Union cavalry was parceled out in dribs and drabs and was not a cohesive command. In addition, it took time for competent subordinate leadership to emerge. That process began before March 1863, but really accelerated with the March 17, 1863 Battle of Kelly’s Ford, where, for the first time, the Union cavalry went boot-to-boot with the Confederate cavalry, giving as well as it got. Finally, the Union cavalry had superior armaments, and those armaments eventually tipped the balance toward the Union’s favor.

Civil War Trust: Many know of Brig. Gen. John Buford’s exploits at Gettysburg, but he was also a key figure at Brandy Station. How would you rate his performance here?

Eric Wittenberg: John Buford had a very difficult day at Brandy Station. First, his command was left to fight alone for most of the morning when Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg’s command did not arrive when it was supposed to arrive. That permitted Stuart to devote all of this attention to Buford’s command. In addition, for a large portion of the day, Buford was encumbered by Alfred Pleasonton, who attached himself to Buford’s command post and kept him tethered. Buford was very aggressive by nature, and he wanted to attack with his whole force, and Pleasonton would not permit him to do so until well after Gregg’s force finally arrived.

At the same time, Buford and his troopers spent fourteen long, hard hours fighting that day, and they did so very effectively. If there were any questions about Buford’s talents as a battlefield commander, they were answered at Brandy Station.

Civil War Trust: In your account you credit Maj. Robert Beckham and his Confederate horse artillerists for playing a critical role at Brandy Station. How did these Southern artillerists affect the battle?

Eric Wittenberg: The Confederate horse artillery almost single-handedly held off Buford’s initial assaults at St. James Church, and one of the Confederate gunners held off Gregg’s initial advance on Fleetwood Hill later in the morning. Those horse artillerists really tipped the balance that day, and that’s a tribute to Beckham and his battery commanders.

Civil War Trust: There has been much discussion over JEB Stuart’s generalship at Brandy Station. How would you rate his actions?

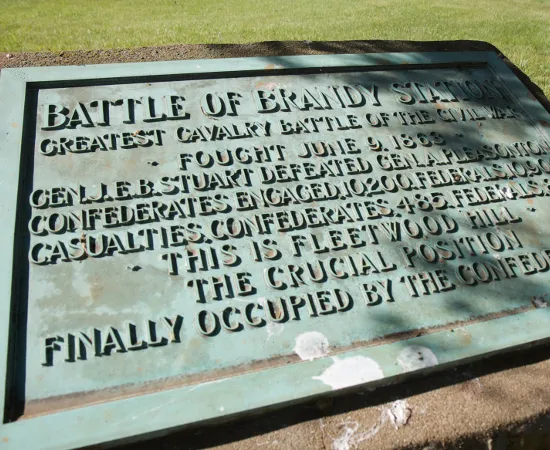

Eric Wittenberg: Brandy Station showed Stuart at his worst and at his best. He was caught by surprise and was nearly defeated on one hand. On the other hand, once he figured out where things stood, he fought an excellent battle and ended up in possession of the battlefield at the end of the day, having utterly frustrated the Union’s objections for the expedition.

Civil War Trust: Despite their failure to beat Stuart’s horsemen this day, you point to the Battle of Brandy Station as a key turning point for the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry. Tell us more about these improvements.

Eric Wittenberg: Brandy Station clearly demonstrates the maturation of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps. It fought long and hard against the Confederate cavalry that day on equal terms. While the Union cavalry lost the battle, their performance that day worked wonders for the morale of the blue clad troopers. From that day forward, the Northern horsemen were at least the equal of their Southern counterparts, and by the end of the war, the Union cavalry was the largest, best mounted, and best equipped cavalry force the world had ever seen. Brandy Station was the tipping point in that maturation process.

Civil War Trust: What about the engagement at Stevensburg? Few people know about it.

Eric Wittenberg: The division of French Col. Alfred N. Duffié had a difficult task. Under Pleasonton’s plan for the Cavalry Corps, Duffié’s division was to cross the river at Kelly’s Ford and then head for Stevensburg. The Frenchman was to protect Gregg’s flank and then rejoin the main column at Culpeper. Col. Matthew C. Butler, with a single regiment, held Duffié up for most of the day, and prevented Duffié’s division from reaching Fleetwood Hill until after Gregg had broken off and begun withdrawing from the field. Along the way, the story at Stevensburg features great drama, including the story of how a single Union artillery shell killed one Confederate officer, two horses, and took off Butler’s foot.

Civil War Trust: Eric, swirling cavalry battles, with their ever-changing lines and swift movements must pose a particular challenge to the modern historian. How difficult was it to piece together the narrative of this battle?

Eric Wittenberg: Trying to make sense out of a large and complicated battle like Brandy Station is a real challenge. It proves the truth of something I have long believed, which is that one cannot truly understand what happened on Civil War battlefields without understanding the terrain. The terrain drives the action, not vice versa. Fortunately, we still have an intact battlefield at Brandy Station to enable us to evaluate the terrain. The battlefield is the best classroom possible. I had to make heads and tails out of all of it.

Civil War Trust: What research hurdles did you face in putting together this book?

Eric Wittenberg: Researching a battle that involved 21,000 men can be a real challenge because there is a plethora of available sources. Finding the sources, corroborating them, and then weaving them into a coherent narrative was a real challenge. But it was the sort of challenge that I enjoy.

Civil War Trust: This book, like many of your others, includes a walking and driving tour for the Brandy Station battlefield. What can the visitor see at Brandy Station?

Eric Wittenberg: Fortunately, most of the battlefield is intact and in pristine condition. The efforts of the Civil War Trust and the Brandy Station Foundation have preserved this battlefield for generations to come. A major portion of the battlefield is owned by the Civil War Trust, which has installed walking trails and interpretation. Some of the battlefield is entirely in private hands and, while the people who own those portions are friendly to battlefield preservation, it’s important not to take advantage of them and avoid trespassing on private property.

Civil War Trust: As a longtime member and supporter of the Civil War Trust what would be your vision for the Brandy Station battlefield?

Eric Wittenberg: There’s still plenty of work to be done at Brandy Station. Significant portions of the battlefield remained threatened, and most of it remains in private hands. Our task, as preservationists, is to find a way to preserve the rest of the battlefield for the generations that will follow us. I would like to see the northern end of the battlefield safely preserved and available to public visitation.

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...