The Battle of Glorieta

Don E. Alberts

Two weeks before the great Battle of Shiloh, Union and Confederate troops in the far-off New Mexico Territory fought the key battle of the Civil War’s westernmost campaign. At stake was control of the vast, sparsely populated but mineral rich region that is today’s Southwest and Intermountain West. The invasion of New Mexico by Confederate Texans was probably the South’s only attempt to conquer and occupy Union territory. It was also one of very few, if not the only, logistically driven campaigns of the war, thanks to New Mexico’s harsh conditions: its remoteness, bare subsistence agriculture, few roads and lack of navigable rivers. Obviously, any Confederate commander planning to invade would have to take these factors into account.

Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley, a former regular army officer serving in New Mexico, resigned his commission and traveled to the Confederate capital to present such a plan to Jefferson Davis. Sibley proposed to lead a mounted force to New Mexico, live off the land, defeat the Federal forces encountered and secure the military supplies and natural resources of the territory (encompassing modern New Mexico and Arizona, as well as part of Nevada) for the Confederacy. He would then march north, capture the rich mines of the Colorado Territory and proceed west through Salt Lake City and across the Sierras to occupy the California seaports of Los Angeles and San Diego. In one stroke, Sibley would bring the entire Southwest, its gold and silver and the terminus of the transcontinental railroad under Confederate control. Though farfetched, the scheme cost the Southern treasury little and retained the possibility of a sizable return. It was approved, and Davis commissioned Sibley a brigadier general, giving him authority to raise a mounted brigade in Texas for the campaign.

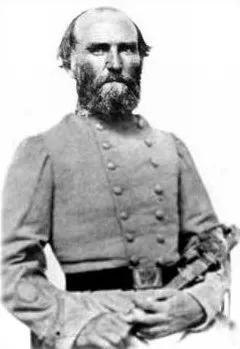

Sibley was poorly suited to the task. A heavy-drinking dragoon officer, his soldiers came to describe him as a “walking whiskey keg,” or a dreamer prone to let the morrow take care of itself. Nonetheless, during the late summer and early autumn of 1861, he raised a brigade of three mounted regiments, the 4th, 5th and 7th Texas Mounted Volunteers, along with supporting artillery and supply units.

These troops were among the best volunteers answering the Southern call to arms and soon matured into excellent soldiers. Field officers were almost all experienced as Indian fighters or Mexican War veterans. Col. James Reily commanded the 4th Texas, but was absent on diplomatic duties in Mexico during the New Mexico Campaign, and Lt. Col. William R. Scurry led the regiment in his stead. Prominent state politician and hero Tom Green was colonel of the 5th Texas, while Col. William Steele commanded the 7th Texas.

In late October Sibley marched west from San Antonio, Texas, along the Overland Stage Road to abandoned Federal Fort Bliss, near present-day El Paso, arriving just before Christmas 1861. Soon the straggling Confederate column stretched farther into southern New Mexico along the Rio Grande.

The invaders had been preceded that summer by Col. John R. Baylor and a handful of troops from the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles and associated artillery units. After capturing the territory’s southernmost Federal post, Fort Fillmore, Baylor called for reinforcements to help secure his conquests from Union forces at Fort Craig. Sibley’s brigade was that reinforcement, though the general quickly supplanted Baylor as overall commander.

With approximately 2,500 mounted men, 15 pieces of artillery, and an extensive supply train, Sibley anticipated an easy conquest of New Mexico. His immediate goal was the capture of Fort Craig to the north, which would open the road to the Federal supply depot at Albuquerque and the territorial capital at Santa Fe, along with nearby Fort Marcy. The Texans would then advance into northeastern New Mexico and capture the Federal supply center at Fort Union. Capture of the military goods and food there was absolutely necessary for Sibley’s plan to invade Colorado and secure the wealth of its booming mining regions for the Confederacy. In early February 1862, Sibley left Col. Steele and half the 7th Texas at Fort Bliss and moved north.

In the interim, the Union commander of the Department of New Mexico, Col. Edward R. S. Canby, a calm and experienced Mexican War veteran, had called up militia and volunteer forces to augment the garrison at Fort Craig. He also requested that the governor of Colorado send to the defense of New Mexico “as large a force of Colorado volunteers as can possibly be spared.” By February, an independent company of Coloradoans arrived, bringing Canby’s strength to approximately 3,800 men, some 1,200 of them seasoned regulars. Further north, an entire regiment of rugged miners and frontiersmen, the 1st Colorado Volunteers, moved south to help hold New Mexico for the Union.

Upon reaching Fort Craig, Sibley realized the position was too strong to be taken by direct assault and decided to bypass the post, threaten its supply lines north to Albuquerque and Fort Union, and force the enemy into a major battle to keep those lines open.

That plan worked. The Battle of Valverde, fought in the Rio Grande bottomlands north of Fort Craig on February 21, was the largest and westernmost battle of the Civil War campaign in New Mexico. The fortunes of war swayed repeatedly, but by evening the Texans had captured one of the two Union artillery batteries and driven Canby back to Fort Craig. It was an impressive tactical success for the Confederates, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. The Union forces were damaged, but not destroyed, and Fort Craig stood across the Rebels’ supply line.

The Texans faced a serious dilemma. They could try to retreat back to the scanty supplies left behind in southern New Mexico, although a still-strong enemy force now lay across their line of retreat, or they could continue northward, leaving that force in their rear and hoping to capture Federal supplies at Albuquerque, Santa Fe and Fort Union. Encouraged by his key lieutenants, and carrying only five days’ rations for men and animals, Sibley decided to press on.

The Confederate advance party entered Albuquerque on March 2, only to find that Union forces had removed or destroyed almost all the military supplies there. Nevertheless, they raised the Confederate flag over the town plaza while a small band played “Dixie.” Sibley established his headquarters and a hospital near the burned and abandoned Federal depot, sent soldiers scouring the vicinity for supplies and hastened an advance party of the 2nd and 5th Texas to occupy Santa Fe and hopefully secure additional supplies.

The Confederate presence disturbed many residents of the capital. Mother Magdalen Hayden of the Loretto Academy wrote:

Our poor and distant territory has not been spared. The Texans, without any provocation, have sacked and almost ruined the richest portions and have forced the most respectable families to flee from their homes, not precisely by bad treatment, but by obliging them to deliver to them huge sums of money...The terror which I felt is inexpressible.

However, Santa Fe was almost devoid of useful supplies, with nearby Fort Marcy abandoned and the territorial government removed to the protection of Fort Union.

Still, through purchase or confiscation, the Texans managed to accumulate about 40 days’ worth of supplies, which Sibley considered adequate to continue his advance to Fort Union. His vanguard, commanded by Maj. Charles L. Pyron of the 2nd Texas and augmented by an irregular unit known as the “Brigands” or “Company of Santa Fe Gamblers,” was already in the capital and on the Santa Fe Trail, the military highway to Fort Union. Sibley had already sent the bulk of his brigade, a field column commanded by Lt. Col. Scurry of the 4th Texas, to the east side of the Sandia Mountains near Albuquerque in preparation for the advance. On March 12, soldiers of this column, approximately 1,000 men of the 4th and 7th Texas regiments, with accompanying artillery and wagon train, began moving toward the Santa Fe Trail, some twelve miles east of the capital. Sibley remained in Albuquerque with more than half of the 5th Texas and a company of the 4th Texas guarding the supplies.

Soon Pyron heard persistent rumors from civilian travelers along the Santa Fe Trail that a Union force was advancing toward him. An aggressive commander, he left the town early on the morning of March 25 and marched to meet his oncoming enemies in the mountains southeast of Santa Fe, where the constricted canyons along the Santa Fe Trail might neutralize the Federals’ anticipated numerical advantage. By nightfall, Pyron camped near Johnson’s Ranch, a way station near the present-day village of Canoncito. Though inaccurate, his information was based in fact, and the enemy was near.

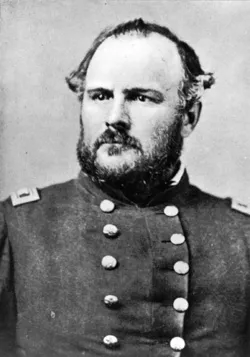

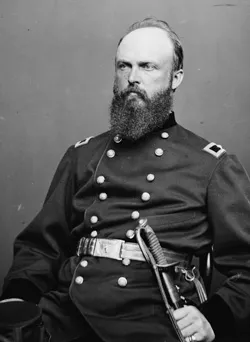

While the Confederates moved slowly northward after the Battle of Valverde, encountering harsh, snowy winter weather along with much resulting sickness, the Federals had not been idle. In addition to the independent company of Colorado volunteers that had already seen action at Valverde, a newly raised full regiment of reinforcements was on the march. The soldiers of the 1st Colorado Volunteers were mostly rugged miners and frontiersmen from the mining districts around Denver City. They were accustomed to loose discipline, firearms and hard work. Their company grade officers had similar backgrounds and generally related easily to their men. Denver attorney John P. Slough, inexperienced in military matters but flexible and well read, was appointed colonel of the regiment, with Lt. Col. Samuel F. Tappan as his second-in-command. The remaining field officer was Maj. John M. Chivington. Often referred to as the “Fighting Parson,” he had been a missionary and was an administrator for the Methodist Church in Colorado when he was chosen to round out the regiment’s roster of field officers. His gregarious nature was popular with both enlisted men and officers.

In late February 1862, the new Union regiment, over 900 strong and with its Company F mounted and equipped as cavalry, left Denver City to reinforce Fort Union, 300 miles to the south. Experiencing the same nasty, late-winter weather that had also assailed the Texans in the mountains east of Albuquerque, the exhausted volunteers reached the Federal post on March 11. For a week and a half, their only major occupation was to be issued uniforms and arms for the upcoming fight they expected.

The 1st Colorado volunteers and the regulars garrisoning Fort Union were anxious to find and fight the Rebels. Though the Department of New Mexico’s overall commander, Col. Canby, had warned against leaving that vital post undefended in the face of the oncoming Confederates, Col. Slough, senior in date of rank to the fort’s commander, Col. Gabriel Paul, decided that defense of Fort Union was best accomplished by advancing a field column westward toward Santa Fe, where the Rebels were reported to be. He would then, in compliance with Canby’s orders, “act independently against the enemy” and harass, obstruct the movements of and perhaps cut off the supplies of his foe through what was essentially a reconnaissance in force. On March 22, the Union field column moved south on the Santa Fe Trail, the only useful road to the capital, leaving a handful of defenders at Fort Union.

Slough had approximately 1,340 men under his command, with three companies of regular army infantry and a squadron of regular cavalry strengthening and lending experience to the raw 1st Colorado. Moreover, Capt. John F. Ritter commanded a four-piece “heavy” battery of six-pounder guns and 12-pounder field howitzers, while Lt. Ira W. Claflin led a “light” battery of four 12-pounder mountain howitzers. A 100-wagon supply and support train accompanied the field column.

The Santa Fe Trail between Fort Union and Santa Fe was a military road, rebuilt and maintained by the army and intended to facilitate travel of military units between those two points. The Federal column thus made good time, reaching Bernal Springs, some 45 miles out of Fort Union on the afternoon of March 24. Here the road turned abruptly to the west and northwest toward Glorieta Pass. Here also Slough organized an advance party of 418 volunteer and regular infantry and cavalry, under command of Maj. Chivington, to advance toward Santa Fe and discover the whereabouts of the Confederates.

Chivington’s vanguard reached Kozlowski’s Ranch, a major way station on the Santa Fe Trail late on March 25. Simultaneously, Maj. Pyron’s Texan vanguard was making camp at Johnson’s Ranch, near the western entrance to Apache Canyon and Glorieta Pass, while Scurry’s main body of Confederates was near the village of Galisteo, 12 miles to the south. Since the Federal party that night slept near the eastern entrance to that same canyon and pass, if either force or both continued to advance, a clash was inevitable.

After a very cold night, clear dawn brought the shivering soldiers around their fires for a quick breakfast. During the night, both Pyron and Chivington had sent small parties to search for their enemies. The Texans were captured by the Federal party, giving Chivington good information on his foe’s location. Despite the lack of reconnaissance, Pyron decided to continue slowly east in search of the Union force without attempting to join or contact the main Confederate column camped 12 miles to the south. He had approximately 420 men with whom to oppose Chivington – his own 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles battalion, a four-company battalion of the 5th Texas Mounted Volunteers, three small companies of locally recruited “irregulars,” including the Brigands, as well as the artillery support of two six-pounder guns.

Chivington was also anxious to locate his foe. With approximately 404 men of his advance party, he left Kozlowski’s Ranch at about 8:00 a.m., about the same time the Rebels started. His force included 170 Colorado infantrymen and 234 cavalry troopers from the regular squadron and from Co. F, 1st Colorado, that regiment’s mounted unit. After marching five miles, the Union vanguard passed Pigeon’s Ranch, another major way station on the Santa Fe Trail, then crested Glorieta Pass and descended into the eastern reaches of Apache Canyon. At the same time, Pyron had halted less than two miles ahead, on an open, flat shelf north of Galisteo Creek. Many of the Texans who had not slept during the cold night immediately fell asleep, while their commander sent a small party of Brigands, with his two cannons, ahead to try again to locate the Federals.

They were themselves “located.” Around a sharp bend in the road came Chivington’s advance party, which immediately captured several Brigands and spread out across the Santa Fe Trail to confront the remainder, who may indeed also have been asleep. Two rounds from the accompanying artillery passed over the Federals’ heads. The cannons and Brigands retreated in haste back to their main force, now rudely awakened. In pursuit came the Union infantry and cavalry, which, at about 2:30 p.m., halted in and across the road as a Confederate battle line quickly appeared on the open shelf where the Texans had slumbered. Chivington’s infantry outflanked the Rebel line, but his cavalry failed to charge the wavering enemy, and Pyron was able to withdraw to another defensive position a mile or so immediately west of Apache Creek, an insignificant dry gully spanned by a short, wooden bridge. With his two artillery pieces near the Santa Fe Trail, and his dismounted troopers across the valley floor and up the mountainsides north and south of Galisteo Creek, the Confederate commander awaited an attack by his enemy.

This time Maj. Chivington’s tactic worked perfectly. Sending regular and volunteer soldiers around both flanks of the Texan line, he waited for those units to get into position, then sent the 1st Colorado’s Co. F galloping down the Santa Fe Trail, jumping the destroyed bridge across Apache Creek and through the center of the Rebel line. The artillery limbered up and retreated west to Pyron’s camp at Johnson’s Ranch, followed by those Texans who could run or ride. In the aftermath, the Federals captured 71 Texans, the greatest Confederate loss of the New Mexico campaign. The fighting lasted only until about 4:00 p.m., with equal losses on both sides – four or five killed and 20 wounded. At dusk, Chivington withdrew to Pigeon’s Ranch while the main Federal column approached Kozlowski’s Ranch.

During the night of March 26–27, both vanguard commanders sent word of their fight back to their main columns. Both Lt. Col. Scurry and Col. Slough hurried to concentrate their forces for renewed battle the next day. No attack came, so the Texans fortified their Johnson’s Ranch camp with earthen embankments while the Federals continued their concentration at Kozlowski’s Ranch.

On the morning of March 28, Scurry left one cannon and a handful of men to guard his supplies and field hospital, hoping that with the bulk of his force he could defeat his enemy and continue on to Fort Union and its vital supplies. He had about 1,300 troops available, including nine of the 10 companies of the 4th Texas, marching as infantry since the Battle of Valverde, elements of the 5th and 7th Texas and a company-sized force formed from a portion of Pyron’s 2nd Texas battalion and other “irregular” units. Two 12-pounder field howitzers and a six-pounder gun provided artillery support for the Confederate column.

Slough’s federal force was almost identical in number. All ten 1st Colorado companies were available, along with a regular infantry battalion and cavalry squadron. In addition, both Ritter’s heavy battery of field howitzers and guns and Claflin’s light battery of mountain howitzers strengthened the Federal force. Perhaps unwisely, the Union supply train accompanied the troops.

Shortly before 9:00 a.m. Slough broke camp and marched west along the Santa Fe Trail, intending to “obstruct the movement of and cut off the supplies of” the Confederate force threatening Fort Union. His tactical plan was, however, more complex. He directed Chivington to take a 500-man party of regular and volunteer infantry across Glorieta Mesa, south of the Santa Fe Trail, and march west to a point above Johnson’s Ranch, where he anticipated the Texan camp. Meanwhile Slough would lead the remaining 800 soldiers along the road, confronting the Rebels in their camp while Chivington descended on the Texan flank in a coordinated attack. It was a standard Napoleonic plan dependent on Scurry’s force being still encamped at Johnson’s Ranch. It wasn’t.

Instead, as Chivington’s flanking party left the road and the main column paused to further organize at Pigeon’s Ranch, the advance pickets of each force encountered one another along the Santa Fe Trail, bringing on, about 11:00 a.m., the key battle of the Civil War in New Mexico. The Confederate foot soldiers, followed by dismounted horsemen and artillery, quickly deployed and unlimbered in and across the road and pushed back a small Union artillery and cavalry force sent ahead of the main force. Slough and his second-in-command Lt. Col. Tappan responded by strengthening the center of a new Union defensive line with their eight cannons and sending cavalry, as well as the available 1st Colorado companies, to support the artillery and form a reasonably strong line parallel to that being extended south of the road by the Confederates. The opponents opened a furious fire in these positions for some three hours. The Texans, outnumbering the Federals by about 1,300 to 800, gradually outflanked the Union line.

Realizing the strength of his foe, Col. Slough dispatched a messenger to find Chivington’s flanking party. He also withdrew from the positions west of Pigeon’s Ranch and formed a new defensive line north and south of the road through the ranch buildings and corrals, with artillery forming the center of this new, strong line. Scurry also used this time to reorganize his force, planning a coordinated, three-pronged assault on the new Federal line. By 2:00 p.m. he attacked; the southern and northern flanking parties failed to break the Union lines, however, and Scurry himself led two ferocious assaults down the center, both blown apart by the concentrated Federal artillery and infantry fire. Finally, almost two hours later, Maj. Pyron, leading the Confederate left flanking party succeeded, and a third charge against the enemy center also succeeded, causing Slough to abandon the positions around Pigeon’s Ranch and fall back down the Santa Fe Trail to a final defensive line across that road. The Rebels followed, but darkness and exhaustion brought an end to the Battle of Glorieta, along with terrible news for the Texans.

While fighting raged around Pigeon’s Ranch, Maj. Chivington’s flanking party, knowing nothing of that conflict, descended on the Confederate camp, spiked the cannon left in its defense, captured and paroled any Texan soldiers present, then burned the 80 wagons containing everything the Confederates needed to continue the fight in New Mexico. Chivington’s men returned to their companions late in the night, having won their part of the Battle of Glorieta and the Civil War in the Far West.

The Confederates retreated to Santa Fe to recover their strength and replace their supplies, and plan another advance on Fort Union. They were unsuccessful and soon began an extended and epic withdrawal from the frontier territory they had thought would be easy to conquer and occupy.

The Battle of Glorieta could then be seen as a clear Union tactical and strategic victory. Although the fighting around Pigeon’s Ranch was a draw, the Texans having gained two miles of Santa Fe Trail while taking almost identical casualties as their foe (some 48 killed and 60 wounded), the destruction of the Rebels’ supply train was an obvious and conclusive Union success.

Colonel Slough’s strategic goal had been met; he had stopped the Confederate advance on Fort Union. The Rebels soon retreated back to Texas, never to return, and the Battle of Glorieta truly represented the high-water mark of the Confederate invasion of Federal territory in the Far West, and, in that context, although much smaller than the more famous eastern battle fought a year later, it can easily be seen as the Gettysburg of the West.