The American Civil War was a formative experience for the many Americans who lived through it. Hardly anyone escaped being touched by the war in some form or another. Hispanic Americans were no exception; just as it did for so many other groups, the war tore apart Hispanic communities, saw young Hispanic men (and women) marching off to fight in both armies, and made heroes out of brave and gallant Hispanics.

The term Hispanic is used to refer to any person who has at least one ancestor from Spain, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central or South America. From newly arrived Spanish immigrants in New York City to Mexicans who suddenly found themselves Americans in the wake of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to wealthy Creole planters in the deep South, Hispanics both played an important role in and were shaped by the Civil War.

The Mexican-American War was one of the most significant events that pushed the nation closer to the brink of civil war. A conflict deeply rooted in imperialism and the desire to spread the “peculiar institution” of slavery westward, the conflict ended with the United States gaining a large swath of territory from the defeated Mexico: and thus, many Mexicans living in the modern states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico found themselves American citizens. In the bigger picture, this new acquisition of territory reopened past wounds about whether the newly acquired territory should be slave or free. Debates became increasingly heated and shaped around sectional, rather than party, lines, which ominously foreshadowed the coming conflict. Before and after the war, contemporaries would attribute a significant portion of the blame for the Civil War on the Mexican War; Ralph Waldo Emerson rightly predicted that “Mexico will poison us,” echoed by Ulysses S. Grant’s later assertion that the Civil War was divine punishment for the “wicked” Mexican War.

The war that came about in part because of the Mexican-American War would engulf thousands of Hispanics. Like many young men throughout the country, they had to make a choice: remain loyal to the Union or fight for the Confederacy.

Geography was a large factor in their decisions. In the Southeast, a significant number of Creoles – descendants of French or Spanish colonists – were wealthy planters with a reliance on slave labor. Hispanics throughout the Southeast, most notably Louisiana, Alabama, and Florida, would fight for the Confederacy in large numbers, numerous enough to form entire regiments. In the North, urban centers such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia were the homes of large numbers of immigrants, a significant portion of them Hispanic. Immigrants from Spain, Portugal, Cuba, Puerto Rico and Mexico struggled to be accepted by native-born Americans and viewed enlisting in the Union Army as the quickest way to become a fully integrated American citizen.

Hispanics – especially Mexican-Americans – were more divided in their loyalties in the former Mexican Cession. Hispanics from California, a free state, mostly served the Union, as did most in the New Mexico territory. Slavery was banned by the Mexican Republic in 1829 and the climate of the Southwest was unsuitable to agriculture, preventing the institution from taking hold in the region. However, some did join the Confederacy, on account of hostility to the American government or purely due to proximity to the South. The most division, however, occurred within the state of Texas. Slavery was prevalent within Texas; in fact, Mexico’s abolition of slavery in 1829 had been a key reason for their revolt. Some Tejanos (Mexican-Americans from Texas) joined Confederate home guards and militias for the primary reason of not wanting to be sent thousands of miles away to fight in unfamiliar lands. A similar reason prompted some Tejanos to join the Union, so they could defend their families and communities from a close proximity. Many Tejanos also joined the Union because of their resentment of white Texans for taking their land. The issue of slavery also affected Tejanos’ decision; some Tejanos had grown wealthy and dependent upon enslaved labor like many of their white counterparts, while some poorer Tejanos retained an anti-slavery attitude and even helped runaway slaves escape to Mexico via the Underground Railroad.

While there are general patterns to explain their reasoning, many of these decisions came down to very personal and intimate motives and desires. Many Hispanic men with remarkably similar backgrounds would find themselves on entirely different paths during the war. Some would fight close to their home, particularly in the Southwest, while some would find themselves thousands of miles away in Virginia and Pennsylvania; some would serve in a unit made entirely of other Hispanics, while others would be integrated into primarily white regiments. Some would exceed as excellent cavalrymen, while some would become decorated sailors. Union or Confederate, Hispanics had a conspicuous place within their respective army.

Hispanics, especially those from the Southeast and Texas, played an important role in the Confederacy. There were several regiments from the Southeast with large numbers of Hispanics. Almost 800 Hispanics served as part of the “European Brigade,” a home guard for the defense of New Orleans. The brigades known as the “Louisiana Tigers” included Creoles and immigrants from Spain and Latin America and served at Antietam and Gettysburg. The Alabama Spanish Guards were aptly named and consisted entirely of men from Spain, serving as a home guard for Mobile. The 55th Alabama Regiment and the 2nd Florida Regiment both had large numbers of Hispanics; the Alabamians served at major engagements in the Western Theater, while the Floridians participated in the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg. Hispanics also served aboard Confederate blockade-runners.

One of the most well-known Hispanic Confederates is Colonel Santos Benavides, the commander of the 33rd Texas Cavalry Regiment, and the highest-ranking Tejano in the Confederate army. He played a crucial role in driving off Union forces from Brownsville in 1864.

Two Hispanic women are also notable in their support of the Confederacy. Lola Sanchez, a Cuban-American from St. Augustine, was a successful Confederate spy. She eavesdropped on Union soldiers occupying her house and reported their plans for a raid on nearby Confederates; her efforts led to the capture of the Union men and a victory for the Confederates. Loreta Janeta Velazquez was born in Cuba but, according to her memoirs, took her commitment to the Confederate cause very seriously. Without her husband’s knowledge, she disguised as a Confederate soldier named Harry T. Buford and fought at notable battles such as Bull Run and Fort Donelson. Although Buford’s true identity was revealed, Velazquez didn’t give up and rejoined the army to participate in the Battle of Shiloh. Afterwards, she continued to spy for the Confederacy.

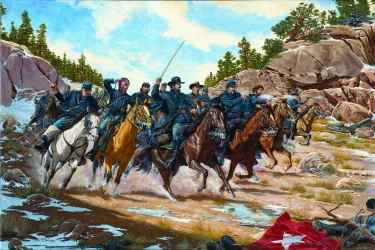

Hispanics served the Union in greater numbers. The 39th New York Volunteer Regiment, composed entirely of European immigrants and fighting in European-style uniforms, was known as the Garibaldi Guard. The “Spanish Company” of the regiment contained Spanish, Cuban, and Puerto Rican immigrants and participated in the Gettysburg, Mine Run, and Wilderness campaigns. Various other Hispanics from the North were integrated throughout other regiments. Hispanics from the Southwest made up the largest portion of Hispanics who served the Union. Californios, or Californians of Mexican descent, were already skilled on horseback, which translated to them being excellent cavalrymen. The state raised large numbers of Californio calvary units, including the 1st California Cavalry Battalion, which served in the New Mexico territory and was comprised entirely of Mexican-Americans; all of the officers even had to be fluent in Spanish. Twelve companies of Tejano cavalry were raised from Texas, despite it being a Confederate state.

The most famous of Union Hispanics is not a soldier, but a sailor; Vice Admiral David G. Farragut was the son of a Spanish captain who served in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Farragut’s most significant victories include the capture of New Orleans in 1862 and of Mobile Bay in 1864, where he supposedly uttered the legendary phrase, “Damn the torpedoes!” Argentine-born Henry Pleasants moved to the U.S. at the age of 13 and became a mining engineer in Pennsylvania coal country. This experience led him to conceive of the idea to break through Confederate fortifications at Petersburg by building a mine shaft under them and detonating an explosion of four tons of gunpowder. Although the plan was executed extremely poorly, Pleasants was promoted to brigadier general for his service at Petersburg. Luis F. Emilio, the son of a Spanish immigrant, lied about his age and enlisted at 16 years old. He was soon chosen to be an officer in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and served in the assault on Fort Wagner; Emilio became the regiment’s acting commander in the aftermath, all other officers having been killed or wounded. He served with distinction until the end of the war, mustered out when he was not yet even 21 years old. Joseph H. De Castro, the flag-bearer of the 19th Massachusetts Infantry, was the first Hispanic-American to be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in the defense of Cemetery Ridge against Pickett’s charge during the Battle of Gettysburg. De Castro attacked a Confederate flag bearer with the staff of his own colors and became one of seven men from his regiment to earn the Medal of Honor in 1864. Hispanics also served in the American navy; John Ortega, from Spain, served on the USS Saratoga and helped enforce the blockade, and Philip Bazaar of Chile participated in the assault on Fort Fisher. Both earned the Medal of Honor for their actions.

The largest amount of Hispanics served in the Southwest, due to the large concentration of Hispanics – primarily Mexican-Americans – who lived there. Although many people assume all Civil War battles occurred on the eastern half of the North American continent, fighting also occurred in the West. The New Mexico territory saw both organized battles and guerilla warfare between the Union and Confederacy.

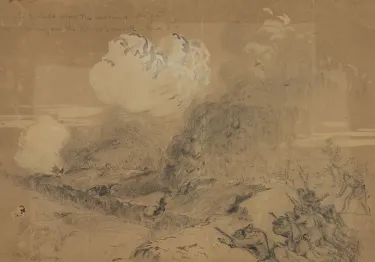

The Battle of Glorieta Pass is the most famous battle that occurred in this region. In mid-1861, Confederates invaded the New Mexico territory, interested in the gold and silver mines there, as well as hoping to unite Texas with vital California ports. Union forces at Glorieta Pass put a stop to these incursions, and for that reason, the battle is known as the Gettysburg of the West. Former Mexican militia officer Manuel Chaves led the troops responsible for destroying the Confederate supply train, thus turning the tide of the battle.

Guerilla warfare also occurred throughout the Southwest, especially in Texas. Texas saw its own civil war, where Tejanos turned upon their fellow Tejanos. Some Tejanos were asked by Union authorities to wage guerilla warfare on Confederates in the region, one of them Cecilio Balerio and his son Juan. The Balerios and their group of guerillas raided Confederate cotton trains near Corpus Christi. However, the younger Balerio was captured by Confederate officials and was forced to reveal the location of their encampment. At the last moment, Juan shouted an alarm, waking up the guerillas, and bloody fighting ensued.

Just as civilians in the proximity of fighting suffered in the main theaters of the war, Hispanic civilians in the Southwest suffered. Their crops were often destroyed, and disease was spread by the armies in the region. When men were called out to join militias, women were often the last line of defense for their communities in an increasingly lawless and dangerous land. Despite their circumstances, they showed immense resilience and strength.

The Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated by Hispanics and those in Latin America still under Spanish colonial rule. However, many Hispanics in the Southwest were locked in debt peonage. Similar to the system of sharecropping that emerged in the South after the abolition of slavery, Hispanics and other poor residents of the Southwest paid for their debts through labor. Calls for the end of this system, essentially long-term bondage, first emerged at the end of the war and culminated in the Thirteenth Amendment and the 1867 Anti-Peonage Act, though the system lingered into the next century; only availability of proper employment would cause it to disappear entirely. After Reconstruction, the Jim Crow laws that limited the rights of African Americans throughout the South also negatively affected Hispanics in the region. It wouldn’t be until the civil rights movements of the mid-20th century that Hispanics made significant gains in rights and liberties.

As the largest and bloodiest conflict on American soil, the Civil War swept up nearly everyone into the fray. Hispanics were no exception, and as a result, they were significantly impacted by the conflict and shaped the conflict in important ways.

Further Reading

- Hispanics and the Civil War By: The National Park Service

- Tejanos in Gray: Civil War Letters of Captains Joseph Rafael de la Garza and Manuel Yturri By: Jerry Thompson

- Vaqueros in Blue and Gray By: Jerry Thompson

Related Battles

147

222